A team of US scientists has demonstrated that the offspring of huge carnivorous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex, who grew from the size of house cats to towering monsters, reshaped their ecosystems by outcompeting smaller rival species.

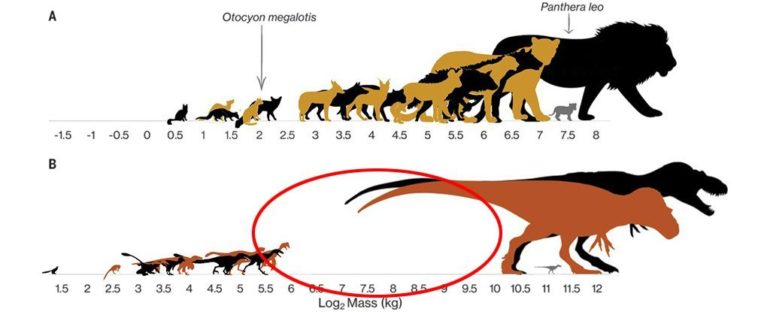

Their study, published in the journal Science on Thursday, helps answer an enduring mystery about the 150-million-year rule of dinosaurs: why were there many more large species compared to small, which is the opposite of what we see in land animals today?

“Dinosaur communities were like shopping malls on a Saturday afternoon, jam-packed with teenagers,” said Kat Schroeder, a graduate student at the University of New Mexico who led the research.

“They made up a significant portion of the individuals in a species and would have had a very real impact on the resources available in communities.”

Even given the limitations of the fossil record, it’s thought that overall, dinosaurs were not particularly diverse: there are only some 1,500 known species, compared to tens of thousands of modern mammalian and bird species.

What’s more, across the entirety of the Mesozoic era, from 252 to 66 million years ago, there were relatively many more species of large bodied dinosaurs weighing 1,000 kilograms (a ton) compared to species weighing less than 60 kilograms (130 pounds).

Some scientists put forward the idea that since even the most gigantic dinosaurs begin life as tiny hatchlings, they could be using different resources as they were growing up – occupying the space in ecosystems where smaller species might otherwise flourish.

To test the theory, Schroeder and her colleagues examined data from fossil sites around the world, including over 550 dinosaur species, and organized the dinosaurs by whether they were herbivores or carnivores, as well as their sizes.

They discovered a striking gap in the presence of medium-sized carnivores in every community that had megatheropods, or giant predators like the T. rex.

“Very few carnivorous dinosaurs between 100-1,000 kilograms (200 pounds to one ton) exist in communities that have megatheropods,” Schroeder said.

“And the juveniles of those megatheropods fit right into that space.”

Treating juveniles as a species

The conclusion was supported by the way dinosaur diversity changed over time. Jurassic communities (200-145 million years ago) had smaller gaps and Cretaceous communities (145-65 million years ago) had large ones.

That’s because Jurassic megatheropods teenagers were more like adults, and there was a wider variety of herbivorous long-necked sauropods (like the brachiosaurus) for them to prey on.

“The Cretaceous, on the other hand, is completely dominated by tyrannosaurs and abelisaurs, which change a lot as they grow,” said Schroeder.

To mathematically test their theory, the team multiplied juvenile megatheropods’ mass at given ages by how many were expected to survive each year, based on fossil records.

This statistical method, which effectively treated juveniles as their own species, neatly squared away the observed gaps of medium-sized carnivores.

Beyond helping resolve a longstanding question, the research shows the value of applying ecological considerations to dinosaurs, said Schroeder.

“I think we’re shifting a little bit more towards understanding dinosaurs as animals as opposed to looking at dinosaurs as just cool rocks, which is where paleontology started and has been for a long time,” she said.

Agence France-Presse