Most people have heard about the San Andreas Fault. It’s the 800-mile-long monster that cleaves California from south to north, as two tectonic plates slowly grind against each other, threatening to produce big earthquakes.

Lesser known is the fact that the San Andreas comprises three major sections that can move independently. In all three, the plates are trying to move past each other in opposing directions, like two hands rubbing against each other. In the southern and the northern sections, the plates are locked much of the time—stuck together in a dangerous, immobile embrace. This causes stresses to build over years, decades or centuries. Finally a breaking point comes; the two sides lurch past each other violently, and there is an earthquake. However in the central section, which separates the other two, the plates slip past each other at a pleasant, steady 26 millimeters or so each year. This prevents stresses from building, and there are no big quakes. This is called aseismic creep.

At least that is the story most scientists have been telling so far. Now, a study of rocks drilled from nearly 2 miles under the surface suggests that the central section has hosted many major earthquakes, including some that could have been fairly recent. The study, which uses new chemical-analysis methods to gage the heating of rocks during prehistoric quakes, just appeared in the online edition of the journal Geology.

“This means we can get larger earthquakes on the central section than we thought,” said lead author Genevieve Coffey, who did the research as a graduate student at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “We should be aware that there is this potential, that it is not always just continuous creep.”

The threats of the San Andreas are legion. The northern section hosted the catastrophic 1906 San Francisco magnitude 7.9 earthquake, which killed 3,000 people and leveled much of the city. Also, the 1989 M6.9 Loma Prieta quake, which killed more than 60 and collapsed a major elevated freeway. The southern section caused the 1994 M6.7 Northridge earthquake near Los Angeles, also killing about 60 people. Many scientists believe it is building energy for a 1906-scale event.

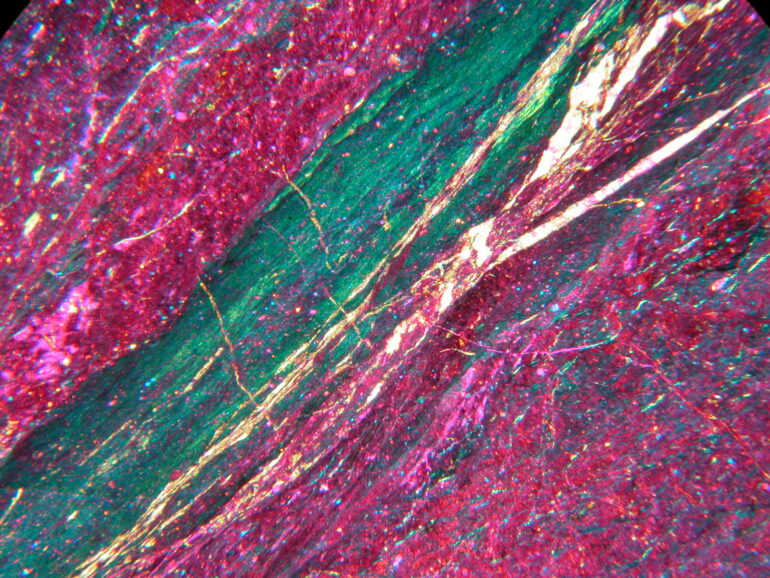

The central section, by contrast, appears harmless. Only one small area, near its southern terminus, is known to produce any real quakes. There, magnitude 6 events—not that dangerous by most standards—occur about every 20 years. Because of their regularity, scientists hoping to study clues that might signal a coming quake have set up a major observatory atop the fault near the city of Parkfield. It features a 3.2-kilometer-deep borehole from which rock cores have been