After four years of digging for fossils in a churchyard in York, Pennsylvania, amateur paleontologist Chris Haefner made an intriguing find. “I knew it was worth keeping,” he said. He posted his discovery on Facebook.

I spotted his post, and realized it was a major discovery: I study fossil invertebrates at the Spanish Research Council. When I contacted Haefner, he agreed to donate the fossil to London’s Natural History Museum.

Working with colleagues in the U.S. and U.K., we determined that this was a 510 million-year-old relative of today’s starfish and sea urchins. It is highly unique, new to science, and has only a partial skeleton. We named it Yorkicystis haefneri, after its finder.

Yorkicystis has revealed new information about how early life was evolving on Earth at a time when most of today’s animal groups first appeared.

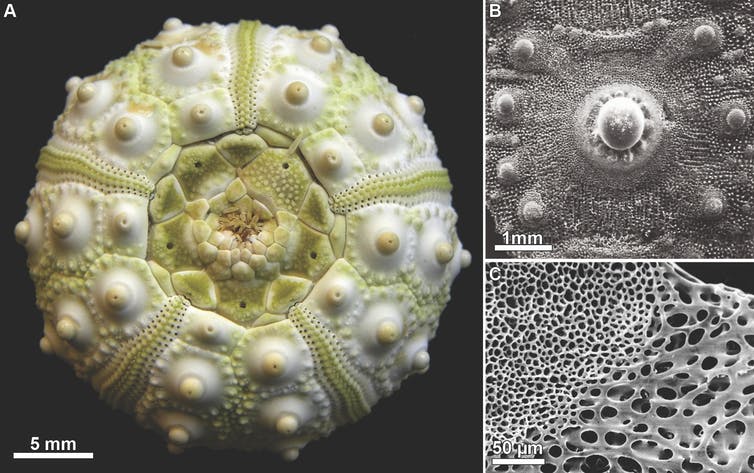

Sea urchins are among Yorkicystis‘ surviving relatives.

Samuel Zamora, CC BY-ND

The Cambrian explosion

Yorkicystis lived during the “Cambrian explosion,” 539 million to 485 million years ago. Before this time, bacteria and other simple microscopic organisms lived alongside Ediacaran fauna, mysterious, soft-bodied creatures that scientists know little about.

The Cambrian brought a huge proliferation of species that emerged from the seas. They included groups of organisms that would eventually dominate the planet and representatives of most of today’s animal groups.

Within a few million years, complex animals with skeletons and hard shells appeared. Why this happened remains unclear, but a major change in ocean chemistry, with a higher concentration of calcium carbonate, likely played a key role.

Echinoderms weren’t the first of these found in the geological record. Brachiopods – marine animals that lived protected within seashells – predated them. So did arthropods, a group that had well-formed calcite exoskeletons, including trilobites.

For context, dinosaurs appeared 294 million years after the dawn of the Cambrian.

The first echinoderms

There are more that 30,000 extinct echinoderm species, but they are very rare in places with exceptional Cambrian preservation, like the Burgess Shale in Canada and Chengjiang in China.

Some of the first primitive echinoderms were quite different from their present-day relatives, which have five arms extending from the center of their bodies, a structure called “pentamerous symmetry.”

Cambrian echinoderms had a wide range of body structures. Eocrinoids had vase-shaped bodies protected by geometrically patterned plates and a number of armlike structures. Helicoplacoids, shaped like fat cigars, were plated in calcite armor with a “mouth” that spiraled around its body. Blastoid species took various shapes, often resembling exotic flowers.

The Edrioasteroidea looked similar to today’s sea star, and with five arms that radiated from its mouth, it is the organism that Yorkicystis haefneri…