Sometimes when we are reading a good book, it’s like we are transported into another world and we stop paying attention to what’s around us.

Researchers at the University of Washington wondered if people enter a similar state of dissociation when surfing social media, and if that explains why users might feel out of control after spending so much time on their favorite app.

The team watched how participants interacted with a Twitter-like platform to show that some people are spacing out while they’re scrolling. Researchers also designed intervention strategies that social media platforms could use to help people retain more control over their online experiences.

The group presented the project May 3 at the CHI 2022 conference in New Orleans.

“I think people experience a lot of shame around social media use,” said lead author Amanda Baughan, a UW doctoral student in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering. “One of the things I like about this framing of ‘dissociation’ rather than ‘addiction’ is that it changes the narrative. Instead of: ‘I should be able to have more self-control,’ it’s more like, ‘We all naturally dissociate in many ways throughout our day—whether it’s daydreaming or scrolling through Instagram, we stop paying attention to what’s happening around us.'”

There are multiple types of dissociation, including trauma-based dissociation and the everyday dissociation associated with spacing out or focusing intently on a task.

Baughan first got the idea to study everyday dissociation and social media use during the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown, when people were describing how much they were getting sucked into spending time on their phones.

“Dissociation is defined by being completely absorbed in whatever it is you’re doing,” Baughan said. “But people only realize that they’ve dissociated in hindsight. So once you exit dissociation there’s sometimes this feeling of ‘How did I get here?’ It’s like when people on social media realize, ‘Oh my gosh, how did 30 minutes go by? I just meant to check one notification.'”

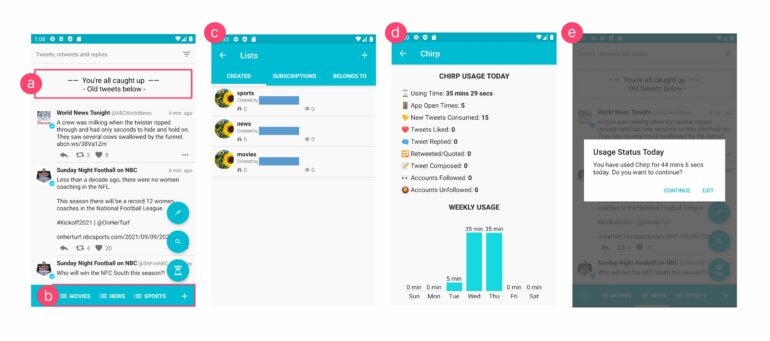

The team designed and built an app called Chirp, which was connected to participants’ Twitter accounts. Through Chirp, users’ likes and tweets appear on the real social media platform, but researchers can control people’s experience, adding new features or quick pop-up surveys.

“One of the questions we had was: What happens if we rebuild a social media platform so that it continues to offer what people like about it, but it is designed with an explicit goal of keeping the user in control of their time and attention?” said senior author Alexis Hiniker, an assistant professor in the UW Information School. “How does a user’s experience with this redesigned app compare to their experience with the status quo in digital well-being design, that is, adding an outside lockout mechanism or timer to police their usage?”

Researchers asked 43 Twitter users from across the U.S. to use Chirp for a month. For each session, after three minutes users would see a dialog box asking them to rate on a scale from one to five how much they agreed with this statement: “I am currently using Chirp without really paying attention to what I am doing.” The dialog box continued to pop up every 15 minutes.

“We used their rating as a way to measure dissociation,” Baughan said. “It captured the experience of being really absorbed and not paying attention to what’s around you, or of scrolling on your phone without paying attention to what you’re doing.”

Over the course of the month, 42% of participants (18 people) agreed or strongly agreed with that statement at least once. After the month, the researchers did in-depth interviews with 11 participants. Seven described experiencing dissociation while using Chirp.

In addition to receiving the dissociation survey while using Chirp, users experienced different intervention strategies. The researchers divided the strategies into two categories: changes within the app’s design (internal interventions) and broader changes that mimicked the lockout mechanisms and timers that are available to users now (external interventions). Over the course of the month, participants spent one week with no interventions, one week with only internal interventions, one week with only external interventions and one week with both.

When internal interventions were activated, participants got a “You’re all caught up!” message when they had seen all new tweets. People also had to organize the accounts they followed into lists.

For external interventions, participants had access to a page that displayed their activity on Chirp for the current session. A dialog box also popped up every 20 minutes asking users if they wanted to continue using Chirp.

In general, participants liked the changes to the app’s design. The “You’re all caught up!” message together with the lists allowed people to focus on what they cared about.

“One of our interview participants said that it felt safer to use Chirp when they had these interventions. Even though they use Twitter for professional purposes, they found themselves getting sucked into this rabbit hole of content,” Baughan said. “Having a stop built into a list meant that it was only going to be a few minutes of reading and then, if they wanted to really go crazy, they could read another list. But again, it’s only a few minutes. Having that bite-sized piece of content to consume was something that really resonated.”

The external interventions generated more mixed reviews.

“If people were dissociating, having a dialog box pop up helped them notice they had been scrolling mindlessly. But when they were using the app with more awareness and intention, they found that same dialog box really annoying,” Hiniker said. “In interviews, people would say that these interventions were probably good for ‘other people’ who didn’t have self-control, but they didn’t want it for themselves.”

The problem with social media platforms, the researchers said, is not that people lack the self-control needed to not get sucked in, but instead that the platforms themselves are not designed to maximize what people value.

“Taking these so-called mindless breaks can be really restorative,” Baughan said. “But social media platforms are designed to keep people scrolling. When we are in a dissociative state, we have a diminished sense of agency, which makes us more vulnerable to those designs and we lose track of time. These platforms need to create an end-of-use experience, so that people can have it fit in their day with their time-management goals.”

Additional co-authors are Mingrui “Ray” Zhang and Anastasia Schaadhardt, both UW doctoral students in the iSchool; Raveena Rao, a UW undergraduate student in the iSchool; Kai Lukoff, a UW doctoral student in the human centered design and engineering department; and Lisa Butler, an associate professor at the University of Buffalo.

More information:

Amanda Baughan et al, “I Don’t Even Remember What I Read”: How Design Influences Dissociation on Social Media, CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2022). DOI: 10.1145/3491102.3501899

Provided by

University of Washington

Citation:

‘I don’t even remember what I read’: People enter a ‘dissociative state’ when using social media (2022, May 23)