For Arizona State University’s Ph.D. recent graduate Julie Bethany Rakes, it all started as a failed experiment that ended up being an impactful discovery for the microbiology community. Recently in Nature Communications, Rakes and Regents’ Professor Ferran Garcia-Pichel reported on a new bacterium that preys on soil cyanobacteria in biocrusts. In this publication, they describe the newly discovered predator’s life cycle, attack mechanism and its ecological impact.

Bacteria are everywhere and play a major role in maintaining ecological processes all around the world. For instance, in the desert soil, cyanobacteria use photosynthesis to produce energy. Similar to plants, their role in oxygen production and nitrogen fixation is key for the survival of other organisms. Cyanobacteria form communities that live on the soil’s surface forming biocrusts. These communities bring vast benefits by trapping dust, preventing erosion, and increasing nutrients and water level in the soil.

Unfortunately, and despite their role in maintaining the ecosystems, cyanobacteria are the favorite prey of a newly discovered predator: Candidatus Cyanoraptor togatus (C. togatus).

“There was something killing the biocrusts. It was not a virus, and it was not a small animal. It could only be another bacterium,” Garcia-Pichel said.

Healthy cyanobacterial biocrusts resemble soil when they are dry, but when wet, their green pigmentation is visible; except that biocrusts that have been attacked by Cyanoraptor show clearings of cyanobacteria in circular patterns, known as plaques, similar to tiny fairy rings. In the field, researchers were able to identify the disease by observing those unusual plaques.

“I first spotted them in Casa Grande, AZ and then continued this process of watching for rainstorms and immediately running to the field, sometimes driving 6 hours or more to identify them in multiple places in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts,” Rakes said.

