A study on canine brain networks reveals that during mammalian brain evolution, the role of the cingulate cortex, a bilateral structure located deep in the cerebral cortex, was partly taken over by the lateral frontal lobes, which control problem-solving, task-switching, and goal-directed behavior. The study relies on a new canine resting state fMRI brain atlas, which can aid in the analysis of diseases characterized by dysfunctional integration and communication among brain areas.

Researchers interested in how dogs think can not only deduce it from their behavior, but they can also investigate their brain activity using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) to identify and see which areas of the brain are active when the dog reacts to external stimuli. The method identifies the brain mechanisms that influence the dog’s learning and memory, resulting in superior dog training methods as well as knowledge on the evolutionary steps that led to the development of human brain function.

The Department of Ethology at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) has been at the forefront of developing the methodology for canine fMRI measurements since 2006. The training methodology for pet dogs was developed by Márta Gácsi, who has also made significant contributions to the introduction of assistance dog training in Hungary. She adopted many methods from there, complementing them with socially motivated training based on rival training principles discovered through ethological research.

“In this approach, the learner is strongly motivated to learn the task by observing the work of an already trained dog and desiring the praise received for it. As a result of fMRI training, the trained dog is capable of (and eager to!) lie motionless in the MRI scanner for eight minutes, in exchange for expected petting and treats.”

In recent years, canine fMRI has generally involved playing sounds to the animals and investigating which brain areas are activated during the brain processing of the sounds.

Brain activity signals are typically projected onto an anatomical atlas to establish which brain region is affected.

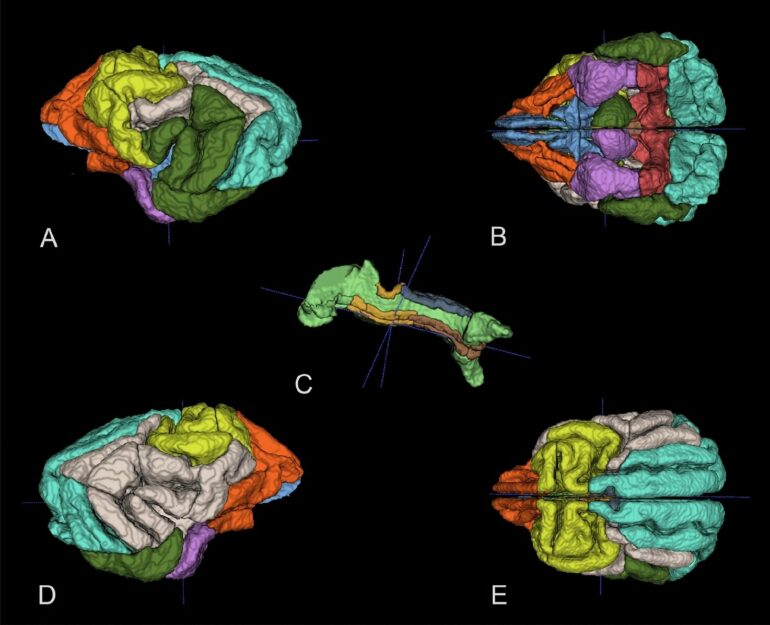

However, the problem is that functional activities are irregular, not necessarily following anatomically defined regular boundaries. Parts of the brain are generally involved in processing specific inputs together, i.e., they act in synchrony, forming a functional brain network. “We have decided to create a dog brain atlas that organizes anatomical regions into functional networks, illustrating which regions belong to a task type and showcasing their locations,” said Dora Szabo, first author of the study published in Brain Structure and Function.

New atlas for dog brain researchers

To create the functional brain atlas, 33 trained family dogs were included in the study. During the fMRI recording, the dogs were not given any task other than to lie still in the scanner. This is the so-called resting state fMRI, or rs-fMRI for short, which examines brain activity without the subject engaging in any specific task, without concentrating or thinking about anything in particular, in a “resting state.” Data obtained this way can reveal which brain areas are functionally related to each other and which are most closely connected, enabling researchers to study brain networks and connections.

The original methodology was further enhanced by applying network theory with the help of Milan Janosov, a network and data scientist at Central European University. While previous research could only describe model-based networks regardless of anatomical boundaries, new canine MRI brain atlases reflecting the anatomical regions at the required resolution enabled researchers to study the strength of connections between network members or between networks, as well as compare species due to the large number of dogs measured.

Brains dominated by different areas in dogs and humans

According to the study, networks in the lateral frontal lobe (frontoparietal) that control problem-solving, task-switching, and goal-directed behavior have a smaller role in dogs than in humans. In their place, the cingulate cortex, a bilateral structure located deep in the cerebral cortex, plays a central role. It is involved in a number of vital processes as well as reward processing and emotion regulation. The cingulate cortex in dogs is proportionally larger than in humans.

The effects of aging

The researchers measured dogs of various ages, the oldest being 14 years old. As mentioned earlier, the dogs must lie motionless to obtain valid measurements.

“The data revealed that older dogs were slightly less capable of maintaining their initial position. This difference, however, was very small, as even in their case, the displacement of the head was less than 0.4 mm. In this aspect, they are similar to humans, as older people also find it more challenging to maintain stillness for extended periods of time compared to younger individuals,” said Eniko Kubinyi, a senior researcher studying cognitive aging in dogs.

The study provides a glimpse into the evolution of the human brain, suggesting that during mammalian brain evolution, the role of the cingulate cortex was partly taken over by frontoparietal regions. In addition, the new rs-fMRI brain atlas can aid in the investigation of conditions in which integration and communication across brain areas are impaired, resulting in a dysfunctional division of tasks. Aging, anxiety, and psychiatric disorders are some examples of such conditions.

More information:

Dóra Szabó et al, Central nodes of canine functional brain networks are concentrated in the cingulate gyrus, Brain Structure and Function (2023). DOI: 10.1007/s00429-023-02625-y

Provided by

Eötvös Loránd University

Citation:

Examining networks in the dog brain provides further insights into mammalian evolution (2023, May 26)