Tomographic 3D printing is a revolutionary technology that uses light to create three-dimensional objects. A projector beams light at a rotating vial containing photocurable resin, and within seconds the desired shape forms inside the vial. The light projections needed to solidify specific 3D regions of the polymer are calculated using tomographic imaging concepts.

The technology was first demonstrated by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley and Lawrence Livermore National Labs in 2019, and a Swiss group at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in 2020. It is significantly faster than traditional 3D printing in layers, can print around existing objects, and does not require support structures.

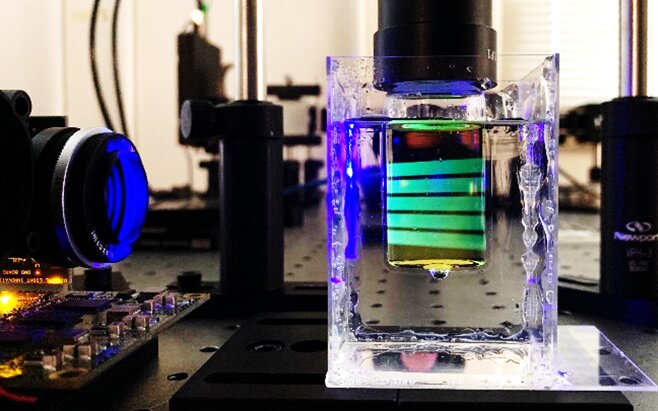

Though incredible, the technology can get messy in the lab. The vial’s round shape makes it refract rays like a lens. To counter this, experts use a rectangular index-matching bath that provides a flat surface for rays to pass through correctly. The vial of resin must be dipped in and out of the bath for each use—creating a slimy situation.

New equations and code cut technology loose

It was slimy, that is, until a student from the University of Waterloo joined the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) for a virtual co-op term in 2020. Kayley Ting, who is doing a bachelor of applied science (BASc) degree in biomedical engineering, worked with machine vision and 3D printing experts from the NRC’s Digital Technologies and Security and Disruptive Technologies Research Centres.

Together they developed a technology that computationally corrects for optical distortions. New equations compensate for the vial’s round shape and eliminate the need for the goopy, square bath, while still enabling the nearly instant production of precise polymer shapes using light.

The team also developed new code to program the printer so that it could produce complex objects and be easily used by non-experts. They recently published their new method and findings in Optics Express, an open-access scientific journal, and revealed a few dazzling shapes they produced.

Virtual co-op term generates real progress

Due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, Kayley could not access the lab in Ottawa where objects are printed. But that didn’t stop her from innovating at a distance. To print complex objects using STL files, Kayley wrote the code that imports the 3D object file, slices it, and converts 2D slices to the light projections that will be shone on the vial. Intensive computations are required at this step.

“While it used to take about an hour to process a print file, Kayley’s version of the code usually takes less than a minute to execute,” says Antony Orth, research officer from Digital Technologies and Kayley’s supervisor.

The progress made by Kayley during her virtual work term at the NRC will have practical applications in the future.

“Kayley also produced a simple user interface with buttons and menus that enables people to use the printer without knowing how to code. This is a huge deal for us as it will make the technology much more usable at the NRC and for others interested in tomographic 3D printing,” says Chantal Paquet, research officer from Security and Disruptive Technologies.

New materials help expand volumetric 3-D printing

More information:

Antony Orth et al. Correcting ray distortion in tomographic additive manufacturing, Optics Express (2021). DOI: 10.1364/OE.419795

Provided by

University of Waterloo

Citation:

Engineering student helps federal experts solve a messy 3D printing problem (2021, May 6)

retrieved 7 May 2021

from https://techxplore.com/news/2021-05-student-federal-experts-messy-3dprinting.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.