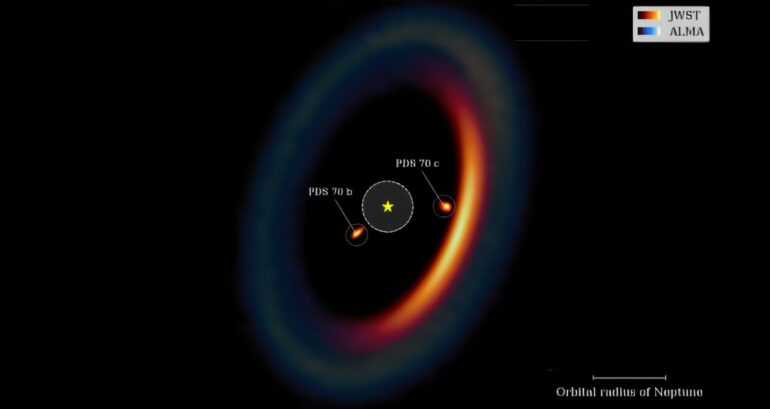

Canadian astronomers have taken an extraordinary step in understanding how planets are born, using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). JWST was used to study PDS 70, a young star with two growing planets in its orbit. This remarkable system, located 370 light-years away, gives scientists a rare chance to see how planets form and evolve during their earliest stages of development.

This new study, led by University of Victoria Ph.D. candidate Dori Blakely and an international team of researchers, used a creative approach with JWST’s unique tools to uncover details about the planets and the swirling disk of gas and dust they’re forming within. Published in The Astronomical Journal, the findings offer a fresh perspective on how planets grow over time, competing with their host stars for material.

A young star and its planetary nursery

PDS 70 is a young star, only about 5 million years old—practically a newborn compared to our 4.6-billion-year-old sun. Surrounding it is a disk of gas and dust, flattened out like a pancake, with a big gap in the middle where two planets, PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c, are taking shape. This gap is a planetary construction zone, where brand new worlds are scooping up material to grow larger.

“We’re seeing snapshots of the early stages of planetary growth, showing us what happens as worlds compete for survival in their cosmic nursery. What’s remarkable is that we can see not just the planets themselves, but the very process of their formation—they’re competing with their star and each other for the gas and dust they need to grow,” says Dori Blakely, UVic Ph.D. candidate and lead author

A new way of looking for planets with JWST

To get such a clear view of the planets and disk, the team used JWST’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) in Aperture Masking Interferometry (AMI) mode—a clever trick with the telescope. They placed a special mask with several tiny holes over the telescope, which allowed a small fraction (~15%) of the light to pass through and interfere, creating overlapping patterns, similar to the way ripples from two pebbles interact on the surface of water. By analyzing these patterns, they could ‘see’ the hidden details of the system with extraordinary precision.

“This innovative technique is like turning down the young star’s blinding spotlight so you can see the details of what’s around it—in this case, planets,” explained Prof. René Doyon, Director of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (IREx) and Principal Investigator for JWST’s NIRISS instrument.

This approach allowed the team to uncover features that traditional telescope imaging can’t detect, making this study a groundbreaking proof of concept for such observations with the powerful space-based telescope. With its ability to see details at a level never achieved before, JWST is revolutionizing the way we study planets and their origins.

“This work shows how JWST can do something completely new,” added IREx’s Dr. Loïc Albert, JWST NIRISS Instrument Scientist. “We’re using innovative techniques to look at planets in ways we’ve never done before.”

