Today, the atmosphere of our neighbor planet Venus is as hot as a pizza oven and drier than the driest desert on Earth – but it wasn’t always that way.

Billions of years ago, Venus had as much water as Earth does today. If that water was ever liquid, Venus may have once been habitable.

Over time, that water has nearly all been lost. Figuring out how, when and why Venus lost its water helps planetary scientists like me understand what makes a planet habitable — or what can make a habitable planet transform into an uninhabitable world.

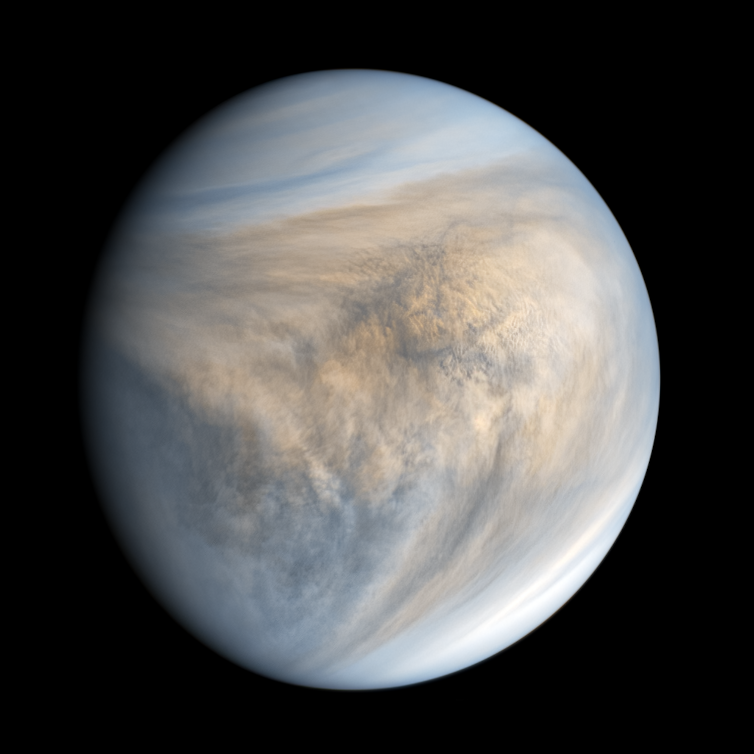

Venus, Earth’s solar system neighbor.

JAXA/ISAS/DARTS/Kevin M. Gill, CC BY

Scientists have theories explaining why most of that water disappeared, but more water has disappeared than they predicted.

In a May 2024 study, my colleagues and I revealed a new water removal process that has gone unnoticed for decades, but could explain this water loss mystery.

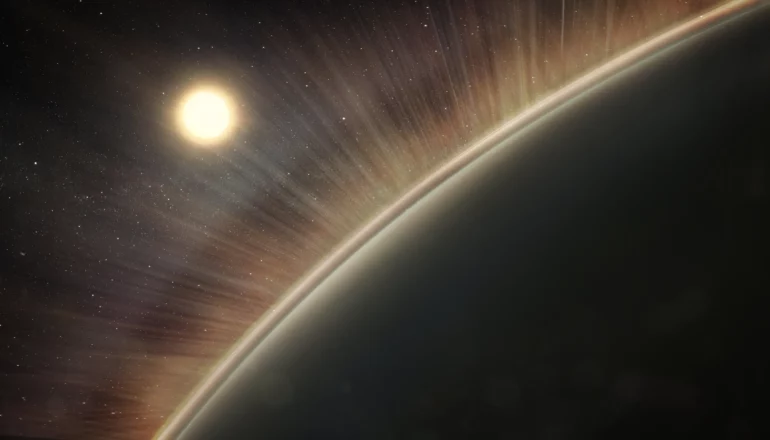

Energy balance and early loss of water

The solar system has a habitable zone – a narrow ring around the Sun in which planets can have liquid water on their surface. Earth is in the middle, Mars is outside on the too-cold side, and Venus is outside on the too-hot side. Where a planet sits on this habitability spectrum depends on how much energy the planet gets from the Sun, as well as how much energy the planet radiates away.

The theory of how most of Venus’ water loss occurred is tied to this energy balance. On early Venus, sunlight broke up water in its atmosphere into hydrogen and oxygen. Atmospheric hydrogen heats up a planet — like having too many blankets on the bed in summer.

When the planet gets too hot, it throws off the blanket: the hydrogen escapes in a flow out to space, a process called hydrodynamic escape. This process removed one of the key ingredients for water from Venus. It’s not known exactly when this process occurred, but it was likely within the first billion years or so.

Hydrodynamic escape stopped after most hydrogen was removed, but a little bit of hydrogen was left behind. It’s like dumping out a water bottle – there will still be a few drops left at the bottom. These leftover drops can’t escape in the same way. There must be some other process still at work on Venus that continues to remove hydrogen.

Little reactions can make a big difference

Our new study reveals that an overlooked chemical reaction in Venus’ atmosphere can produce enough escaping hydrogen to close the gap between the expected and observed water loss.

Here’s how it works. In the atmosphere, gaseous HCO⁺ molecules, which are made up of one atom each of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen and have a positive charge, combine with negatively charged electrons, since opposites attract.

But when the HCO⁺ and the electrons react, the HCO⁺ breaks up into a neutral carbon monoxide molecule, CO, and a hydrogen atom, H. This process energizes the hydrogen atom, which can then exceed the…