At dusk on a quiet rural road, a large animal is emerging from the forest. As the daylight fades, the moose blends in with the trees, but if a driver notices it in time, they can stop or swerve to avoid a collision. Too often, they don’t.

Each year, there are over 10,000 collisions between vehicles and wildlife in Ontario. Most are not fatal for those in the vehicle, but the costs are significant. In Canada, it is estimated that this type of collision costs about $800 million each year.

Automotive safety systems have the potential to use sensors to warn drivers of potential collisions with wildlife, vehicles and other road hazards. These systems can already warn drivers of some hazards—like a vehicle in their blind spot. But identifying unexpected hazards in dynamic road situations is a more complicated task, and new research from UTM cognitive psychologists suggests that simple safety alerts can work just as well as complicated systems that are more vulnerable to errors.

The Applied Perception and Psychophysics Laboratory (APPLY) studies visual perception and cognitive psychology, and applies it to real world problems. In a recent publication in Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, APPLY co-directors Anna Kosovicheva and Benjamin Wolfe examined ways to make vehicle safety alerts more effective.

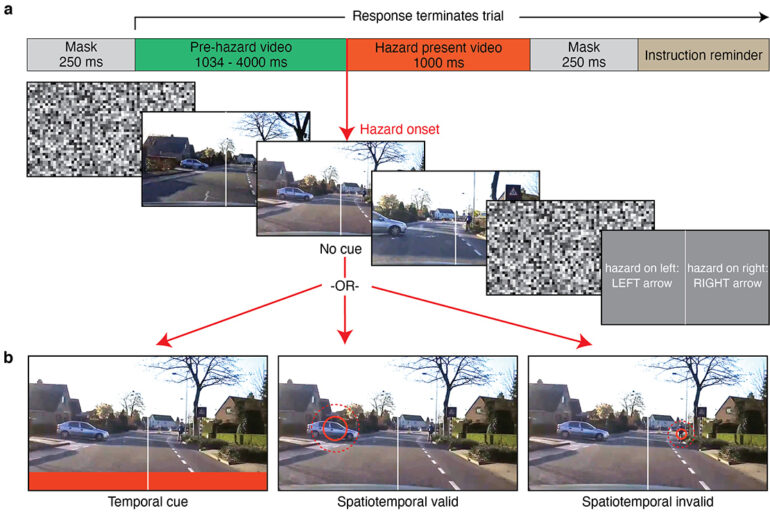

To conduct their analysis, the researchers used dashcam footage of actual driving situations they obtained from YouTube. Using methods that draw upon fundamental cognitive psychology research, they tested three different types of attentional cues that warned research participant ‘drivers’ of a looming hazard, and evaluated how each one affected their response time.

One warning drew a driver’s attention directly to the hazard. Called a spatiotemporal valid cue, this accurately superimposed a graphic of expanding red rings around the hazard itself—as though the safety system had identified the hazard in the correct place at the correct time. This worked. Driver response time was about 60 milliseconds faster.

“If you are not a vision scientist used to thinking in milliseconds, that might not sound like a lot,” says Wolfe. “But if you are driving on the highway, it could be two or three meters. That is not enough to brake fully, but could be enough to swerve and avoid a collision.”

But when a hazard was inaccurately identified, it had the opposite effect. Drivers were also given a type of warning called a spatiotemporal invalid cue. This inaccurately superimposed the set of expanding red rings around some other object in the scene. That drew the driver’s attention away from the hazard, and slowed response time by about 60 milliseconds.

“This is fairly disconcerting, from a road safety standpoint. No automated vehicle systems will ever be perfect,” says Wolfe. “The engineers building them will get it right most of the time, but sometimes systems will fail.”

Kosovicheva and Wolfe also tested a third type of cue that is simpler to execute, from an engineering standpoint. Called a temporal valid cue, drivers were warned of the presence of a hazard by a red bar at the bottom of the screen. This cue came at the right time, but it did not identify where the hazard was located. Still, it had a roughly equivalent effect to the cue that had accurately pointed to it. Response times were improved by about 60 milliseconds.

“This suggests that while complicated engineering solutions can be effective, simple alerts can be effective too,” says Kosovicheva. “Just having the information in time can be helpful, and if you are going to have a spatial component to a safety alert, the information about where a hazard is needs to be really accurate.”

More information:

Benjamin Wolfe et al, Effects of temporal and spatiotemporal cues on detection of dynamic road hazards, Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications (2021). DOI: 10.1186/s41235-021-00348-4

Provided by

University of Toronto Mississauga

Citation:

Simple vehicle safety alerts as effective as complicated warning systems (2022, January 14)