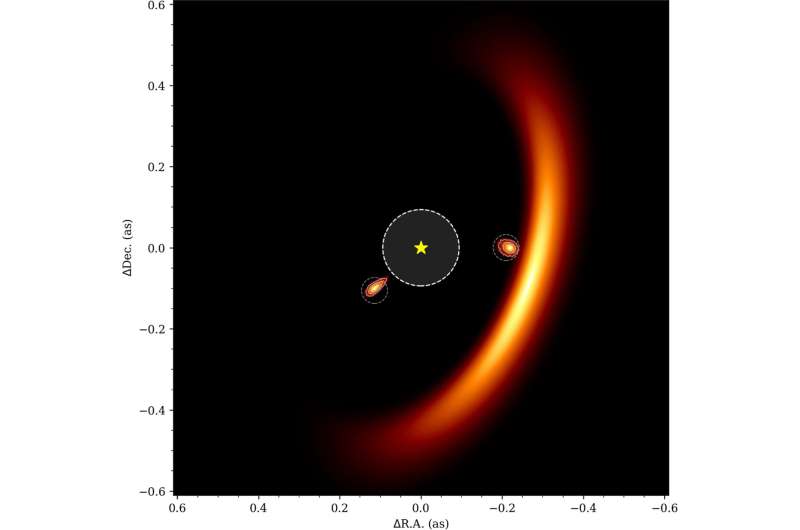

Power-law geometrical model fit to the F480M kernel phase and log kernel amplitude data of PDS 70 (images) using uniform priors on the positions of PDS 70 b and c, shown with a linear stretch in arbitrary units. With respect to the central source (yellow star), PDS 70 b is to the southeast, while PDS 70 c is directly west. The white and gray dashed contours, plotted on top of the arbitrarily colored posterior density, denote the 1σ, 2σ, and 3σ contours of the marginalized posterior of the positions of PDS 70 b and c from the Bayesian average of the posteriors of the three models. The two gray dashed circles are centered on the predicted locations of the planets at the time of the observations (J. J. Wang et al. 2021b) from whereistheplanet (J. J. Wang et al. 2021a). We mask the central region to denote the inner working angle of ~0.5λ/B = 94 mas, the diffraction limit of the data. © The Astronomical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ad9b94

Growing planets still under construction

The JWST observations confirmed the presence of two giant planets still in the process of forming. These planets are pulling in material from the disk, much like children grabbing building blocks to construct a tower. The researchers measured the planets’ light in the mid-infrared using JWST’s NIRISS instrument and determined that both planets appear to be accumulating gas—a critical phase in their development. The strong detection signatures of PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c allowed for precise measurements of their brightness and location.

These findings provide direct evidence that the planets are still growing and competing with their host star for material in the disk, supporting the idea that planets form through a process of “accretion,” gradually pulling in mass from the gas and dust around them. This rare snapshot of planets during their growth phase may help scientists understand how worlds like Jupiter and Saturn may have formed in our own solar system.

“These observations give us an incredible opportunity to witness planet formation as it happens. Seeing planets in the act of accreting material helps us answer long-standing questions about how planetary systems form and evolve. It’s like watching a solar system being built before our very eyes,” says Doug Johnstone, Principal Research Officer at the National Research Council of Canada’s (NRC) Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Hints of ‘moons-in-the-making’

The data also suggests that the planets might have rings of material around them called circumplanetary disks. These disks could be where moons are forming—like those that orbit Jupiter and Saturn today.

Previous observations of PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c at shorter wavelengths were largely explained by models originally designed for low-mass stars and brown dwarfs. However, the new JWST observations—made at the longest wavelengths ever used to study these planets—revealed extra light that could not be fully explained by these models.

This extra light hints at the presence of warm material surrounding the planets, possibly from disks of material actively accreting onto the planets. This new evidence strengthens the case for circumplanetary disks, which are believed to play a critical role in the formation of systems of moons and the growth of planets.

A step forward for planetary science

The discoveries in PDS 70 give astronomers a clearer picture of how planets and stars form and evolve together. By watching these planets grow and interact with their environment, scientists are learning how planetary systems—like our own—come to be.

“This is like seeing a family photo of our solar system when it was just a toddler,” said Blakely. “It’s incredible to think about how much we can learn from one system.”

What’s next for PDS 70?

Perhaps the most intriguing discovery was the detection of a faint, unresolved source of light within the gap of the protoplanetary disk. While the nature of this emission is unclear, it could represent a structure like a spiral arm of gas and dust, or even a third planet also forming in the system.

Follow-up observations with JWST’s other instruments, including MIRI and NIRCam, will be critical to confirm whether the glow is a new planet, a disk feature, or something entirely unexpected.

More information:

Dori Blakely et al, The James Webb Interferometer: Space-based Interferometric Detections of PDS 70 b and c at 4.8 μm, The Astronomical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ad9b94

Provided by

University of Victoria

Citation:

Witnessing the birth of planets: Webb telescope provides unprecedented view into PDS 70 system (2025, February 12)