A new insight into how leaves transform into slippery layers on railway lines, causing delays for passengers and costing the rail industry millions of pounds every year, has been revealed by engineers at the University of Sheffield.

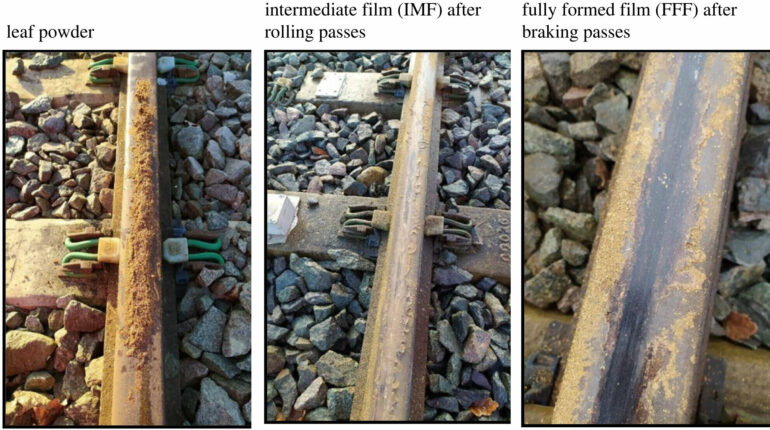

The research, led by Dr. Joe Lanigan from the University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, has revealed the chemical mechanisms that take place when leaves on the line are crushed between the wheels of a train and the railhead, forming slippery layers that make it difficult for trains to start and stop.

Findings from the study could be used to develop more effective solutions to the long-running problem that affects rail travel every autumn and winter.

Leaves on train tracks have long caused chaos for both commuters and rail companies, often leading to significant, costly delays. The problem arises when leaves are crushed against the tracks, forming a layer that dramatically reduces the friction between the train wheels and the rails, a situation described by Network Rail as the “black ice of the railway.”

In the study, “Pressure induced transformation of biomass to a highly durable, low friction film on steel” published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, researchers from the Universities of Sheffield and York have focused on the friction and chemical aspects of leaves on the line, which provides a new, detailed understanding of the processes that happen when leaves are present between train wheels and the rails.

The analysis reveals that certain chemicals, like polyphenols, including tannins (the chemicals present in wine and tea), play a crucial role in forming a strong, thin film on these surfaces. Under high pressures and heat, this film contains compounds that stick to the metal surface of the railhead.

This new understanding of the leaf-derived layer’s composition is expected to guide the development of innovative solutions to the issue.

Since phenolics play a crucial role, remediation efforts targeting these molecules, such as enzymatic digestion or using next generation cleaning agents that effectively dissolve aromatic species, should be explored, according to the study’s findings. The potential for cleaning agents to be used as tools for restoring friction to safe levels could ultimately enhance the operational performance and safety of rail transport for both passengers and operators.

Dr. Joe Lanigan from the University of Sheffield’s Department of Mechanical Engineering said, “The purpose of the research was to find out how tree leaves transform into the low friction black layer that is a problem for railways. The biology team at the University of York analyzed them from that perspective and here at Sheffield, we looked at the friction and other surface effects.

“The future goal is to use enzymes to digest leaves around railway infrastructure as a green alternative to some of the current solutions which are energy intensive or involve cutting trees down.”

The findings will inform the next phase of the research which will allow enzymes to be tailored and tested to digest leaf layers on the track. The team at York is currently in the process of testing enzymes that can degrade these leaf-derived “black layer,” low adhesion films.

More information:

Joseph L. Lanigan et al, Pressure induced transformation of biomass to a highly durable, low friction film on steel, Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1098/rspa.2023.0450

Provided by

University of Sheffield

Citation:

Engineers reveal chemicals responsible for ‘black ice’ on railway lines (2024, February 14)