China’s Zhurong rover was equipped with a ground-penetrating radar system, allowing it to peer beneath Mars’s surface. Researchers have announced new results from the scans of Zhurong’s landing site in Utopia Planitia, saying they identified irregular polygonal wedges located at a depth of about 35 meters all along the robot’s journey.

The objects measure from centimeters to tens of meters across. The scientists believe the buried polygons resulted from freeze-thaw cycles on Mars billions of years ago, but they could also be volcanic, from cooling lava flows.

The Zhurong rover landed on Mars on May 15, 2021, making China the second country ever to successfully land a rover on Mars. The cute rover, named after a Chinese god of fire, explored its landing site, sent back pictures—including a selfie with its lander, taken by a remote camera—studied the topography of Mars, and conducted measurements with its ground penetrating radar (GPR) instrument.

Zhurong had a primary mission lifetime of three Earth months but it operated successfully for just over one Earth year before entering a planned hibernation. However, the rover has not been heard from since May of 2022.

Researchers from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics under the Chinese Academy of Sciences who worked with Zhurong’s data said the GPR provides an important complement to orbital radar explorations from missions such as ESA’s Mars Express and China’s own Tianwen-1 orbiter. They said in-situ GPR surveying can provide critical local details of shallow structures and composition within approximately 100-meter depths along the rover’s traverse.

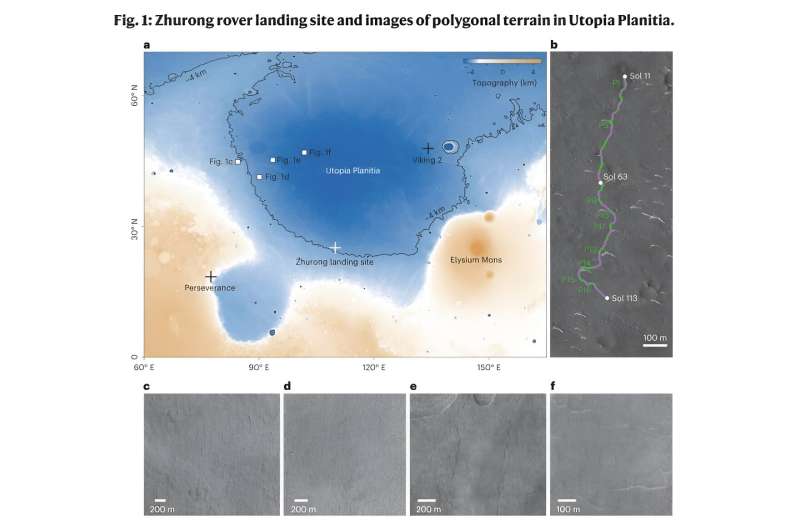

Utopia Planitia is a large plain within Utopia, the largest recognized impact basin on Mars (also in the solar system) with an estimated diameter of 3,300 km. In total, the rover traveled 1,921 meters during its lifetime.

a, Topographic map of Utopia Planitia, showing the landing sites of the Zhurong rover, the Viking 2 lander and the Perseverance rover. The ?4?km elevation contour is shown. Four local regions (c–f) with polygonal terrain are marked with white squares. b, The Zhurong rover traverse from Sol 11 through Sol 113 (HiRISE image: ESP_073225_2055). Green segments denote the wedges of buried polygons recognized from Fig. 2 (P1–P16). Purple segments denote the interiors of the polygons. c–f, Four representative HiRISE images of polygons in Utopia Planitia whose locations are marked in a: PSP_002202_2250 (c), PSP_006962_2215 (d), PSP_002162_2260 (e) and PSP_003177_2275 (f). Note the range of spatial scales for the sizes of the polygons. The average diameters of polygons shown in c–f are calculated in Extended Data Fig. 6. © HiRISE images: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona.

The researchers, led by Lei Zhang, wrote in their paper published in Nature Astronomy, that the rover’s radar detected sixteen polygonal wedges within about 1.2 kilometers distance, which suggests a wide distribution of similar terrain under Utopia Planitia.

