As wildfire risk rises in the West, wildland firefighters and officials are keeping a closer eye on the high mountains – regions once considered too wet to burn.

The growing fire risk in these areas became startling clear in 2020, when Colorado’s East Troublesome Fire burned up and over the Continental Divide to become the state’s second-largest fire on record. The following year, California’s Dixie Fire became the first on record to burn across the Sierra Nevada’s crest and start down the other side.

We study wildfire behavior as climate scientists and engineers. In a new study, we show that fire risk has intensified in every region across the West over the past four decades, but the sharpest upward trends are in the high elevations.

In 2020, Colorado’s East Troublesome fire jumped the Continental Divide.

AP Photo/David Zalubowski

High mountain fires can create a cascade of risks for local ecosystems and for millions of people living farther down the mountains.

Since cooler, wetter high mountain landscapes rarely burn, vegetation and dead wood can build up, so highland fires tend to be intense and uncontrollable. They can affect everything from water quality and the timing of meltwater that communities and farmers rely on, to erosion that can bring debris and mud flows. Ultimately, they can change the hydrology, ecology and geomorphology of the highlands, with complex feedback loops that can transform mountain landscapes and endanger human safety.

Four decades of rising fire risk

Historically, higher moisture levels and cooler temperatures created a flammability barrier in the highlands. This enabled fire managers to leave fires that move away from human settlements and up mountains to run their course without interference. Fire would hit the flammability barrier and burn out.

However, our findings show that’s no longer reliable as the climate warms.

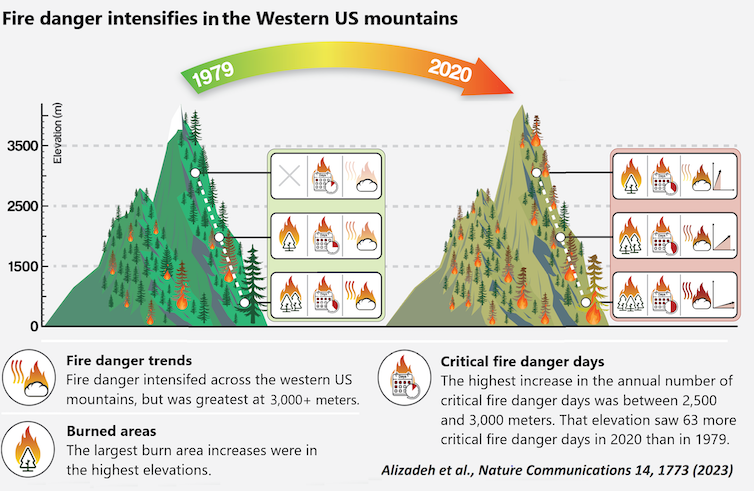

We analyzed fire danger trends in different elevation bands of the Western U.S. mountains from 1979 to 2020. Fire danger describes conditions that reflect the potential for a fire to ignite and spread.

Over that 42-year period, rising temperatures and drying trends increased the number of critical fire danger days in every region in the U.S. West. But in the highlands, certain environmental processes, such as earlier snowmelt that allowed the earth to heat up and become drier, intensified the fire danger faster than anywhere else. It was particularly stark in high-elevation forests from about 8,200 to 9,800 feet (2,500-3,000 meters) in elevation, just above the elevation of Aspen, Colorado.

Mohammad Reza Alizadeh, CC BY

We found that the high-elevation band had gained on average 63 critical fire danger days a year by 2020 compared with 1979. That included 22 days outside the traditional warm season of May to September. In previous research, we found that high-elevation fires had been…