Cochlear implants are among the most successful neural prostheses on the market. These artificial ears have allowed nearly 1 million people globally with severe to profound hearing loss to either regain access to the sounds around them or experience the sense of hearing for the first time.

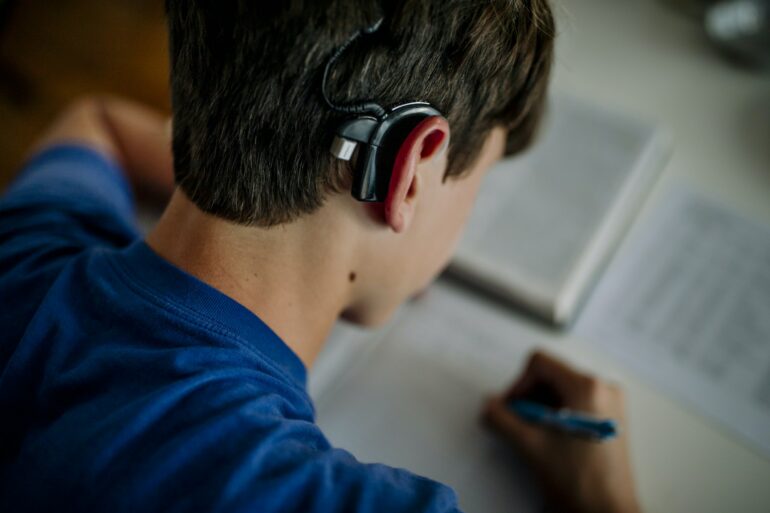

However, the effectiveness of cochlear implants varies greatly across users because of a range of factors, such as hearing loss duration and age at implantation. Children who receive implants at a younger age may may be able to acquire auditory skills similar to their peers with natural hearing.

I am a researcher studying pitch perception with cochlear implants. Understanding the mechanics of this technology and its limitations can help lead to potential new developments and improvements in the future.

How does a cochlear implant work?

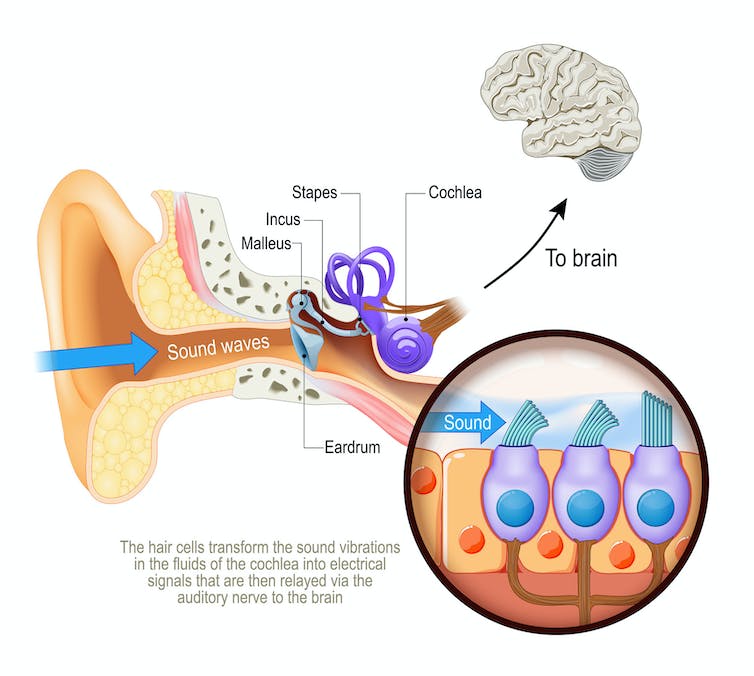

In fully-functional hearing, sound waves enter the ear canal and are converted into neural impulses as they move through hairlike sensory cells in the cochlea, or inner ear. These neural signals then travel through the auditory nerve behind the cochlea to the central auditory areas of the brain, resulting in a perception of sound.

People with severe to profound hearing loss often have damaged or missing sensory cells and are unable to convert sound waves into electrical signals. Cochlear implants bypass these hairlike cells by directly stimulating the auditory nerve with electrical pulses.

Sound travels through the ear canal and is converted by hair cells in the cochlea into electrical signals that enter the brain.

ttsz/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Cochlear implants consist of an external part wrapped behind the ear and an internal part implanted under the skin.

The external unit, which includes a microphone, signal processor and transmitter, picks up and processes sound waves from the environment. It divides sounds into different frequency bands, which are like different channels on a radio, with each band representing a specific range of frequencies within an overall spectrum of sound. It also extracts information about amplitude, or loudness, from each frequency band.

It then transmits that information to the receiver in the internal unit implanted in the cochlea. The electrodes of the internal unit directly stimulate the auditory nerve with electrical pulses based on amplitude information. Electrodes at the base of the cochlea transmit electrical signals containing high-frequency auditory information while electrodes at the top transmit electrical signals containing low-frequency information to the brain, mimicking the frequency analysis in a fully-functioning ear.

Where cochlear implants fall short

While people with cochlear implants are able to detect sounds and perceive speech in quiet environments reasonably well, they often have great difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments, enjoying music and localizing sounds, that is, figuring out which direction…