Astronomers have taken detailed observations of an incredibly extreme exoplanet, detecting brutal surface temperatures in the region of 3,200 degrees Celsius (5,792 degrees Fahrenheit).

Those temperatures – measured by the European Space Agency’s CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (or CHEOPS) – are enough to melt all rocks and metals, and even turn them into a gaseous form.

While the exoplanet, named WASP-189b, is not quite as hot as the surface of our Sun (6,000 degrees Celsius or 10,832 degrees Fahrenheit), it’s basically as toasty as some small dwarf stars.

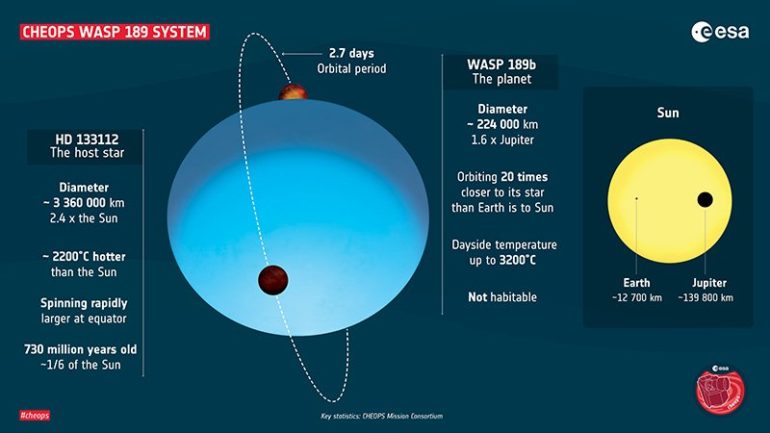

The new findings immediately identify WASP-189b as one of the most extreme planets ever discovered. It has an orbit of just 2.7 days around its star, with one side seeing a permanent ‘day’ and the other side seeing a permanent ‘night’. It’s gigantic, too – about 1.6 times the size of Jupiter.

(ESA)

“WASP-189b is especially interesting because it is a gas giant that orbits very close to its host star,” says astrophysicist Monika Lendl from the University of Geneva in Switzerland. “It takes less than three days for it to circle its star, and it is 20 times closer to it than Earth is to the Sun.”

HD 133112 is the host star in question, 2,000 degrees Celsius (3,600 degrees Fahrenheit) hotter than our Sun, and one of the hottest stars known to have a planetary system around it. CHEOPS made an interesting discovery about this celestial body too: it’s spinning so fast that it’s being pulled outwards at its equator.

WASP-189b is too far away (326 light-years) and too close to HD 133112 to observe directly, but CHEOPS knows some tricks. First, it observed the exoplanet as it passed behind its star: an occultation. Then, it watched as WASP-189b passed in front of its star: a transit.

From these readings, researchers were able to figure out the brightness, temperature, size, shape, and orbital characteristics of the exoplanet, as well as some extra information about the star that it’s circling around.

As it’s on the scale of Jupiter but much closer to its host star, and much hotter, WASP-189b qualifies as a so-called hot Jupiter planet (you can see where the name came from). Scientists are hoping that the information CHEOPS has gathered about WASP-189b will improve our understanding of hot Jupiters in general.

“Only a handful of planets are known to exist around stars this hot, and this system is by far the brightest,” says Lendl. “WASP-189b is also the brightest hot Jupiter that we can observe as it passes in front of or behind its star, making the whole system really intriguing.”

One of the questions that the new CHEOPS research has raised is how WASP-189b was formed in the first place – its inclined orbit suggests it formed further out from HD 133112 and was then driven inwards.

Besides the treasure trove of data this new study has provided, it also shows CHEOPS working as intended and working well, measuring brightness across deep space with a mind-boggling level of accuracy.

The satellite has plenty more missions to move on to next, with hundreds of exoplanets in the queue for closer observation. The data that it collects should teach us more about our own Solar System, as well as the planets outside of it.

“The accuracy achieved with CHEOPS is fantastic,” says planetary scientist Heike Rauer from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Germany. “The initial measurements already show that the instrument works better than expected. It is allowing us to learn more about these distant planets.”

The research has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.