Solar energy researchers at Oregon State University are shining their scientific spotlight on materials with a crystal structure discovered nearly two centuries ago.

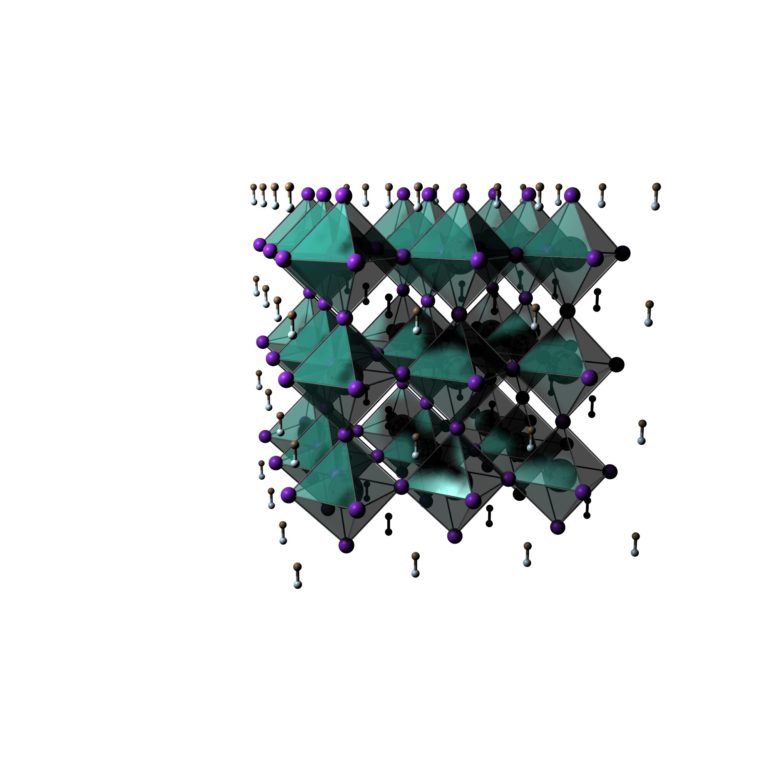

Not all materials with the structure, known as perovskites, are semiconductors. But perovskites based on a metal and a halogen are, and they hold tremendous potential as photovoltaic cells that could be much less expensive to make than the silicon-based cells that have owned the market since its inception in the 1950s.

Enough potential, researchers say, to perhaps someday carve significantly into fossil fuels’ share of the energy sector.

John Labram of the OSU College of Engineering is the corresponding author on two recent papers on perovskite stability, in Communications Physics and the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, and also contributed to a paper published today in Science.

The study in Science, led by researchers at the University of Oxford, revealed that a molecular additive—a salt based on the organic compound piperidine—greatly improves the longevity of perovskite solar cells.

The findings outlined in all three papers deepen the understanding of a promising semiconductor that stems from a long-ago discovery by a Russian mineralogist. In the Ural Mountains in 1839, Gustav Rose came upon an oxide of calcium and titanium with an intriguing crystal structure and named it in honor of Russian nobleman Lev Perovski.

Perovskite now refers to a range of materials that share the crystal lattice of the original. Interest in them began to accelerate in 2009 after a…