Leonardo da Vinci may have been a genius, but he was also a hot mess—at least in terms of organizing his works. When he died in 1519, the Renaissance master left behind 7,000 pages of undated drawings, scientific observations and personal journals, more or less jumbled up in a box. So, when his assistant collected da Vinci’s papers, he did his best to collate them into journals, or codices, mostly based on subject matter. Ever since, art historians have used all sorts of techniques to make an accurate timeline of the various documents now held in museums and collections across the world.

A new system developed by a University of Wisconsin–Madison engineer could help in that centuries-long effort.

William Sethares, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at UW–Madison, and Ph.D. student Elisa Ou are using a camera system and sophisticated algorithms to match the undated drawings and writings to others with established dates. And it’s not just da Vinci’s materials they’re analyzing; the two are also working on a project dating the works of Rembrandt. Further, they believe their system is applicable to any artwork or document on pre-industrial paper.

Here’s why. Prior to the middle of the 19th century, when industrial production began, paper was a handmade product. Paper makers poured a pulpy slurry onto mesh screens to produce large sheets of paper, which they then cut or folded and sold in bundles. Each of those screens was made of vertical chain wires and more delicate and numerous horizontal laid lines. Sometimes, paper makers also used fine wire to embed depictions of animals, flowers or other symbols, called watermarks, within their products.

“If you can find two pieces of paper that have the same chain lines and watermarks, then they came from the same mesh molds, and that puts them in proximity in time,” says Sethares. “That’s because these molds only lasted about six months or a year.”

Using these idiosyncratic markings to group artworks from the same batch of paper, known as mold mates, makes it possible to date the works if at least one is firmly dated.

Seeing these chain lines and watermarks with the naked eye is difficult, however—especially on delicate paper covered with ink, paint or writing by some of the world’s foremost artists. Comparing all those subtle marks in paper is also a tedious, inexact task when done by hand.

Marleen Ram, an art curator at the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands, places a drawing by Rembrandt under the watermark imaging system’s camera along with Rick Johnson, an emeritus professor of electrical engineering at Cornell University (center), and Rob Fucci, an art historian at the University of Amsterdam (right). © William Sethares

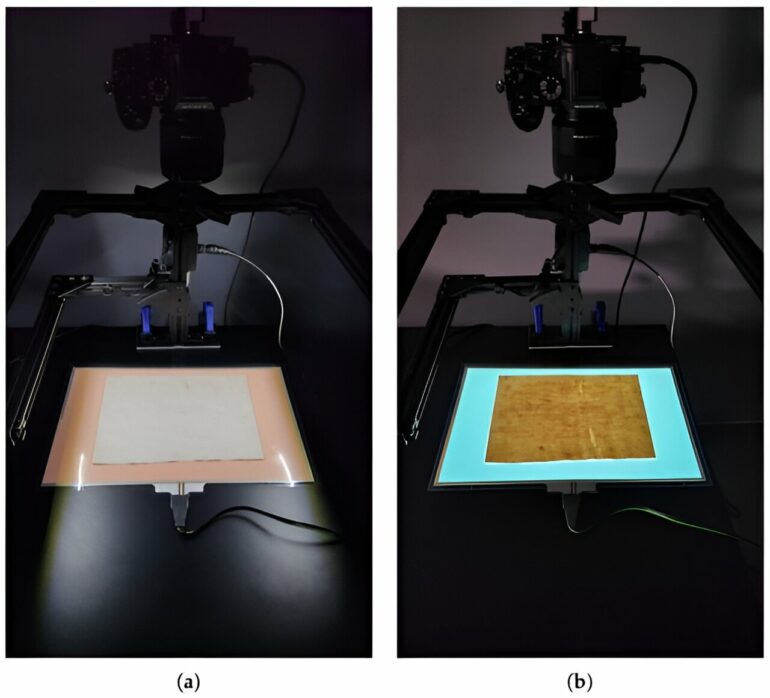

That’s why Sethares helped design and develop a hardware and software system called the watermark imaging system, or WImSy, detailed in a paper in the journal Heritage. In the system, an artwork is placed on a light plate, which backlights the paper. A camera takes several photos with light coming from different directions to capture detailed images of the artwork and the paper itself.

Next, with the assistance of algorithms, WImSy augments the photos to peer past the surface image and extract information about the paper’s internal structure, including its chain lines, laid lines and watermarks barely visible to the naked eye. Other algorithms then align and compare this internal image of the paper and any watermarks with others in a database to see if there is a match.

The team first tested the system on artworks at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The system is now being used for significant projects. In 2022, for example, art historians used it to isolate watermarks to authenticate a newly discovered drawing by the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Durer.

It’s also part of the da Vinci project, called LEOcode, which involves researchers from UW–Madison, Cornell University and the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. While Sethares has not yet had direct access to da Vinci’s journals, he has used the algorithms to examine high-resolution photos of the Codex Leicester—a collection of da Vinci’s scientific writings owned by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—to identify and catalog watermarks.

Some scholars of Rembrandt—another artist who rarely dated his artwork—are also embracing WImSy. Sethares has photographed the Dutch master’s drawings at the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, in the Netherlands; the machine is now at the Boijmans museum in Rotterdam and next goes to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Other institutions in Europe are also interested in trying out the system.

For the Rembrandt project, the team plans to photograph papers from the Dutch National Archives—among them, deeds of sale, wills and other paper documents.

“This ‘boring stuff’ is almost always dated,” says Sethares. “So if we can go through the archives and match those pieces of paper up with Rembrandt’s, that will at least get us to within a couple of years.”

Eventually, Sethares says he would like to build a second WImSy system and create a repository of papers photographed by the device that other researchers could access to date artworks and documents. He’s still figuring out some of the finer details, though, like who owns the images taken with the system and who should have access to them. In the meantime, WImSy is making the rounds of European museums whose researchers are eager to experiment with the system before it returns to museums in the United States.

More information:

Elisa Ou et al, The Watermark Imaging System: Revealing the Internal Structure of Historical Papers, Heritage (2023). DOI: 10.3390/heritage6070270

Provided by

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Citation:

Cracking the da Vinci chronology: System tries to bring order to the works of a Renaissance genius (2023, November 14)