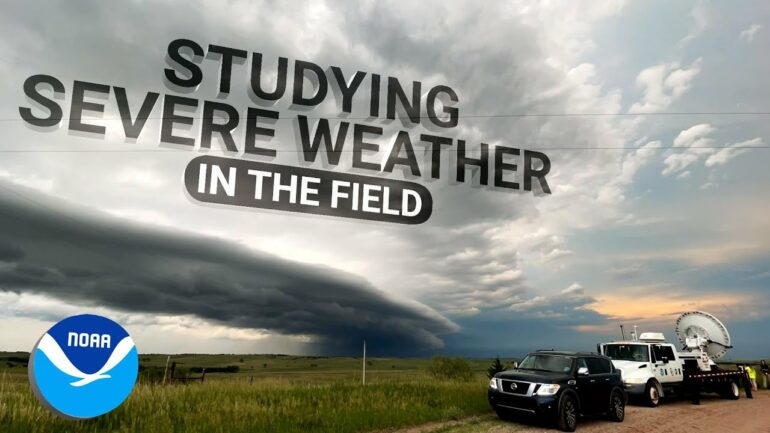

Storm-chasing for science can be exciting and stressful – we know, because we do it. It has also been essential for developing today’s understanding of how tornadoes form and how they behave.

In 1996, the movie “Twister” with Helen Hunt brought storm-chasing scientists into the public imagination and inspired a generation of atmospheric scientists.

With the new “Twisters” movie hitting theaters, we’ve been getting questions about storm-chasing – or storm intercepts, as we call them.

Here are some answers about what scientists who do this kind of fieldwork are really up to when they race off after storms.

Scientists with the National Severe Storms Lab ‘intercepted’ this tornado to collect data using mobile radar and other instruments on May 24, 2024.

National Severe Storms Lab

What does a day of storm-chasing really look like?

The morning of a chase day starts with a good breakfast, because there might not be any chance to eat a good meal later in the day. The team looks at the weather conditions, the National Weather Service computer forecast models and outlooks from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Storm Prediction Center to determine the target.

Our goal is to figure out where tornadoes are most likely to occur that day. Temperature, moisture and winds, and how these change with height above the ground, all provide clues.

There is a “hurry up and wait” cadence to a storm chase day. We want to get into position quickly, but then we’re often waiting for storms to develop.

A ‘hook echo’ on radar, typically a curl at the back of a storm cell, is one sign that a tornado could form. The hook reflects precipitation wrapping around the back side of the updraft.

National Severe Storms Lab

Storms often take time to develop before they’re capable of producing tornadoes. So we watch the storm carefully on radar and with our eyes, if possible, staying well ahead of it until it matures. Often, we’ll watch multiple storms and look for signs that one might be more likely to generate tornadoes.

Once the mission scientist declares a deployment, everyone scrambles to get into position.

We use a lot of different instruments to track and measure tornadoes, and there is an art to determining when to deploy them. Too early, and the tornado might not form where the instruments are. Too late, and we’ve missed it. Each instrument needs to be in a specific location relative to the tornado. Some need to be deployed well ahead of the storm and then stay stationary. Others are car-mounted and are driven back and forth within the storm.