The International Space Station is one of the most remarkable achievements of the modern age. It is the largest, most complex, most expensive and most durable spacecraft ever built.

Its first modules were launched in 1998. The first crew to live on the International Space Station – an American and two Russians – entered it in 2000. Nov. 2, 2025, marks 25 years of continuous habitation by at least two people, and as many as 13 at one time. It is a singular example of international cooperation that has stood the test of time.

Two hundred and ninety people from 26 countries have now visited the space station, several of them staying for a year or more. More than 40% of all the humans who have ever been to space have been International Space Station visitors.

The station has been the locus of thousands of scientific and engineering studies using almost 200 distinct scientific facilities, investigating everything from astronomical phenomena and basic physics to crew health and plant growth. The phenomenon of space tourism was born on the space station. Altogether, astronauts have accumulated almost 127 person-years of experience on the station, and a deep understanding of what it takes to live in low Earth orbit.

A view of the European Space Agency’s Columbus laboratory module on the International Space Station.

Paolo Nespoli and Roland Miller, courtesy of NASA and ASI.

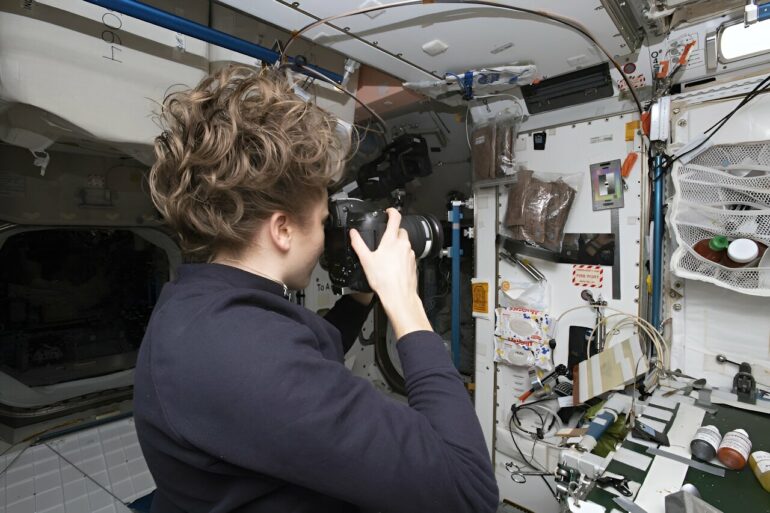

If you’ve ever seen photos of the inside of the International Space Station, you’ve probably noticed the clutter. There are cables everywhere. Equipment sticks out into corridors. It doesn’t look like Star Trek’s Enterprise or other science fiction spacecraft. There’s no shower for the crew, or a kitchen for cooking a meal from scratch. It doesn’t have an area designed for the crew to gather in their downtime. But even without those niceties, it clearly represents a vision of the future from the past, one where humanity would live permanently in space for the first time.

Space archaeology

November 2025, by coincidence, also marks the 10th anniversary of my team’s research on the space station, the International Space Station Archaeological Project. The long history of habitation on the space station makes it perfect for the kind of studies that archaeologists like my colleagues and me carry out.

We recognized that there had been hardly any research on the social and cultural aspects of life in space. We wanted to show space agencies that were already planning three-year missions to Mars what they were overlooking.

We wanted to go beyond just talking to the crew about their experiences, though we have also done that. But as previous studies of contemporary societies have shown, people often don’t want to discuss all their lives with researchers, or they’re unable to articulate all their experiences.

Astronauts on Earth are usually trying to get their next ride back to space, and they understandably…