Ground squirrels spend the end of summer gorging on food, preparing for hibernation. They need to store a lot of energy as fat, which becomes their primary fuel source underground in their hibernation burrows all winter long.

While hibernating, ground squirrels enter a state called torpor. Their metabolism drops to as low as just 1% of summer levels and their body temperature can plummet to close to freezing. Torpor greatly reduces how much energy the animal needs to stay alive until springtime.

That long fast comes with a downside: no new input of protein, which is crucial to maintain the body’s tissues and organs. This is a particular problem for muscles. In people, long periods of inactivity, like prolonged bed rest, lead to muscle wasting. But muscle wasting is minimal in hibernating animals. Despite as much as six to nine months of inactivity and no protein intake, they preserve muscle mass and performance remarkably well – a very handy adaptation that helps ensure a successful breeding season come spring.

How do hibernators pull this off? It’s been a real head-scratcher for hibernation biologists for decades. Our research team tackled this question by investigating how hibernating animals might be getting a major assist from the microbes that live in their guts.

The 13-lined ground squirrel shows minimal signs of muscle wasting, even after hibernating for up to six months.

Robert Streiffer, CC BY

A nitrogen-recycling system

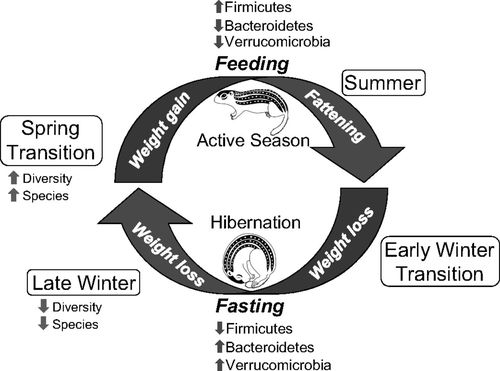

We knew from previous research that a hibernator’s gastrointestinal system undergoes dramatic changes in its structure and function from summer feeding to winter fasting. And it’s not only the animals who are fasting all winter long – their gut microbes are, too. Along with our microbiology collaborators, we figured out that winter fasting changes the gut microbiome quite a bit.

And then we wondered … could gut microbes play a functional role in the process of hibernation itself? Could certain bacteria help keep muscle and other tissues working when the mostly immobile animals aren’t eating?

Microbes in their guts help ruminants, including cows, hold on to the nitrogen they need to build proteins.

Lemanieh/ iStock via Getty Images Plus

Biologists had previously identified a clever trick in ruminant animals, such as cattle, that helps them survive times when protein intake in the diet is low or protein needs are especially high, such as during pregnancy. A process called urea nitrogen salvage allows the animal to recoup nitrogen – a critical ingredient for building protein – that would otherwise be excreted in urine as the waste product urea. Instead, the urea’s nitrogen is retained in the body and used to make amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

This salvage operation depends on the chemical breakdown of urea molecules to release their nitrogen. But here’s the kicker: Chemical breakdown of urea…