A whole generation of gripping robots has been developed using a design concept originally known from fish fins. An international research team from Biomechanics, with participation from Kiel University (CAU), led by the University of Southern Denmark (SDU), has now optimized this gripping function inspired by insects and challenged this standard in robotics. They also transferred it from hand to foot elements for the first time. This would not only allow robots to grip better with less energy, but also to walk better on uneven surfaces. The findings were published in the journal Advanced Intelligent Systems and as the cover story of the current print issue.

Good contact: Bush-cricket serves as a model

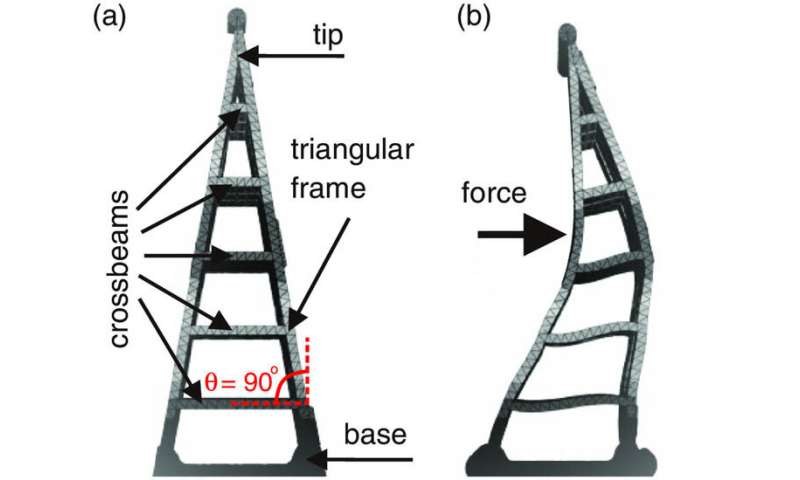

Many robots can firmly enclose target objects with their gripping elements without much pressure. The specialized smart constructions deform to conform around the surface contour of the objects. This is based on the so-called Fin-Ray effect. “It’s fascinating: If you press on one side of a sharp triangle, it doesn’t bend away from you—as you might expect—but toward you. It doesn’t give in to the direction of pressure, but bends in the direction from which the pressure is coming,” says zoology professor Stanislav Gorb of CAU, describing the phenomenon. Almost 25 years ago, the German biologist Leif Kniese observed the effect for the first time in fish fins, which adapt optimally to different flow conditions. He discovered that the reason for this was the internal structure of the tail fin.

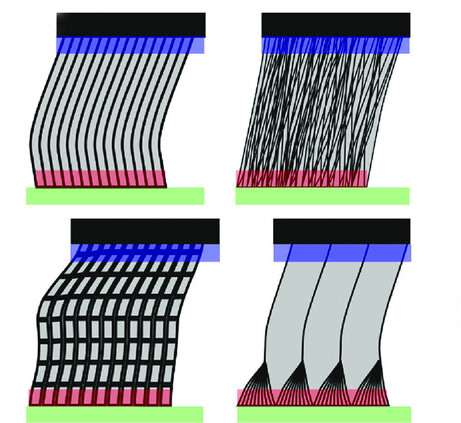

Similar crossbeams can also be found in the foot elements of many insects. They help them to adapt better to surfaces and attach themselves securely. “That’s one of our key research questions: how can insects attach so well to surfaces without using much force? How do they create the necessary contact area?” summarizes Gorb the focus of his research group “Functional Morphology and Biomechanics” at Kiel University. Together with his team from Kiel, he examined various insect feet, such as those of the bush cricket Tettigonia viridissima. While cross beams in “Fin-Ray” grippers are attached at a 90-degree angle, the angle of insects’ attachment pads was different.

For the Fin-Ray effect, detailed investigations on the effect of different crossbeam angles have not been conducted yet. The Kiel researchers have now used computer simulations to calculate the forces that would act on the gripping elements and their target objects in each case. They verified their results using experiments and force measurements with structural models from the 3D printer.

