The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIRO) has announced it will be making Australia’s share of the Earth observation satellite NovaSAR-1 available to local researchers, in a bid to support local R&D projects and grow the country’s space industry.

CSIRO executive director of digital, national facilities and collections David Williams explained the plan is to operate its share of the satellite as a national facility by giving Australian researchers in industries such as agriculture and natural disaster management the chance to direct the satellite to capture images that support their research.

“Although Australia is one of the largest users of Earth observation data, until now we have not had direct control over the tasking of an Earth observation satellite, so the opening of our NovaSAR-1 facility represents a step change for Australian research and an important step forward for our space industry,” he said.

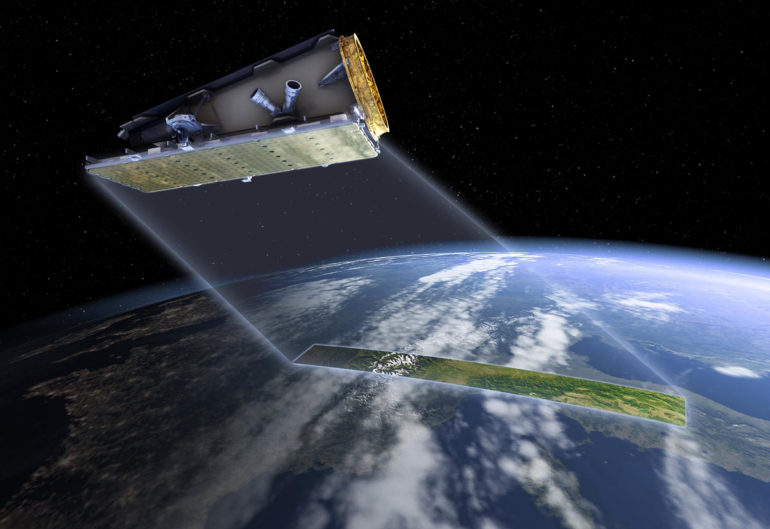

Due to using synthetic aperture radar, NovaSAR-1 can take images of Earth through all weather conditions including clouds, smoke, and also at night.

Having access to such images, according to CSIRO, enables Australian researchers the potential to map, monitor, and manage Australian environments and inform disaster management practices during events such as bushfires and floods.

CSIRO satellite operations and data manager Dr Amy Parker said synthetic aperture radar imagery like the one produced from NovaSAR-1 has not been widely used in Australia before.

“So far, we’ve used the satellite to capture over 1,000 images, all of which are now available to users. NovaSAR-1 is an exciting addition to the country’s Earth observation resources while also helping us to build our capabilities in satellite operations,” she said.

Satellite data captured by NovaSAR-1 is downloaded to a receiving station based in Alice Springs, which is owned by Indigenous-operated ground service provider Centre for Appropriate Technology.

CSIRO said applications to use the NovaSAR-1 national facility will be reviewed by an independent committee and time allocation will awarded based on the scientific merit of each proposed research.

CSIRO secured a 10% share of the NovaSAR-1 satellite for a seven-year period back in September 2017. Under the agreement, CSIRO can direct the satellite to collect any type of data imagery required over Australia and South-East Asia region over an initial 4.5 years, while also be given access to data collected elsewhere around the world. CSIRO is also licensed to use and share the data for research purposes.

Earlier this year, when fronting the Standing Committee of Industry, Innovation, Science and Resources as part of its inquiry into developing Australia’s space industry, Williams warned if Australia were to continue to rely on other countries to provide satellite services, accessing them would present its own set of challenges.

“With the high-resolution [satellites], they’re not switched on all the time, they are reduced and work 10% of the time. They go around the earth in 90 minutes, and they can operate for about nine minutes of that time. The rest of the time its storing energy on solar panels,” he said.

“So, you’re competing for the nine minutes. And when we bought into NovaSAR-1 satellite, we bought two minutes of that nine minutes, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but it is an enormous amount when you look at Australia … we bought it specifically so we could do controlled experimentation and guarantee the data.”

His advice was for Australia to own its own satellite, so the country could access timely data more easily.

“The way to look at it is if you have applications that demand specific timely data or ephemeral data as you’re developing the outcome and you don’t own the satellite, it can be very difficult to get the satellite to switch on and off at the time you want to over the location you need it because there’s competition slots,” he said.

“For example, geological mapping doesn’t change that often, so you have less need for timely information. But for flooding, drought disasters, timely information is everything.

“Bushfire monitoring, for example, if you don’t have real-time access to data, you can’t do it from satellites. To have real-time access to data, you’ve got to have a very good relationship with another country, or you’ve got to own a satellite. That’s a decision for government, rather than a decision for CSIRO — we can provide advice.”