As he grew up in Bogotá, Colombia, Mateo Dulce Rubio would hear a familiar news story every few days—someone had stepped on another landmine. The explosion had killed or injured them. Though the capital city was far from the country’s war-torn areas, these accidents stayed in the back of his mind.

Colombia has been embroiled in conflict with armed rebel groups for roughly six decades. The guerrilla fighters have buried thousands of landmines in rural areas, putting hundreds of thousands of people at risk of death, dismemberment and displacement. Recent efforts to remove the explosives have reduced casualties, but the reported victims increasingly have been civilians.

Dulce Rubio is now a fifth-year doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon University, where he studies public policy at the Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy and statistics at the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

According to Dulce Rubio, people in the U.S. lack awareness of the dangers of landmines in countries like Colombia. “It mostly affects third-world countries, developing countries. But in those countries, it’s a very, very important problem,” he said.

That’s why, about three years ago, Dulce Rubio began leading a team of classmates and faculty in developing a three-pronged system for more accurately identifying landmine contamination. They’ve since collaborated with the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) to refine the system, called RELand. A humanitarian organization in Colombia has been field testing it in two municipalities for more than a year.

These organizations have had limited resources to understand where landmines are located; RELand uses artificial intelligence to provide more accurate predictions. So far, Dulce Rubio and several faculty members believe the results from the system’s field test are promising. The ACM Journal on Computing and Sustainable Societies has published the research team’s paper on RELand, and UNMAS plans to test it in other war-torn territories.

Rory Collins, global information management and analytics advisor at the UN’s Office for Project Services, wrote in a statement that artificial intelligence has helped the organization more efficiently remove landmines in Colombia and made its employees safer.

Scoping the problem

Landmines and other explosive remnants of war killed or wounded at least 4,710 people in at least 49 countries in 2022, according to a recent report from the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, with which the Colombian campaign is affiliated. Ukraine reported 608 casualties. Afghanistan documented 303. Colombia recorded 145.

Humanitarian organizations are working to remove landmines from these countries, but the explosives can be hard to find. Funding for the work is also limited, meaning the organizations often need to decide which contaminated areas to prioritize. Typically, they estimate where hazard areas are located by first surveying residents and analyzing historical landmine data.

Dulce Rubio and the rest of the research team believe the RELand system, if replicated, can improve that process.

“There is a lot of uncertainty on where to deploy teams, where to deploy equipment, and that’s affecting both the operational results, but also the funding,” he continued. “They spend most of it just going to places where they’re unsure if the area is actually contaminated.”

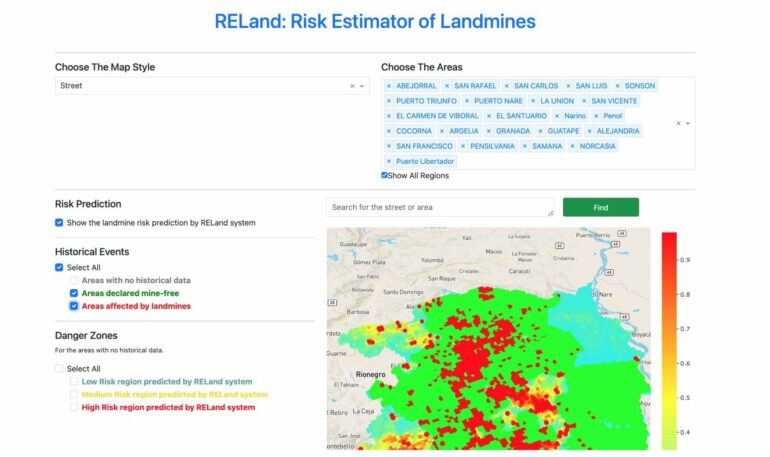

The core component of RELand is a computer program that uses machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence, to estimate the risk that landmines pose to an area. Another component is a dataset, on which the computer program is trained to make its decisions. The dataset includes geographic information, sociodemographic variables and indicators that war remnants exist.

