An online game developed by a team of social psychologists could be a useful tool in the fight against misinformation, helping internet users spot misinformation and call it out for what it is: manipulative.

Misinformation – often spread by automated bots, but also unsuspecting people – worms its way into our heads by appealing to a sense of injustice or distrust and by using emotionally charged language to stoke fear and anger among social media users.

And sadly, as we’ve seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, it can have very real and sometimes lethal consequences.

But just like a vaccine stimulates an immune response to protect against disease, this new game – called GoViral! – aims to give people a taste of the tactics used to spread misinformation and conspiracy theories, so they can combat falsehoods online.

“COVID-19 falsehoods and conspiracies pose a real threat to vaccination programs in almost every nation,” says social psychologist and co-author Jon Roozenbeek.

“Every weapon in our arsenal should be used to fight the fake news that poses a threat to herd immunity.”

In two studies, players of the game were more likely to rate misinformation as manipulative, compared to genuine news, after just 5 minutes of game time. They also had more confidence in their ability to spot misinformation, even one week later, and said they were less likely to spread misinformation with others.

The game hinges on the idea that it might be more effective to stop misinformation from spreading than counter each specific falsehood with factual content from reputable sources after the misinformation has been posted online.

“While fact-checking is vital work, it can come too late. Trying to debunk misinformation after it spreads is often a difficult if not impossible task,” University of Cambridge social psychologist Sander van der Linden explains.

Instead, GoViral! is designed to prevent false narratives from taking root in the first place by building people’s confidence and ability to recognize misinformation when they see it.

“By pre-emptively exposing people to a microdose of the methods used to disseminate fake news, we can help them identify and ignore it in the future,” van der Linden says.

The worry is, as research shows, that few adults actually know how to identify misinformation – with less than half of Australian adults in one survey reporting they could confidently do so. Other studies have also shown that the inaction of silent bystanders helps fake news spread.

“The aim of countering misinformation is not to change the opinions of the people posting it, but to reduce misperceptions among the often-silent audience,” says biomedical informatics researcher Adam Dunn at the University of Sydney, who was not involved in the study.

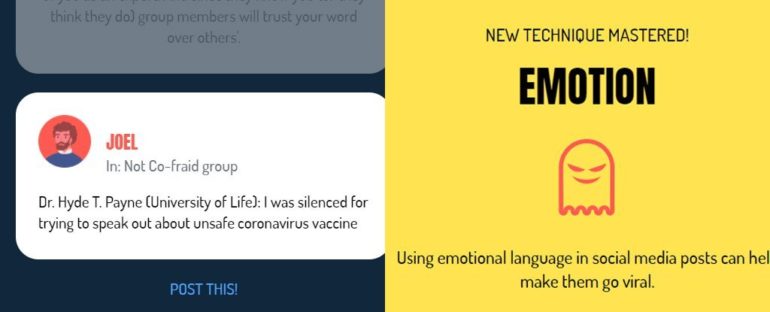

So how does the game work? Players are tasked with promoting noxious posts about COVID-19 to create public panic in a virtual game scenario using deceptive techniques, such as citing fraudulent ‘experts’.

This creates awareness amongst players of how misinformation works and how people can help stop it – which is a kind of ‘psychological resistance’ to future falsehoods, the researchers say.

Their analysis involved a total of 3,548 players in two separate studies. The first study collected data from real-world users who were surveyed before and after they played the game and shown 18 social media posts each time. Half were credible, half were not.

Immediately after playing, these GoViral! players were better able to distinguish real news about COVID-19 from convincing conspiracies than they could before gameplay.

In the second study, the researchers compared the game to a set of infographics from UNESCO’s #ThinkBeforeSharing campaign and a control group of gamers who just played Tetris.

UNESCO infographic (Basol et al. 2021)

Roughly two-thirds of GoViral! players said they felt less likely to get duped in the future; a week later, GoViral! players still rated misinformation as more manipulative than credible news, more so than the Tetris players or infographic readers.

It’s also worth noting that the infographics did help people recognize misinformation, just not as much or for as long.

“Interestingly, our findings also show that the active inoculation of playing the game may have more longevity than passive inoculations such as reading the infographics,” Roozenbeek says.

Although the results may be encouraging, the game – which is backed by the UK Cabinet Office, WHO, and UNESCO – is not getting all that much traction online. It’s available in lots of languages but has only been played about 400,000 times since its launch last October.

But whether you’re a gamer or not, remember there are a number of ways we can stop misinformation in its tracks – if you stop and think about it.

The research was published in Big Data & Society. If you want to try the game for yourself, it’s freely available here.