Imagine reading by the light of an exploded star, brighter than a full moon—it might be fun to think about, but this scene is the prelude to a disaster when the radiation devastates life as we know it. Killer cosmic rays from nearby supernovae could be the culprit behind at least one mass extinction event, researchers said, and finding certain radioactive isotopes in Earth’s rock record could confirm this scenario.

A new study led by University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign astronomy and physics professor Brian Fields explores the possibility that astronomical events were responsible for an extinction event 359 million years ago, at the boundary between the Devonian and Carboniferous periods.

The paper is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team concentrated on the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary because those rocks contain hundreds of thousands of generations of plant spores that appear to be sunburnt by ultraviolet light—evidence of a long-lasting ozone-depletion event.

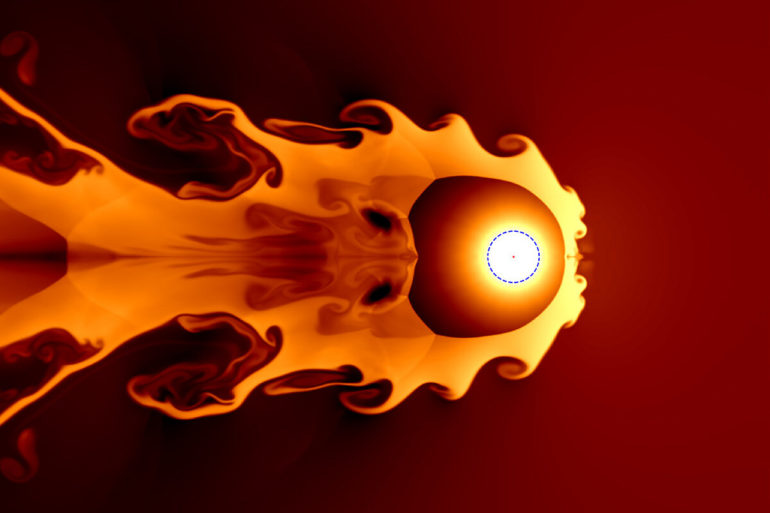

“Earth-based catastrophes such as large-scale volcanism and global warming can destroy the ozone layer, too, but evidence for those is inconclusive for the time interval in question,” Fields said. “Instead, we propose that one or more supernova explosions, about 65 light-years away from Earth, could have been responsible for the protracted loss of ozone.”

“To put this into perspective, one of the closest supernova threats today is from the star Betelgeuse, which is over 600 light-years away and well outside of the kill distance of 25…