The final component is an interactive web interface that presents the computer program’s findings.

The Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, the humanitarian organization that’s been testing RELand, first deployed the system in late summer 2023. By the end of that year, the organization had uncovered three landmines in a region RELand predicted to have many. In the other region, predicted to have few landmines, the organization had found none.

As of May 2024, no other landmines have been found in either area.

Dulce Rubio sought advice on his approach to the research from Alexandra Hiniker, the director of CMU’s Sustainability Initiative. Hiniker spent years in Cambodia, Laos and Lebanon working to ban landmines and cluster munitions, and she said RELand could help humanitarian organizations make better decisions about where to focus their time and resources.

The clearing of landmines ensures that communities can build infrastructure, children can safely play outside, and residents can live full lives, Hiniker said.

How RELand reached Colombia

Dulce Rubio wasn’t planning on researching landmines in his doctoral program –– until his second year, when he took a course on “Artificial Intelligence Methods for Social Good.” He worked with two other students to propose a solution to a societal problem using artificial intelligence.

By the semester’s end, Dulce Rubio and the other students had developed an initial framework for RELand and had gathered some encouraging results. The students wanted to continue their research, so their professor, Fei Fang, agreed to remain as an adviser. Fang, an associate professor of software and societal systems in the School of Computer Science, has met with them at least twice a month over the last year.

Hoda Heidari, Rayid Ghani and Silvia Borzutzky, professors from Heinz College and the School of Computer Science, have also collaborated with the students or provided feedback on their work.

Fang encouraged Dulce Rubio to present the team’s early findings to a humanitarian organization in Colombia, as she believed their feedback would be valuable. Eventually, Dulce Rubio connected with a UNMAS employee who has since helped the team account for geographic constraints and underreporting, among other issues.

After several conversations with Dulce Rubio, the service put him in touch with Colombian humanitarian organizations that the government has approved landmine removal operations. Dulce Rubio presented RELand to the Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, and the members of the organization agreed to test the system.

Under Colombian law, people from the affected communities must perform the operations, a requirement partly intended to employ residents. Dulce Rubio flew to Colombia in May 2023 to train them on RELand, and they began to deploy the system that August. He’s remained in touch with the organization, which will continue to test RELand for another year.

Hiniker said she values Dulce Rubio’s continued engagement with people and organizations directly impacted by this issue.

“The people directly affected are the people who know the issue best, the ins-and-outs of how it’s actually happening on the ground,” Hiniker said. “If you don’t take into account the reality on the ground, you could actually cause harm.”

What comes next

Siqi Zeng, who designed the algorithm for RELand as an undergraduate majoring in mathematics, said the project taught her about collaboration and solidified her interest in developing trustworthy artificial intelligence models. She graduated from CMU in 2023 and is now in the computer science doctoral program at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

“We worked on this system for quite a long time, so we faced a lot of challenges that we didn’t expect at the beginning,” Zeng said. “I learned a lot about the challenges of deploying artificial intelligence algorithms in practice.”

The research team’s work was named a finalist in an INFORMS competition that aims to highlight the most exciting student work that has spurred tangible change. Dulce Rubio was also invited to a session, led by the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining, about using artificial intelligence for mine action.

Dulce Rubio believes RELand can help countries impacted by war and civil strife. The lack of access to land has contributed to the armed conflicts in Colombia, he said, and that problem has only continued because land remains contaminated with explosives.

“Being able to reclaim these lands as part of their territories and their lives,” he said, “is actually a thing that can fuel more long-lasting, stable peace.”

More information:

Mateo Dulce Rubio et al, RELand: Risk Estimation of Landmines via Interpretable Invariant Risk Minimization, ACM Journal on Computing and Sustainable Societies (2024). DOI: 10.1145/3648437. On arXiv: arxiv.org/abs/2311.03115

Provided by

Carnegie Mellon University

Citation:

Each year, landmines kill residents of war-torn countries. This innovative tool could save lives (2024, October 3)