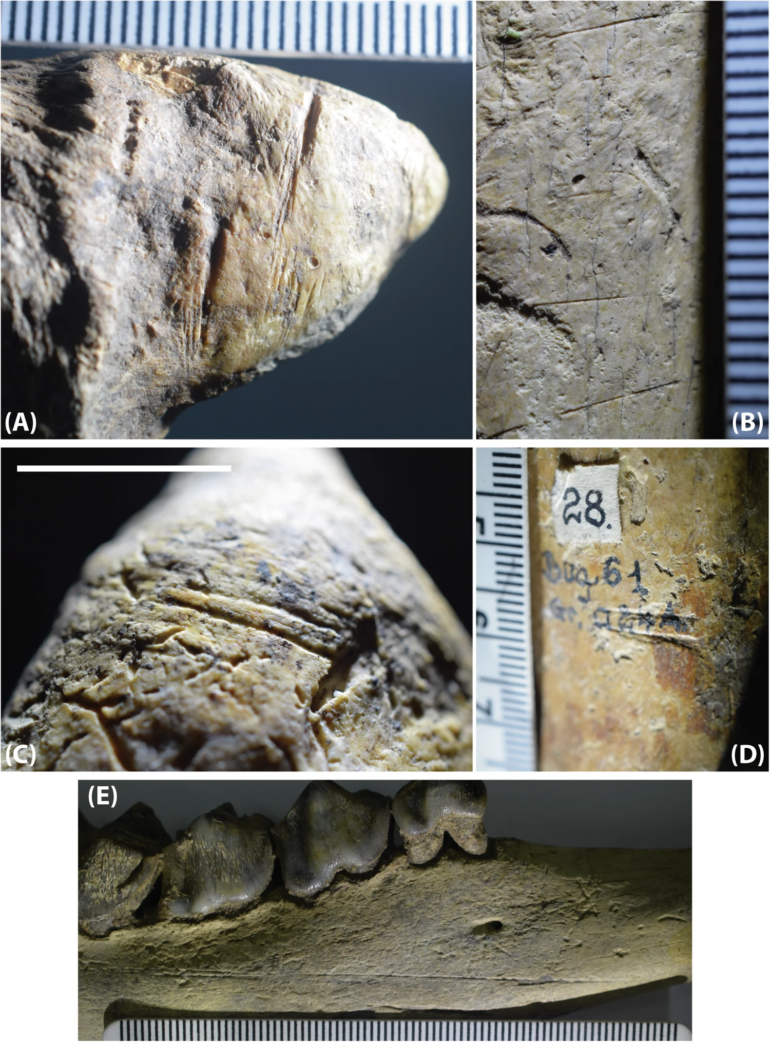

Looking again through the magnifying lens at the fossil’s surface, one of us, Sabrina Curran, took a deep breath. Illuminated by a strong light positioned nearly parallel to the surface of the bone, the V-shaped lines were clearly there on the fossil. There was no mistaking what they meant.

She’d seen them before, on bones that were butchered with stone tools about 1.8 million years ago, from a site called Dmanisi in Georgia. These were cut marks made by a human ancestor wielding a stone tool. After staring at them for what felt like an eternity − but was probably only a few seconds − she turned to our colleagues and said, “Hey … I think I found something.”

What she’d spotted in 2017 was our team’s first evidence that hominins butchered several animals at the site of Grăunceanu, in Romania, at least 1.95 million years ago. Before this discovery, those other cut marks from Dmanisi were the oldest well-dated evidence in Eurasia of the presence of hominins − our direct human ancestors.

Other scientists have reported sites in Eurasia and northern Africa with either hominin fossils, stone tools or butchered animal bones from around this time. Our recently published research adds to this story with well-dated, verified evidence that hominins of some kind had spread to this part of the world by around 2 million years ago.

Romanian site with fossilized animal bones

A 1960s photo of fossil bones before they were excavated from the ground at Grăunceanu, Romania.

Emil Racoviță Institute of Speleology

A little background on Grăunceanu: This open-air site was originally excavated in the 1960s, and researchers found thousands of fossil animal bones there. It’s one of the best-known Early Pleistocene sites in East-Central Europe. Many of the fossil animal bones are quite complete and at the time of excavation lay together as they were positioned in life. The original deposition was called a “bone nest” because of how densely packed the bones were.

If you were to stand on the hillside surrounding Grăunceanu almost 2 million years ago, it would likely have seemed familiar: a river channel surrounded by a forest that fades into more open grasslands to the foothills. Occasionally that river floods its banks, inundating the valley with rich soils, providing nutrients for the plants that the resident animals feed on. All pretty familiar, until you look more closely at those animals: ostriches, pangolins, giraffes, saber-toothed cats and hyenas − in Europe!

It’s the fossil bones of these ancient animal inhabitants that were excavated at Grăunceanu. Unfortunately, most of the excavation records and provenance data for the site have been lost. Even without those, though, the Grăunceanu fossils are so remarkably preserved that they offer up a wealth of paleontological information.

A few years after finding those first cut marks, our team, including biological anthropologist