Flatfish and shrimp are caught in the North Sea by using trawls that are dragged across the seabed. This releases carbon into the water and carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, as shown by the latest research at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon.

The study is part of the collaborative project APOC. Partners are the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel and the German Federation for the Environment and Nature Conservation (BUND).

The study aims to reduce the uncertainty in the quantitative assessment of the impact of bottom trawling on carbon storage in the North Sea and global shelf seas. The scientists analyzed more than 2,300 sediment samples from the North Sea. The results were recently published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

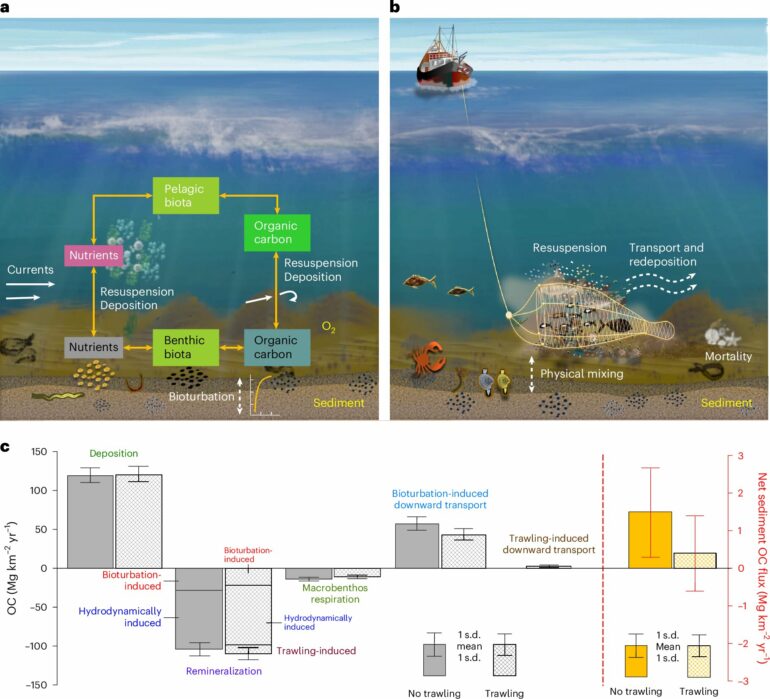

Normally, the seabed acts as a carbon sink. This means that it stores more carbon than it releases. Researchers from the Hereon Institute of Coastal Systems–Analysis and Modeling have now discovered together with the APOC partners that this function is being impaired by the use of bottom trawls in fisheries.

Geophysicist and lead author Dr. Wenyan Zhang states, “We found that sediment samples collected in intensely trawled areas contained lower amounts of organic carbon than samples collected in areas with less fishing. We were able to attribute this effect to bottom trawling with high confidence.

“Moreover, our methods greatly reduce the uncertainty in quantitative assessments of the impact at regional to global scales compared to earlier estimates.”

Computer simulations have also shown that the carbon concentration in the seabed has decreased continuously throughout the past decades as a result of intensive trawling. Soft, muddy bottoms are particularly susceptible.

Millions of tons of CO2 released

The sediments in the seabed bind carbon. Animals living at the seafloor consume this carbon, but also shift it into deeper layers of soil by burrowing and digging, where it can be stored for millennia. The trawls used by fisheries have the opposite effect: they stir up the sediments.

They also damage habitats, causing plants and animals to die off. This causes carbon from the low-oxygen environment in the sediment to enter the water column, where oxygen is more abundant. There, it is converted to CO2 by microorganisms such as bacteria. Part of the CO2 can be released into the atmosphere, where it acts as a greenhouse gas and intensifies climate change.

According to the calculations by the authors, trawling in the North Sea releases about 1 million tons of CO2 from sediments every year. Worldwide, the figure is estimated to be about 30 million tons. This estimate is less than 10% of earlier global estimates in which the critical feedback loops between trawling, particle dynamics and benthic fauna were missing. These dynamic feedback loops are now considered in the numerical model developed at Hereon.

Better protection of muddy seabeds

“Our results point to the need for special protection of muddy habitats in marginal seas such as the North Sea,” says Zhang. So far, marine protection measures have mainly been implemented in areas with hard, sandy bottoms and reefs.

Although these areas are ecologically diverse, they store less carbon. “Our methods and results might be used in optimizing marine spatial planning policies to gauge the potential carbon benefits of limiting or ending bottom trawling within protected areas,” says Zhang.

More information:

Wenyan Zhang et al, Long-term carbon storage in shelf sea sediments reduced by intensive bottom trawling, Nature Geoscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-024-01581-4

Provided by

Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres

Citation:

Intensive fishing on the seabed increases the release of carbon, researchers find (2024, October 29)