Over the past century, the Earth’s average temperature has swiftly increased by about 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit). The evidence is hard to dispute. It comes from thermometers and other sensors around the world.

But what about the thousands of years before the Industrial Revolution, before thermometers, and before humans warmed the climate by releasing heat-trapping carbon dioxide from fossil fuels?

Back then, was Earth’s temperature warming or cooling?

Even though scientists know more about the most recent 6,000 years than any other multimillennial interval, studies on this long-term global temperature trend have come to contrasting conclusions.

To try to resolve the difference, we conducted a comprehensive, global-scale assessment of the existing evidence, including both natural archives, like tree rings and seafloor sediments, and climate models. Our results, published Feb. 15, 2023, suggest ways to improve climate forecasting to avoid missing some important slow-moving, naturally occurring climate feedbacks.

Global warming in context

Scientists like us who study past climate, or paleoclimate, look for temperature data from far back in time, long before thermometers and satellites.

We have two options: We can find information about past climate stored in natural archives, or we can simulate the past using climate models.

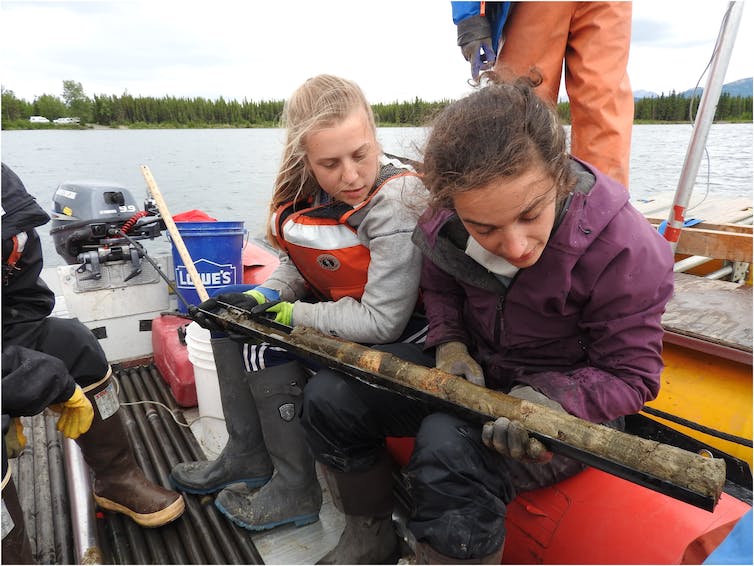

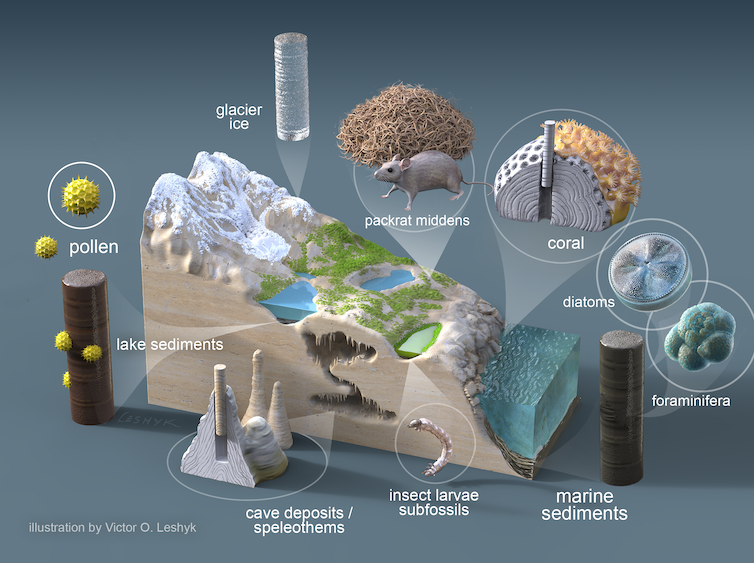

There are several natural archives that record changes in the climate over time. The growth rings that form each year in trees, stalagmites and corals can be used to reconstruct past temperature. Similar data can be found in glacier ice and in tiny shells found in the sediment that builds up over time at the bottom of the ocean or lakes. These serve as substitutes, or proxies, for thermometer-based measurements.

Trees are the best-known natural archives. Here are several others that hold evidence of past temperature. Cores or other samples from these archives can be used to reconstruct changes over time.

Viktor O. Leshyk, Author provided

For example, changes in the width of tree rings can record temperature fluctuations. If temperature during the growing season is too cold, the tree ring forming that year is thinner that one from a year with warmer temperatures.

Another temperature proxy is found in seafloor sediment, in the remains of tiny ocean-dwelling creatures called foraminifera. When a foraminifer is alive, the chemical composition of its shell changes depending on the temperature of the ocean. When it dies, the shell sinks and gets buried by other debris over time, forming layers of sediment at the ocean floor. Paleoclimatologists can then extract sediment cores and chemically analyze the shells in those layers to determine their composition and age, sometimes going back millennia.