Human evolution is tightly connected to the environment and landscape of Africa, where our ancestors first emerged.

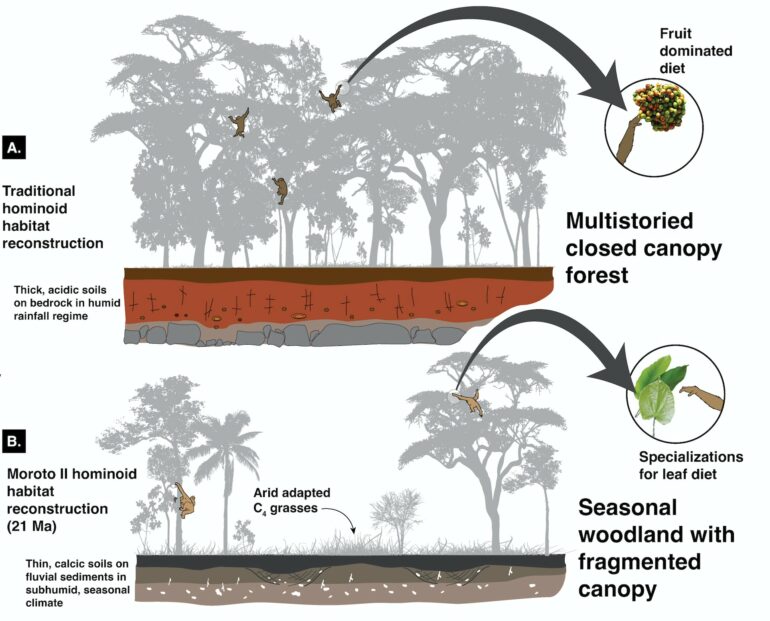

According to the traditional scientific narrative, Africa was once a verdant idyll of vast forests stretching from coast to coast. In these lush habitats, around 21 million years ago, the earliest ancestors of apes and humans first evolved traits – including upright posture – that distinguished them from their monkey cousins.

But then, the story went, global climates cooled and dried, and forests began to shrink. By about 10 million years ago, grasses and shrubs that were better able to tolerate the increasingly dry conditions started to take over eastern Africa, replacing forests. The earliest hominins, our distant ancestors, ventured out of the forest remnants that had been home onto the grass-covered savanna. The idea was that this new ecosystem pushed a radical change for our lineage: We became bipedal.

For a long time, researchers have linked the expansion of grasslands in Africa to the evolution of numerous human traits, including walking on two legs, using tools and hunting.

Despite the prominence of this theory, mounting evidence from paleontological and paleoclimatological research undermines it. In two recent papers, our multidisciplinary team of Kenyan, Ugandan, European and American scientists concluded that it is time finally to discard this version of the evolutionary story.

A decade ago, we began what, at the time, was a unique experiment in paleoanthropology: Several independent research teams joined together to build a regional perspective on the evolution and diversification of early apes. The project, dubbed REACHE, short for Research on Eastern African Catarrhine and Hominoid Evolution, was based on the premise that conclusions drawn from evidence across many locations would be more powerful than interpretations from individual fossil sites. We wondered whether previous researchers had missed the forest for the trees.

An ape in Uganda 21 million years ago

Based on the lifestyle of apes alive today, scientists have hypothesized that the very first ones evolved in dense forests, where they successfully fed on fruit, thanks to a few key anatomical innovations.

Chimpanzees move with an upright posture.

Apes have stable, upright backs. Once the back is vertical, an ape no longer has to walk on the top of small branches like a monkey. Instead, it can grab different branches with its arms and legs, distributing its body mass across multiple supports. Apes can even hang below branches, making them less likely to lose their balance. In this way, they are able to access fruits growing on the edges of tree crowns that otherwise might be available only to smaller species.

But was this scenario true for the earliest apes? A 21 million-year-old site in Moroto, Uganda, became an ideal place to investigate this question. There our REACHE…