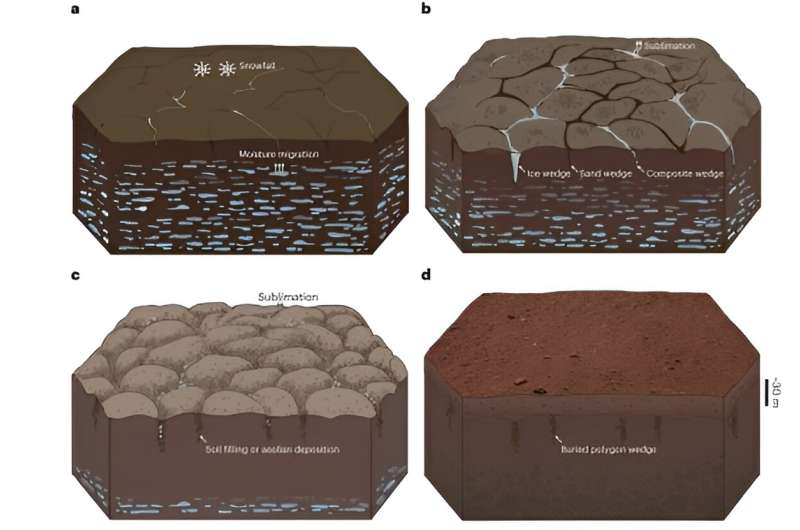

These detected features probably formed 3.7–2.9 billion years ago during the Late Hesperian–Early Amazonian epochs on Mars, “possibly with the cessation of an ancient wet environment. The paleo-polygonal terrain, either with or without being eroded, was subsequently buried” by later geological processes.

While polygon-type terrain has been seen across several areas of Mars from many previous missions, this is the first time there have been indications of buried polygon features.

The buried polygonal terrain requires a cold environment, the researchers wrote, that might be related to water/ice freeze–thaw processes in southern Utopia Planitia on early Mars.

“The possible presence of water and ice required for the freeze–thaw process in the wedges may have come from cryogenic suction-induced moisture migration from an underground aquifer on Mars, snowfall from the air or vapor diffusion for pore ice deposition,” the paper explains.

Schematic model of the polygonal terrain formation process at the Zhurong landing site. a, The origination of thermal contraction cracking on the surface. b, The formation of cracks infilled by water ice or soil material, causing three types of polygonal terrain (ice-wedge, composite-wedge and sand-wedge polygons). c, The stabilization of the surface polygonal terrain in the Late Hesperian–Early Amazonian, possibly with the cessation of an ancient wet environment. d, The palaeo-polygonal terrain, either with or without being eroded, was subsequently buried by deposition of the covering materials in the Amazonian. The Mars surface image was acquired by the Navigation and Terrain Camera (NaTeCam). © Zhang et al, from Nature Astronomy (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-023-02117-3

Earlier research from Zhurong’s radar data indicated that multiple floods during that same time frame created several layers beneath the surface of Utopia Planitia.

While the new paper indicates that the most likely possible formation mechanisms would be soil contraction from wet sediments that dried, producing mud-cracks, however, contraction from cooling lava could have also produced thermal contraction cracking.

Either way, they note that a huge change in Mars’ climate was responsible for the polygon’s formation.

“The subsurface structure with the covering materials overlying the buried paleo-polygonal terrain suggests that there was a notable paleoclimatic transformation some time thereafter,” the researchers wrote. “The contrast above and below about-35-meter depth represented a notable transformation of water activity or thermal conditions in ancient Martian time, implying that there was a climatic upheaval at low-to-mid latitudes.”

More information:

Lei Zhang et al, Buried palaeo-polygonal terrain detected underneath Utopia Planitia on Mars by the Zhurong radar, Nature Astronomy (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-023-02117-3

Citation:

Zhurong rover detects mysterious polygons beneath the surface of Mars (2023, November 30)