New way of producing gripping technology?

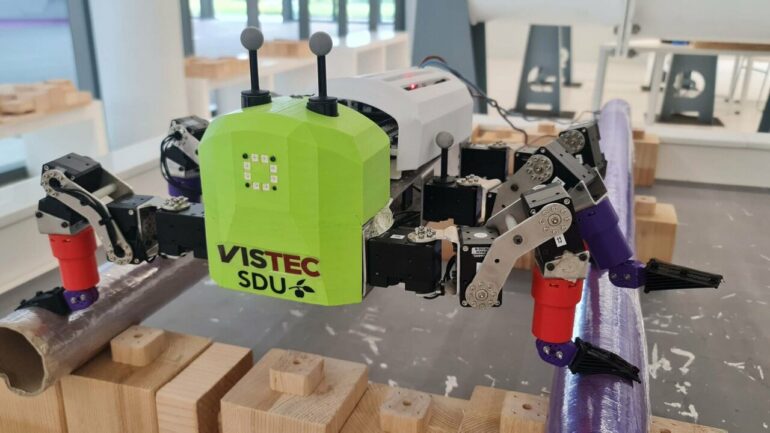

“By just changing to smaller angles, the device bends more readily around objects to provide a stronger hold that requires less force,” Gorb said. “It means that we can save up to around 20% of the robot’s energy, and take a gentler approach,” said first author Poramate Manoonpong. “We can use the gripping mechanism for a robot gripper that can handle very delicate and fragile items, like foods, and apply significantly less force or energy. It could have an impact on the way the entire industry makes robotic grippers.” Manoonpong is a professor of biorobotics from SDU and Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology (VISTEC) in Thailand. Many joint ideas already emerged a few years ago when Manoonpong spent a semester in Kiel at Gorb’s invitation as part of the Scandinavian Visiting Professorship of the CAU.

The so-called Fin-Ray® effect: If pressure is applied to the sharp triangle with the special crossbeams inside, it does not give way but curves back in the direction from which the pressure came. © Hamed Rajabi

The team from Kiel has examined the feet of the bush cricket Tettigonia viridissima in more detail: In cross-section under the scanning electron microscope, they show struts inside similar to those seen in the Fin-Ray effect. © Stanislav Gorb

Finally, the Kiel part of the research team tested what would happen if they applied this improved gripping function from the hand to the foot elements of robots. They built robot feet with internal cross beams at oriented at different angles. This allows them to bend around stones or pipes and gets a large contact area with them. Tests were conducted at SDU in Odense, Denmark, where a single robot leg platform was setup to walk on a pipe, and at VISTEC in Rayong, Thailand, where a hexapod robot was required to walk across a set of pipes o rocky terrain. Here they could see that the robot systems with an optimal angle of crossbeams at 10° used much less energy and moved faster and easier than a traditional angle of crossbeams at 90 degrees. “This something the oil and gas industry requires,” said Manoonpong.

The internal architecture of various smooth attachment pads of insects could also provide insights to improve the gripping functions of robots: The schemes show (clockwise from top right) generic fiber-like type found in most pads; foam-like type found in cicada (Auchenorrhyncha); hierarchical type found in bush crickets (Orthoptera) shown in a; thin filamentous type of honey bee (Hymenoptera). © Stanislav Gorb

Although the results are promising, this research is based on a gripper made of very soft material. The team is now facing the challenge of making a gripper that will not only bend and grip, but will also be sturdy and robust enough to handle any environment.

More information:

Poramate Manoonpong et al, Fin Ray Crossbeam Angles for Efficient Foot Design for Energy‐Efficient Robot Locomotion, Advanced Intelligent Systems (2021). DOI: 10.1002/aisy.202100133

Citation:

Insects help robots gain better grip (2022, January 27)