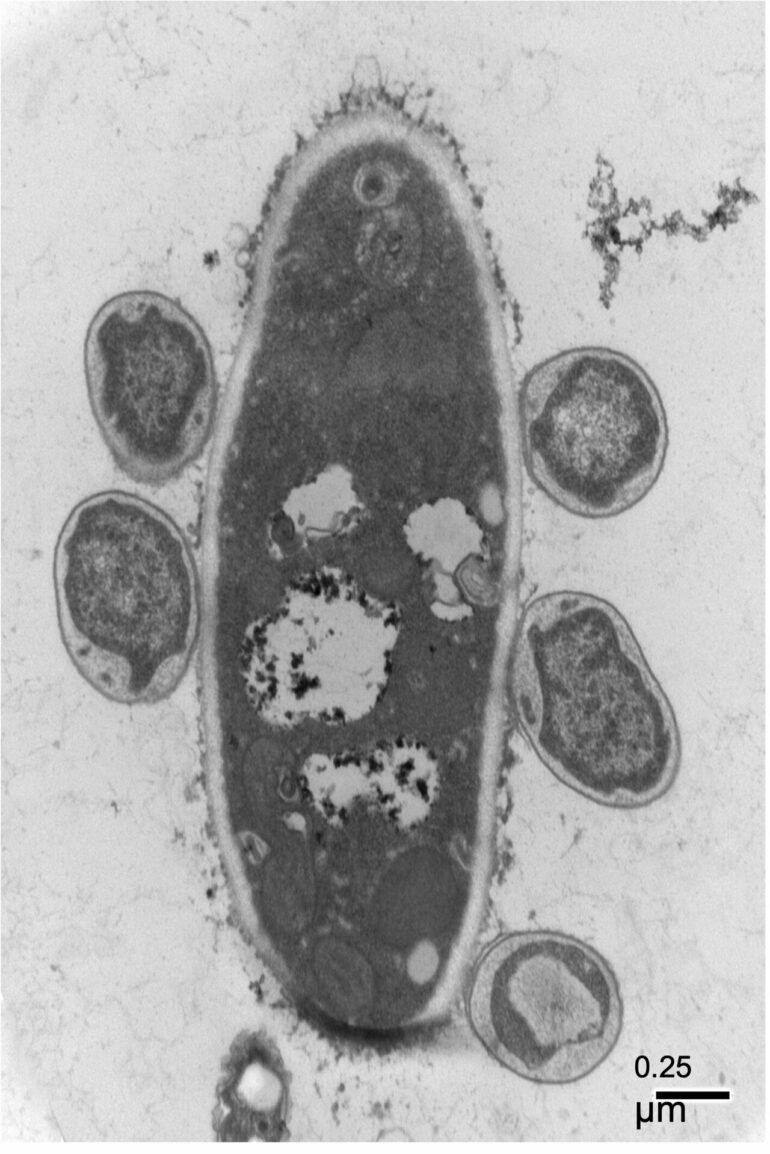

Once inside its prey, Cyanoraptor lodges within the bacterium’s cytoplasm and begins to replicate—growing and dividing until eventually killing the prey and releasing a new army of attack cells. © Julie Bethany Rakes

They worked in the field and in the lab to isolate the disease-causing bacteria. After isolation, bacteria were cultivated and their life cycle and mechanism of attack were established.

In an early stage, Cyanoraptor propagate as tiny spherical cells called propagules. These cells don’t grow or divide; instead they just lurk and patiently wait for their prey. When the cyanobacterium gets close enough, Cyanoraptor attack, attaching to the prey and forming a specialized docking structure, dissolving the prey’s skin-like cell wall, and entering the prey’s cell.

The propagules of Cyanoraptor are weird as far as bacteria go. They have an outer compartment bound by two membranes. Researchers suspect that this compartment plays a key role in the attack, by holding and then releasing proteins that break down their prey’s outer membrane and allow it to enter the weakened cell body. This compartment is also how Cyanoraptor gets its species name, togatus, because they appear to be swathed in a robe, or toga.

Once inside, Cyanoraptor eats away at the prey, growing larger and larger into a sausage-like cell. When it is long enough, this predator starts dividing into many cells all at once, eventually killing the prey and becoming propagules again, waiting for the next unfortunate victim.

“It is a predator that gets into the cells of their prey and eats them from inside, which is horrendous,” Garcia-Pichel said. “It is really like a microbial horror movie.”

As cyanobacteria die, all the things that biocrusts do to benefit the desert are gone. Valuable properties like nitrogen cycling, dust trapping and moisture retention are drastically diminished.

ASU PhD graduate Julie Bethany Rakes first noticed something amiss in the form of circular patterns known as plaques, indicating areas where the cyanobacteria had disappeared. She continued investigating, often waiting until it rained to rush out to the field and look for the telltale signs. © Julie Bethany Rakes

“In general, this means that there could be serious consequences for desert health, fewer nutrients, less stable soil and water retention so a reduction in time plants and other organisms can be active. With the loss of these functions, organisms that rely on these services, such as plants may suffer, which could then have further consequences up the food chain,” Rakes said.

This momentous discovery would not have been possible if it hadn’t been for Rakes’s tenacity, and her refusal to give in to what at first seemed to be a failure. Fortunately for the future of cyanobacteria, she persevered.

Her discovery also demonstrated that predatory bacteria can shape the structure and function of microbial communities around the world, that they are not just and interesting biological rarity.

This experience has given her some wisdom to pass on to other graduate students:

“Follow up on those results that are unexpected or even appear to be flat out wrong,” she said. “When I found myself saying ‘that’s weird,’ it was often something that I just didn’t understand yet. As Ferran wisely told me, ‘In experiments you cannot explain, the microbes are talking to you.'”

The full genome of the newly discovered bacteria can be accessed through the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA730811. Rakes and Ferran are affiliated with the School of Life Sciences and with the Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics. This investigation was done in collaboration with Shannon Lynn Johnson, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, and also a SOLS doctoral alumna.

More information:

Julie Bethany et al, High impact of bacterial predation on cyanobacteria in soil biocrusts, Nature Communications (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-32427-5

Provided by

Arizona State University

Citation:

Researchers discover new predator damaging our ecosystems (2022, September 27)