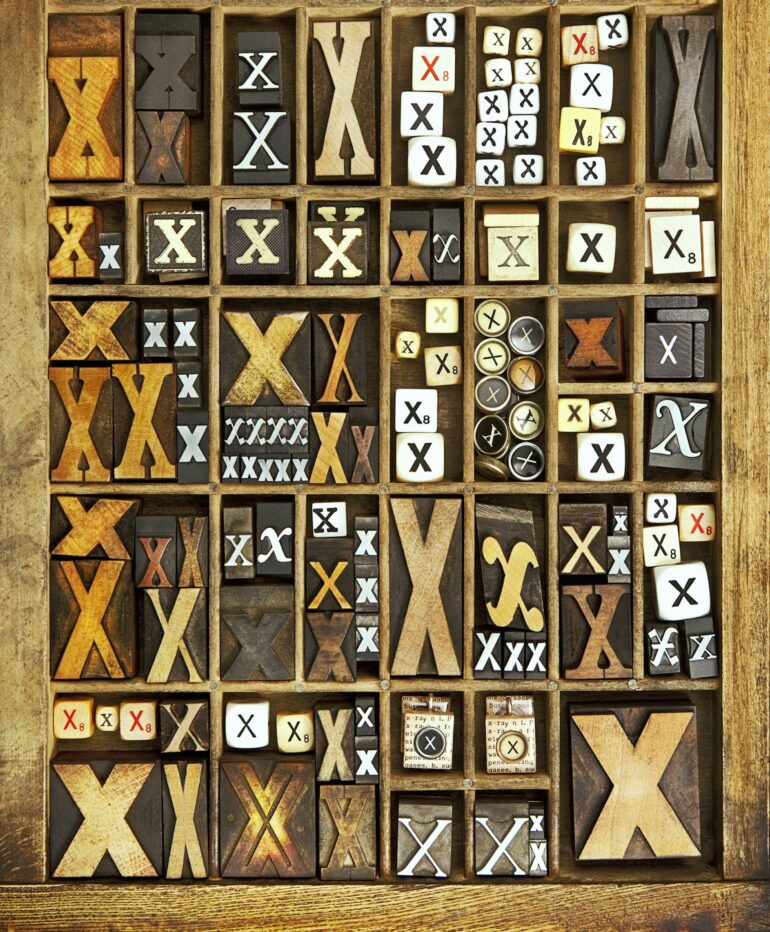

Even though x is one of the least-used letters in the English alphabet, it appears throughout American culture – from Stan Lee’s X-Men superheroes to “The X-Files” TV series. The letter x often symbolizes something unknown, with an air of mystery that can be appealing – just look at Elon Musk with SpaceX, Tesla’s Model X, and now X as a new name for Twitter.

You might be most familiar with x from math class. Many algebra problems use x as a variable, to stand in for an unknown quantity. But why is x the letter chosen for this role? When and where did this convention begin?

There are a few different explanations that math enthusiasts have put forward – some citing translation, others pointing to a more typographic origin. Each theory has some merit, but historians of mathematics, like me, know that it’s difficult to say for sure how x got its role in modern algebra.

Ancient unknowns

Algebra today is a branch of math in which abstract symbols are manipulated, using arithmetic, to solve different kinds of equations. But many ancient societies had well-developed mathematical systems and knowledge with no symbolic notation.

All ancient algebra was rhetorical. Mathematical problems and solutions were completely written out in words as part of a little story, much like the word problems you might see in elementary school.

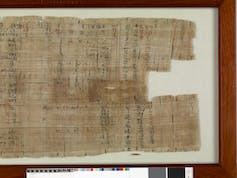

A portion of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, dated circa 1650 B.C.E.

The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

Ancient Egyptian mathematicians, who are perhaps best known for their geometric advances, were skilled in solving simple algebraic problems. In the Rhind papyrus, the scribe Ahmes uses the hieroglyphics referred to as “aha” to denote the unknown quantity in his algebraic problems. For example, problem 24 asks for the value of aha if aha plus one-seventh of aha equals 19. “Aha” means something like “mass” or “heap.”

The ancient Babylonians of Mesopotamia used many different words for unknowns in their algebraic system – typically words meaning length, width, area or volume, even if the problem itself was not geometric in nature. One ancient problem involved two unknowns termed the “first silver thing” and the “second silver thing.”

Mathematical know-how developed somewhat independently in many lands and in many languages. Limitations in communication prevented any immediate standardization of notation. However, over time some abbreviations crept in.

In a transitional syncopated phase, authors used some symbolic notation, but algebraic ideas were still presented mainly rhetorically. Diophantus of Alexandria used a syncopated algebra in his great work Arithmetica. He called the unknown “arithmos” and used an archaic Greek letter similar to s for the unknown.

Indian mathematicians made additional algebraic discoveries and developed what are essentially the modern symbols for each of the decimal digits. One especially…