In Rector, Pa., researchers have spotted one strange bird.

This rose-breasted grosbeak has a pink breast spot and a pink “wing pit” and black feathers on its right wing — telltale shades of males. But on its left side, the songbird displays yellow and brown plumage, hues typical of females.

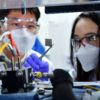

Annie Lindsay had been out capturing and banding birds with identification tags with her colleagues at Powdermill Nature Reserve in Rector on September 24 when a teammate hailed her on her walkie-talkie to alert her of the bird’s discovery. Lindsay, who is banding program manager at Powdermill, immediately knew what she was looking at: a half-male, half-female creature known as a gynandromorph.

“It was spectacular. This bird is in its nonbreeding [plumage], so in the spring when it’s in its breeding plumage, it’s going to be even more starkly male, female,” Lindsay says. The bird’s colors will become even more vibrant, and “the line between the male and female side will be even more obvious.”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Such birds are rare. Lindsay has seen only one other similar, but less striking, bird 15 years ago, she says.

Gynandromorphs are found in many species of birds, insects and crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters. This bird is likely the result of an unusual event when two sperm fertilize an egg that has two nuclei instead of one. The egg can then develop male sex chromosomes on one side and female sex chromosomes on the other, ultimately leading to a bird with a testis and other male characteristics on one half of its body and an ovary and other female qualities on the other half.

Unlike hermaphrodites, which also have genitals of both sexes, gynandromorphs are completely male on one side of the body and female on the other.

Scientists don’t know if these birds behave more like males or females, or if they can reproduce. UCLA biologist Arthur Arnold studied one gynandromorph zebra finch that used a male song and behavior to attract females. But there need to be more studies on whether behavior related to one sex is more dominant than the other across gynandromorphs, he says. Such research is tough, however, because the creatures are so rare.

In 64 years of bird banding, Powdermill’s Avian Research Center has recorded fewer than 10 such birds. After marveling over their new find in the field, Lindsay and her colleagues took the rose-breasted grosbeak (Pheucticus ludovicianus) to the laboratory, measured its wing span and plucked out four feathers to obtain its DNA for future studies. The team later took photographs and TikTok videos with the tiny feathery guest before letting it fly on its way.