The emergence of vaccines against Covid-19 has been hailed as gamechanger by experts, but polls have revealed the speed of their development and approval is a matter of concern for some people. We take a look at how and why such processes were so rapid.

How long does it normally take to develop a vaccine from scratch?

Traditionally it is a slow process. Speaking at the joint Commons and Lords national security strategy committee in October, Sir Patrick Vallance said that before Covid, it took an average of about 10 years to develop a completely new vaccine, with the process never before achieved in less than about five years.

How has it been possible to develop vaccines against Covid-19 in less than a year?

A key consideration is funding – public and private cash has been poured into the race for a Covid vaccine, pushing aside the usual financial concerns facing pharmaceutical companies. What’s more, demand and urgency are high.

“The fact that governments pre-bought the vaccines meant that people could take greater risks with what they did at an earlier stage without having to take one step at a time,” said Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Traditionally, vaccines are developed by weakening it or killing a virus, or by producing part of the virus in the lab. However this is time consuming.

Instead, both the Oxford University/AstraZeneca and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines were developed using different “platform technologies” that involve slotting genetic material from the virus into a tried and tested delivery package. Once introduced into the human body this genetic material is used by the protein-making machinery in our cells to churn out the coronavirus “spike protein”, triggering an immune response.

This approach was aided by the speed at which scientists in China identified and shared the genetic sequence of the new coronavirus, and work that was already under way on other coronaviruses.

But while such platform technologies are a non-traditional approach, that does not mean they are untested.

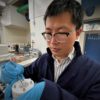

“The mRNA vaccine platform technology [which the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine uses] has been in development for over two decades,” said Dr Zoltán Kis, of Imperial College London.

The use of platform technologies not only means a vaccine can be rapidly developed, and that more is known about its safety profile from the start, but production is faster and cheaper as existing production processes can be used.

Another consideration is that while in traditional vaccine development the phases of clinical trials are carried out in sequence, in the case of the Covid vaccines they have overlapped, making the process faster.

“Vaccine manufacturing has also been carried out in parallel with the clinical trials, hoping that trials will succeed,” said Kis.

Evans added that the large trial sizes and duration was reassuring. “I have seen no corners that have been cut,” he said.

Finally, advances in tech have streamlined data-recording, while the advent of social media has made it easier to recruit trial participants – something aided by a strong public desire to help.

“It normally takes weeks or months to recruit to a study. This one, it kind of happened overnight,” said Prof Adam Finn, a vaccine expert at the University of Bristol and an investigator on the Oxford/AstraZeneca trials.

What about approval?

Dr Penny Ward, visiting professor in pharmaceutical medicine at King’s College London and chair of the education and standards committee of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Medicine said it typically took about six to nine months for new medicines to be approved. But that is in part because the necessary data is often delivered to regulatory agencies in one go.

In the case of the Covid-19 vaccines, the process has been accelerated by what is known as a “rolling review”, with information released to the regulators as it was acquired.

“Rolling review is a very new thing to be done,” said Evans, noting that companies normally wait to make an application until all data is in because the approval process is expensive and risky for them.

But Ward added the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine had only been given a type of emergency approval by the MHRA, meaning approval will be on a batch-by-batch basis until enough information has been received by the MHRA to assure them there is minimal variability between batches of the vaccine.

How has the UK managed to approve vaccines before Europe and the US?

While there has been much talk about how Brexit might have aided the speedy approval of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine by the MHRA, experts have stressed EU laws allow member states to approve medicines for emergency use without authorisation by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

However Evans said the Brexit transition period might mean the MHRA currently had some extra capacity.

“We are in this slightly weird position where we haven’t had to do the work that we will have to do from 1 January, and we haven’t got the work we’d normally be doing for the EMA,” he said .

But Ward said other factors were important. “In order for [a] product to be approved [by the EMA], the [EU] member states have to agree the conditions of its use,” she said, noting that it took more discussion than if only one state was involved. Another possibility is that Europe may wish to wait to until it is known that there is little variation from batch to batch of vaccine.

Similar considerations could be at play in the US. “The US [Food and Drug Administration] traditionally will not accept or license a product, even in an emergency situation, unless the manufacturing process is fully validated,” said Ward, adding logistical considerations around distribution might also play a role.

“The other thing is that the US decided some time ago that they were [not going to] approve a vaccine without a meeting of the advisory committee on vaccines and biologic products,” she said. “That meeting has been schedule for the 10 December for the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine and the Moderna vaccine is being looked at [on] the 17 December.”