On Sept. 20, 2024, a newspaper in Montana reported an issue with ballots provided to overseas voters registered in the state: Kamala Harris was not on the ballot. Election officials were able to quickly remedy the problem but not before accusations began to spread online, primarily among Democrats, that the Republican secretary of state had purposefully left Harris off the ballot.

This false rumor emerged from a common pattern: Some people view evidence such as good-faith errors in election administration through a mindset of elections being untrustworthy or “rigged,” leading them to misinterpret that evidence.

As the U.S. approaches another high-stakes and contentious election, concerns about the pervasive spread of falsehoods about election integrity are again front of mind. Some election experts worry that false claims may be mobilized – as they were in 2020 – into efforts to contest the election through tactics such as lawsuits, protests, disruptions to vote-counting and pressure on election officials to not certify the election.

Our team at the University of Washington has studied online rumors and misinformation for more than a decade. Since 2020, we have focused on rapid analysis of falsehoods about U.S. election administration, from sincere confusion about when and where to vote to intentional efforts to sow distrust in the process. Our motivations are to help quickly identify emerging rumors about election administration and analyze the dynamics of how these rumors take shape and spread online.

Through the course of this research we have learned that despite all the discussion about misinformation being a problem of bad facts, most misleading election rumors stem not from false or manipulated evidence but from misinterpretations and mischaracterizations. In other words, the problem is not just about bad facts but also faulty frames, or the mental structures people rely on to interpret those facts.

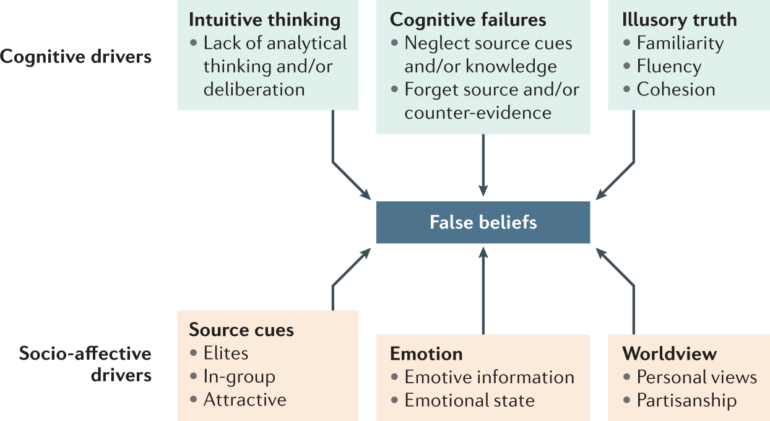

Misinformation may not be the best label for addressing the problem – it’s more an issue of how people make sense of the world, how that sensemaking process is shaped by social, political and informational dynamics, and how it begets rumors that can lead people to a false understanding of events.

Rumors – not misinformation

There is a long history of research on rumors going back to World War II and earlier. From this perspective, rumors are unverified stories, spreading through informal channels that serve informational, psychological and social purposes. We are applying this knowledge to the study of online falsehoods.

Though many rumors are false, some turn out to be true or partially true. Even when false, rumors can contain useful indications of real confusions or fears within a community.

Rumors can be seen as a natural byproduct of collective sensemaking – that is, efforts by groups of well-meaning people to make sense of uncertain and ambiguous information during dynamic events. But rumors can…