A collaborative team of physicists and microbiologists from UNIST and Stanford University has, for the first time, uncovered the fundamental laws governing the distribution of self-propelled particles, such as bacteria.

Published in Physical Review Letters, this breakthrough has been jointly led by Professor Joonwoo Jeong in the UNIST Department of Physics, Professor Robert J. Mitchell in the UNIST Department of Biological Sciences, and Professor Sho C. Takatori at Stanford University.

The study reveals that the distribution of living bacteria is governed by a delicate balance between their motility and their affinity for specific liquid environments. Interestingly, the findings highlight a phenomenon consistent with the like-attracts-like principle.

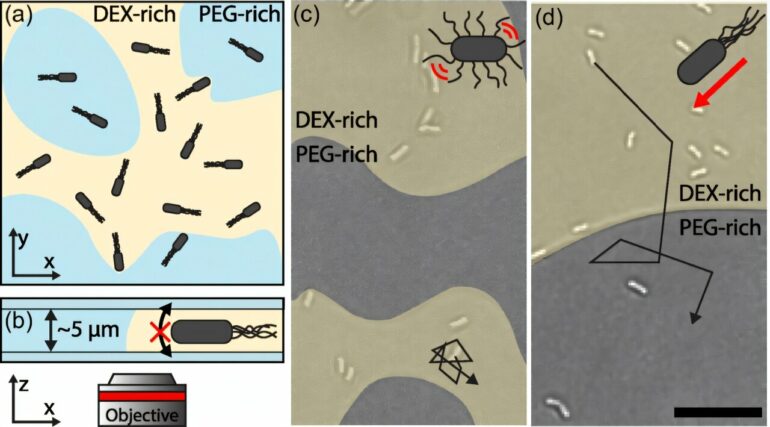

Motile bacteria tend to aggregate with other bacteria exhibiting similar motility behaviors, influencing their spatial distribution within complex fluids. While forces that draw bacteria into certain liquids tend to confine them, the bacteria’s ability to move allows them to escape these confinements and distribute more broadly—challenging traditional expectations based solely on energy preferences.

Using optical tweezers, the researchers precisely measured the forces bacteria exert to favor one liquid phase over another, finding that this attractive force is approximately 1 piconewton (pN)—a force about 10 million times weaker than what is experienced by a human hair under gravity.

Remarkably, the bacteria’s propulsion force was measured at around 10 pN, sufficient to overcome these weak attractive forces and enable bacteria to traverse between phases, further illustrating how motility influences distribution in active matter systems.

The experiments involved injecting Bacillus subtilis—a bacterium commonly used in fermented soybean products—into a two-phase dextran/PEG system, which naturally separates into dextran-rich and PEG-rich phases.

While non-motile bacteria remained confined to their preferred phase, motile bacteria were evenly distributed across both, a phenomenon that cannot be explained solely by thermal fluctuations.

Instead, the motile bacteria exhibit a form of like-attracts-like behavior, where their self-propulsion and mutual attraction lead them to cluster with similar bacteria, influencing their phase partitioning.

Key contributors include Dr. Jiyong Cheon, a former doctoral student at UNIST, now working as a postdoctoral researcher at Georgia Tech, and Kyu Hwan Choi, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University.

The team emphasized that this interdisciplinary work—spanning physics, chemical engineering, and microbiology—has successfully quantified the forces acting on active particles in non-equilibrium conditions.

This model system offers new insights into how bacteria and other active particles behave in environments where energy is continuously supplied or consumed, reinforcing the idea that like behaviors tend to attract and influence collective dynamics.

Professor Jeong explained, “This research not only helps us understand how bacteria establish their niches within the body, but also has potential applications in protein purification, biosensor development, and the design of micro-robots.”

More information:

Jiyong Cheon et al, Motility Modulates the Partitioning of Bacteria in Aqueous Two-Phase Systems, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/6gm5-cnv1. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2405.08995

Provided by

Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology

Citation:

Bacterial motility helps uncover how self-propelled particles distribute in active matter systems (2025, October 24)