American Amara Majeed was accused of terrorism by the Sri Lankan police in 2019. Robert Williams was arrested outside his house in Detroit and detained in jail for 18 hours for allegedly stealing watches in 2020. Randal Reid spent six days in jail in 2022 for supposedly using stolen credit cards in a state he’d never even visited.

In all three cases, the authorities had the wrong people. In all three, it was face recognition technology that told them they were right. Law enforcement officers in many U.S. states are not required to reveal that they used face recognition technology to identify suspects.

Face recognition technology is the latest and most sophisticated version of biometric surveillance: using unique physical characteristics to identify individual people. It stands in a long line of technologies – from the fingerprint to the passport photo to iris scans – designed to monitor people and determine who has the right to move freely within and across borders and boundaries.

In my book, “Do I Know You? From Face Blindness to Super Recognition,” I explore how the story of face surveillance lies not just in the history of computing but in the history of medicine, of race, of psychology and neuroscience, and in the health humanities and politics.

Viewed as a part of the long history of people-tracking, face recognition techology’s incursions into privacy and limitations on free movement are carrying out exactly what biometric surveillance was always meant to do.

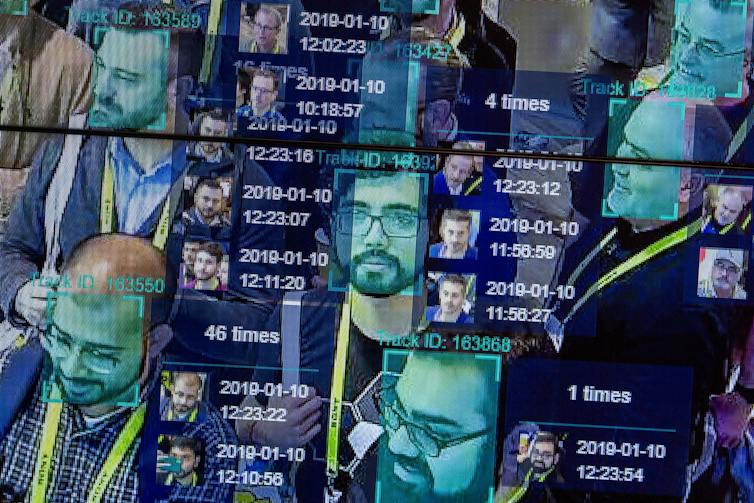

The system works by converting captured faces – either static from photographs or moving from video – into a series of unique data points, which it then compares against the data points drawn from images of faces already in the system. As face recognition technology improves in accuracy and speed, its effectiveness as a means of surveillance becomes ever more pronounced.

Paired with AI, face recognition technology scans the crowd at a conference.

David McNew/AFP via Getty Images

Accuracy improves, but biases persist

Surveillance is predicated on the idea that people need to be tracked and their movements limited and controlled in a trade-off between privacy and security. The assumption that less privacy leads to more security is built in.

That may be the case for some, but not for the people disproportionately targeted by face recognition technology. Surveillance has always been designed to identify the people whom those in power wish to most closely track.

On a global scale, there are caste cameras in India, face surveillance of Uyghurs in China and even attendance surveillance in U.S. schools, often with low-income and majority-Black populations. Some people are tracked more closely than others.

In addition, the cases of Amara Majeed, Robert Williams and Randal Reid aren’t anomalies. As of 2019, face recognition technology misidentified Black and Asian people at up to 100 times the rate of white people,…