Florida Tech’s Caldon Whyte is two years into a lengthy universe exploration to earn his Ph.D. in space sciences. After graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in astrobiology in 2023, he’s fascinated by white dwarf stars—the cooling remnants of low-mass stars (e.g., our sun) that have exhausted their nuclear fuel source—and the likelihood of life surviving in their orbits.

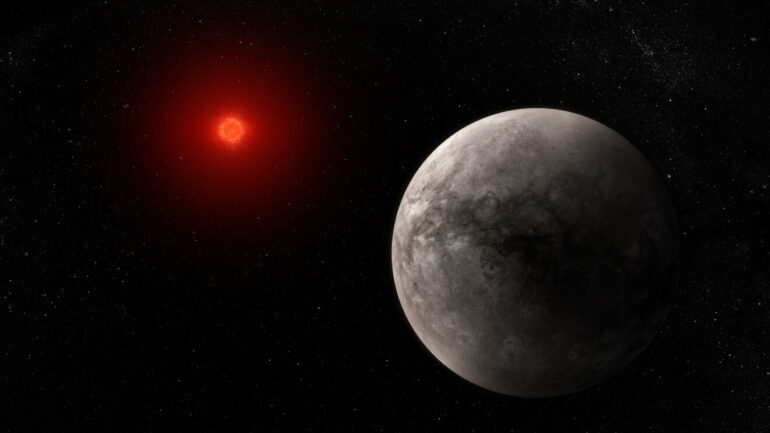

For years, researchers thought white dwarfs’ dynamic temperature decrease made their atmospheres too unstable for life. However, as the James Webb Space Telescope begins to document white dwarfs with exoplanets in their orbits, the late-stage stars are captivating researchers looking for life.

With the help of advisors Manasvi Lingam and Luis Henry Quiroga-Nuñez, Whyte developed a model assessing whether two processes, photosynthesis and ultraviolet (UV)-driven abiogenesis, would receive enough energy in a white dwarf’s habitable zone to occur.

His model found that white dwarfs can fuel both processes simultaneously. The discovery of this potential Earth-like similarity could change the trajectory of the search for life in the universe.

Whyte’s results culminated in his paper, “Potential for Life to Exist and be Detected on Earth-like Planets Orbiting White Dwarfs, ” published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. Co-authors are Lingam and Quiroga-Nuñez, as well as Paola Pinilla from the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London.

Scientists have previously established the bounds of these habitable zones, which are areas found around a star where an orbiting planet can get enough energy to potentially sustain liquid water on its surface—a prerequisite for life.

We know photosynthesis exists on Earth, and scientists have found UV-driven abiogenesis—the concept that UV radiation can help generate life from non-living matter—to be a probable theory for Earth’s origins of life.

The “Goldilocks zones,” as NASA describes them, create conditions that are neither too hot nor too cold for life—they are, as the fairytale noted, “just right.”

Earth, for example, orbits the sun at a distance that can sustain liquid water. If Earth were too far, water would freeze; if Earth were too close, water would evaporate. Habitable zones widen when stars emit more energy and narrow when that energy source decreases.

White dwarfs are unique because their temperature is inconsistent, Whyte explained. Since the late-stage stars no longer have a fuel source, they spend the remainder of their lives cooling down. Their energy outputs are inconsistent, and their habitable zones are constantly narrowing.

Whyte wanted to test viability by exploring whether the star’s energy could support photosynthesis or UV-driven abiogenesis over the 7 billion years or so that scientists have estimated is the maximum habitable lifetime of an Earth-like planet in this zone.

To do it, he developed a model that simulated an Earth-like planet orbiting a white dwarf. He modeled the orbiting Earth-like planet as the habitable zone devolved, noting how much energy it received from the cooling star over time.

Whyte found that throughout that 7-billion-year habitable period, the modeled planet received enough energy to support both processes—a rare Earth-like overlap, he said.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

“That isn’t really common around most stars,” Whyte said. “Something like [our] sun, of course, can provide enough energy, but brown dwarfs and red dwarfs smaller than the sun don’t really provide the energy in [both] the UV and the photosynthesis range.”

Whyte’s findings can help scientists make real-world decisions about future space exploration. When embarking on a search for star systems that could sustain photosynthesis, for example, astronomers can now know that white dwarfs create a potentially viable environment for some planets, thanks to Whyte’s research.

“We’re giving them the confidence that these star systems are worth investing time and money into,” he said.

This paper is just the first phase of Whyte’s doctoral research, and it serves as solid groundwork for what’s to come. Next, he plans to observe existing white dwarfs through the James Webb Space Telescope; he’s already on the search for them near our sun.

If Whyte can find a white dwarf that aligns with the model from his paper, he’ll search for a planet in its orbit. He’ll use the observational data he collects through this process to adjust his model and identify promising star systems.

While he’s not sure he’ll be able to detect a planet, he’s eager to contribute to the search for life.

“Even if we don’t detect something positive, just collecting solid results (matters), whether that’s being able to say, ‘maybe these aren’t the best targets to look at,” or finding some kind of hint or clue,” Whyte said. “Any results will be meaningful.”

More information:

Caldon T. Whyte et al, Potential for Life to Exist and be Detected on Earth-like Planets Orbiting White Dwarfs, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2024). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ad9821

Provided by

Florida Institute of Technology

Citation:

Study reveals white dwarfs could host life-supporting planets (2025, March 18)