Continents reconfigure, oceans shift, and ice sheets thicken and thaw, but for the past 95 million years Earth’s engine for distributing ocean heat has remained remarkably consistent.

That’s one of the findings of a new, Yale-led study that tracks the evolution of Earth’s climate system with a novel approach for calculating the temperature difference between oceans in higher and lower latitudes. Using marine specimens from the ancient fossil record, the research offers a new way to gauge the accuracy of climate models.

The study appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“There are so many interlocking parts to climate science. What we’re doing here is trying to improve the foundations by testing some of the underlying dynamics of climate models that are used to predict future climate,” said Daniel Gaskell, a doctoral student at Yale and first author of the study.

Gaskell works in the lab of Pincelli Hull, a Yale assistant professor of Earth & planetary sciences and co-author of the new study.

One way to understand the global climate system is to envision it as a giant heat engine. That engine attempts to redistribute the sun’s heat from lower latitudes near the Equator to higher latitudes near the North and South poles. The latitudinal temperature gradient (LTG)—the difference in sea-surface temperatures between low and high latitudes—is an important measure of how well Earth’s heat engine is working.

The LTG is also an important factor in gauging how well climate models work to reconstruct the climate of Earth’s past and predict the climate of the future.

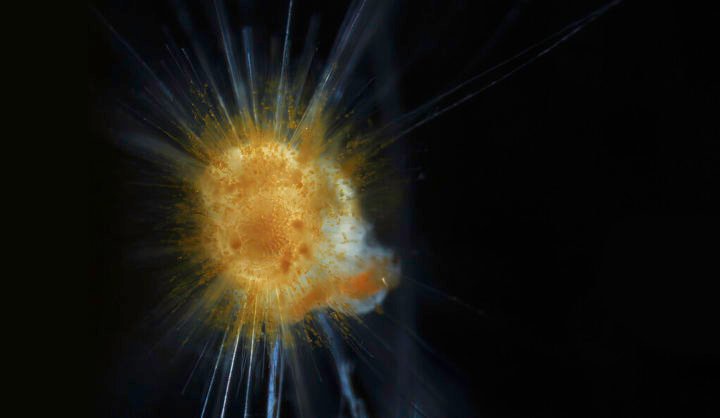

Foraminifera shells from a deep-sea sediment sample in the North Atlantic. © Daniel Gaskell, Yale University

Yet scientists say it has been difficult to nail down reliable surface temperature data to test models. There are relatively few geological or biochemical proxies for past temperatures, for one thing. For another, there can be large disagreements between those proxy temperature estimates and climate models.

But Gaskell, Hull, and their colleagues say they may have found a better approach to determining temperature gradients—and the proof is in plankton.

“The chemistry of plankton shells tells you so much,” Gaskell said. “Their shells carry an imprint of the seawater conditions at the time they were formed.”

The researchers used a combination of fossils from a single-celled organism called foraminifera to create a continuous, 95-million-year record of LTGs.

“Our results show that the behavior of this temperature difference (LTG) has been remarkably consistent over time,” said Hull. “When the climate warms, the temperature gradient goes down in almost a straight line, regardless of continental configuration or global ice volume.”

And how do the commonly used climate models hold up against this new LTG record? Quite well, the researchers say.

“The models work better than we thought they might,” Gaskell said. “It means we understand this aspect of the climate system pretty well and it implies that some of the more extreme scenarios are not as likely to happen.”

More information:

Daniel E. Gaskell et al, The latitudinal temperature gradient and its climate dependence as inferred from foraminiferal δ 18 O over the past 95 million years, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2111332119

Citation:

Core aspects of climate models are sound: The proof is in the plankton (2022, March 8)