Titan’s “magic islands” are likely floating chunks of porous, frozen organic solids, a new study finds, pivoting from previous work suggesting they were gas bubbles. The study was published in Geophysical Research Letters.

A hazy orange atmosphere 50% thicker than Earth’s and rich in methane and other carbon-based, or organic, molecules blankets Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Its surface is covered with dark dunes of organic material and seas of liquid methane and ethane. Stranger yet are what appear in radar imagery as shifting bright spots on the seas’ surfaces that can last a few hours to several weeks or more.

Scientists first spotted these ephemeral “magic islands” in 2014 with the Cassini-Huygens mission and have since been trying to figure out what they are. Previous studies suggested they could be phantom islands caused by waves or real islands made of suspended solids, floating solids, or bubbles of nitrogen gas.

Xinting Yu, a planetary scientist and lead author of the new study, wondered if a closer look at the relationship between Titan’s atmosphere, liquid lakes, and the solid materials deposited on the moon’s surface could reveal the cause of these mysterious islands.

“I wanted to investigate whether the magic islands could actually be organics floating on the surface, like pumice that can float on water here on Earth before finally sinking,” Yu said.

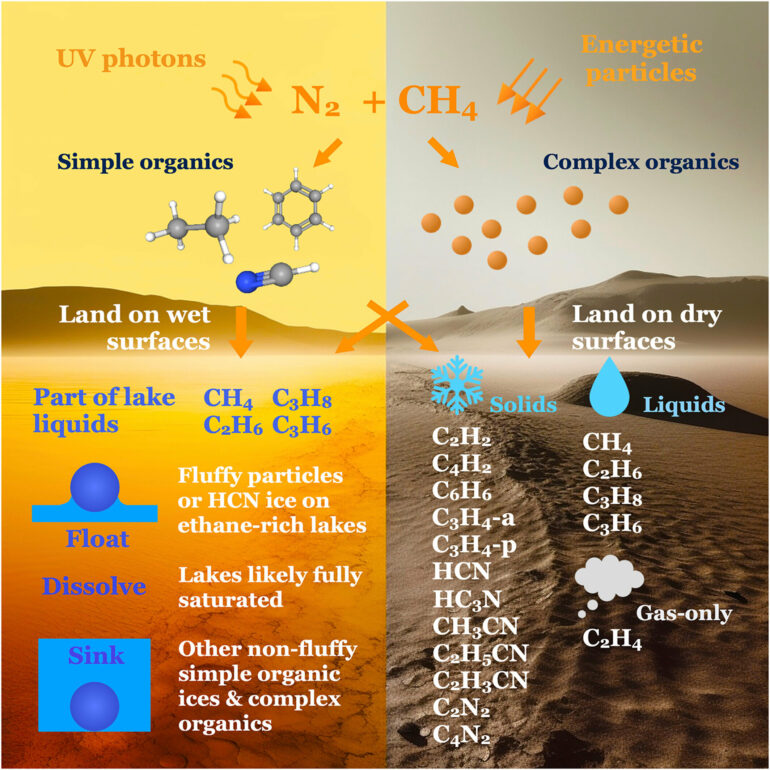

A weird world of organics

Titan’s upper atmosphere is dense with diverse organic molecules. The molecules can clump together, freeze, and fall onto the moon’s surface—including onto its eerily smooth rivers and lakes of liquid methane and ethane, with waves only a few millimeters tall.

Summary of the fate of simple and complex organics on Titan’s surface (background image AI generated by X. Yu using Midjourney). © Geophysical Research Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2023GL106156

Yu and her team were interested in the fate of these organic clumps upon reaching Titan’s hydrocarbon lakes. Would they sink or float?

To find the answer, the team first investigated whether Titan’s organic solids would simply dissolve in the moon’s methane lakes. Because the lakes are already saturated with organic particles, the team determined that the falling solids would not dissolve when they reached the liquid.

“For us to see the magic islands, they can’t just float for a second and then sink,” Yu said. “They have to float for some time, but not for forever, either.”

Titan’s lakes and seas are primarily methane and ethane, both of which have low surface tension, making it harder for solids to float. The models suggested that most of the frozen solids were too dense and the surface tension too low to create Titan’s magic islands unless the clumps were porous like Swiss cheese.

If the icy clumps were large enough and had the right ratio of holes and narrow tubes, the liquid methane could seep in slowly enough that the clumps could linger at the surface, the researchers found.

Yu’s modeling suggested individual clumps are likely too small to float by themselves. But if enough clumps massed together near the shore, larger pieces could break off and float away, similar to how glaciers calve on Earth. With a combination of a bigger size and the right porosity, these organic glaciers could explain the magic island phenomenon.

In addition to the magic islands, a thin layer of frozen solids coating Titan’s seas and lakes could explain the liquid bodies’ unusual smoothness. Thus, the findings from this study could explain two of Titan’s mysteries.

More information:

Xinting Yu et al, The Fate of Simple Organics on Titan’s Surface: A Theoretical Perspective, Geophysical Research Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2023GL106156

Provided by

American Geophysical Union

Citation:

Titan’s ‘magic islands’ are likely to be honeycombed hydrocarbon icebergs, finds study (2024, January 5)