Vast filaments of intergalactic gas are the highways along which galaxies are hurtling towards a certain collision.

In new, extremely detailed images of an enormous cluster of galaxies, astronomers have identified that the cluster is moving along a vast thread of gas, inexorably drawn by gravity towards two other clusters of galaxies.

It’s not the first such impending cosmic smash-up that we’ve seen, but it does seem to confirm the theory that these filaments of gas are “matter roads”, guiding galaxy cluster mergers.

The new research has been submitted to Astronomy & Astrophysics and is available on preprint server arXiv.

The filament itself, spanning 50 million light-years and faintly glowing in X-rays, was identified and described last year. Such filaments make up the strands of the cosmic web; they clumped together under gravity in the Universe’s early stages, and they span vast intergalactic distances between galaxies and clusters of galaxies.

Filaments like these can tell us a lot about the Universe, such as how it formed and continues to evolve, where dark matter is concentrated (the mysterious invisible substance responsible for extra gravity in the Universe), and where we can find normal matter, too.

But the threads of diffuse gas are very faint, compared to all the very bright stuff out there, like stars and galaxies. We’ve only just started finding them. So astronomers were very interested in this vast cosmic filament, and were taking a closer look.

Specifically, one of the things they were looking at was a feature known as the Northern Clump, a cluster of galaxies found in the filament.

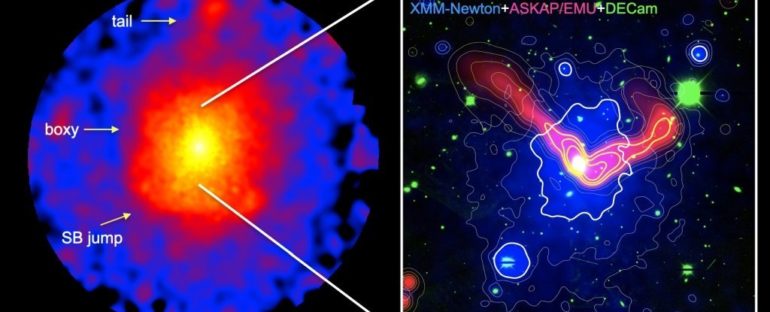

By combining data from a number of X-ray and radio telescopes, the researchers were able to identify a galaxy at the centre of the Northern Clump, with an active supermassive black hole at its center.

That the supermassive black hole is active, devouring material swirling around it in a dense disc, is key. As material from this disc feeds into the black hole, some is channeled around the outside along magnetic field lines, researchers think, where it is launched from the poles into space at speeds approaching the speed of light.

These jets of material can travel tremendous distances into space, which allows astronomers to make observations about the intergalactic environment. And this proved to be the case with the galaxy at the heart of the Northern Clump.

Its jets, according to astrophysicist Angie Veronica of the University of Bonn in Germany, are streaming away as the Northern Clump hurtles through space “like the braids of a running girl”.

This, the researchers believe, suggests that the Northern Clump is traveling at great velocity along the filament, towards two other galaxy clusters that are also aligned along the filament – Abell 3391 and Abell 3395.

We can’t see that motion, of course – it’s simply occurring on scales that are too vast and too distant – but we can see its effects.

“We are currently interpreting this observation such that the Northern Clump is losing matter as it travels,” explained astrophysicist Thomas Reiprich of the University of Bonn. “However, it could also be that even smaller clumps of matter in the thread are falling toward the Northern Clump.”

Eventually, the clusters will meet and merge, forming an even larger cluster of galaxies – a cosmic pile-up on a mind-blowing scale. This scenario matches simulations performed by a separate team of astronomers.

It’s thought that filaments of the cosmic web are responsible for feeding star-forming material into nodes, where it can form galaxies and clusters of galaxies. Without the cosmic web, the Universe as we know it may not even exist. So understanding how and why it works is fundamental to cosmology.

The new findings are consistent with current theory about the cosmic web, including the idea that dark matter gravitationally binds the filaments. And they’re leading us ever closer into understanding how everything in the Universe is connected.

The research has been submitted to Astronomy & Astrophysics and is available on arXiv.