When one family member looks out the window at sidewalks and green space and the other sees a multilane highway and power lines, the differences may contribute to more than just sibling rivalry. A new study by University of Maryland public health researchers has shown that those neighborhood characteristics correlate with different health outcomes.

Quynh and Thu Nguyen—UMD associate professors of epidemiology and biostatistics and twin sisters—used Google Street View to combine neighborhood walkability and aesthetic data with health information from the Utah Population Database, a unique resource that interlinks family histories and demographic and medical statistics.

This allowed the research team, which also included experts from the University of Utah and the University of Alabama, to analyze how the built environment correlates with health among siblings and twins.

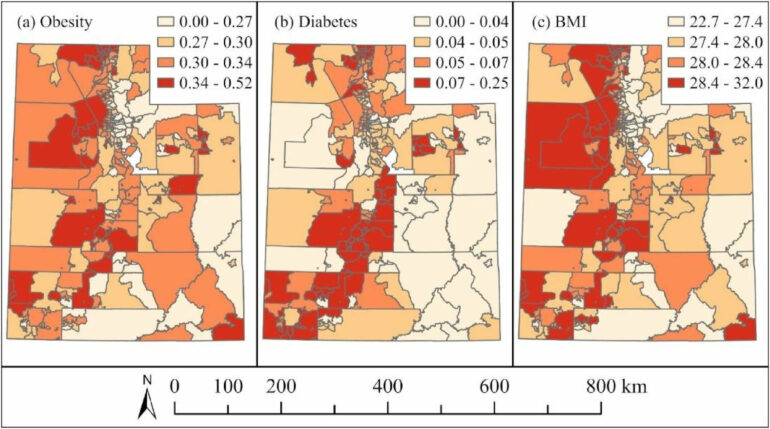

The results of their study were published in the June issue of SSM—Population Health. After examining records from nearly 2 million people, including 1 million siblings and 14,000 identical and fraternal twins, the team found that across all three samples, positive built environment characteristics were associated with 15%–20% reductions in obesity and diabetes rates.

“Neighborhoods research is especially complicated because it’s often observational. You can only observe where people live; you often don’t get a chance to randomize them to their residential neighborhoods,” said Quynh Nguyen, the study’s first author. “Using siblings, we can try to control for shared family characteristics and even shared genetics.”

The researchers collected nearly 1.4 million Google Street View images from all the main streets across Utah, then used computer vision models to extract neighborhood characteristics like greenery, sidewalks and non-single-family homes—indicators of walkability and mixed land use—from those images. They merged that data with health stats, including diabetes diagnoses and obesity incidence, from the state’s population database.

The new study builds on past research the Nguyens and others have conducted using Google Street View, which has similarly found that neighborhood features like green streets, sidewalks and crosswalks encourage more physical activity. Additional studies with different designs can create a better case for causality, Nguyen said.

“People will counter by saying, ‘It’s not the neighborhoods that matter; it’s actually the composition of neighborhood residents,'” she said. “It’s a complex mixture of things, so to kind of tease out which contributions are place-based and which are individual-level effects or even family-level effects is important.”

Future studies could also shine a light on how factors like income inequality and unequal access to desirable neighborhoods—along with modifiable built environment features—impact health.

“An even larger picture would be, how do people get sorted into different neighborhoods?” Thu Nguyen said. “What are the different historical policies, current policies, discrimination biases that constrain people’s movements to different neighborhoods?”

Next, the Nguyens will analyze Google Street View images from 2007–22 in Washington, D.C., to see how changes to the environment, including factors like gentrification and segregation, correspond with changes to neighborhood population health over time. They hope the longitudinal study will add to and build from the correlations they’ve found so far.

More information:

Quynh C. Nguyen et al, Neighborhood built environment, obesity, and diabetes: A Utah siblings study, SSM – Population Health (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2024.101670

Provided by

University of Maryland

Citation:

Walkability in neighborhoods linked to health, study of siblings shows (2024, May 24)