When the first humans moved out of Africa, they carried their gut microbes with them. Turns out, these microbes also evolved along with them.

The human gut microbiome is made up of hundreds to thousands of species of bacteria and archaea. Within a given species of microbe, different strains carry different genes that can affect your health and the diseases you’re susceptible to.

There is pronounced variation in the microbial composition and diversity of the gut microbiome between people living in different countries around the world. Although researchers are starting to understand what factors affect microbiome composition, such as diet, there is still limited understanding on why different groups have different strains of the same species of microbes in their guts.

We are researchers who study microbial evolution and microbiomes. Our recently published study found that not only did microbes diversify with their early modern human hosts as they traveled across the globe, they followed human evolution by restricting themselves to life in the gut.

The gut microbiome plays a key role in many areas of your health.

Microbes share evolutionary history with humans

We hypothesized that as humans fanned out across the globe and diversified genetically, so did the microbial species in their guts. In other words, gut microbes and their human hosts “codiversified” and evolved together – just as human beings diversified so that people in Asia look different from people in Europe, so too did their microbiomes.

To assess this, we needed to pair human genome and microbiome data from people around the world. However, data sets that provided both the microbiome data and genome information for individuals were limited when we started this study. Most publicly available data was from North America and Western Europe, and we needed data that was more representative of populations around the world.

So our research team used existing data from Cameroon, South Korea and the United Kingdom, and additionally recruited mothers and their young children in Gabon, Vietnam and Germany. We collected saliva samples from the adults to ascertain their genotype, or genetic characteristics, and fecal samples to sequence the genomes of their gut microbes.

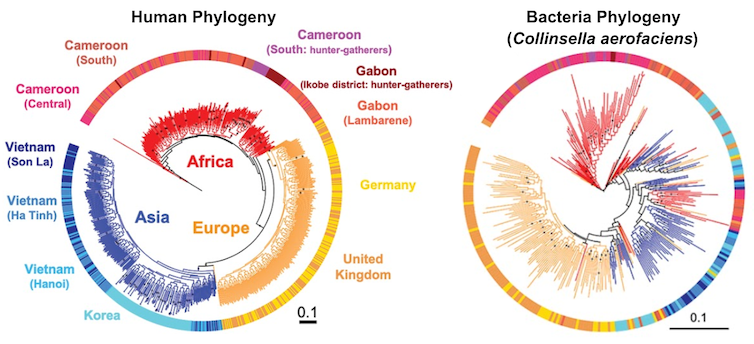

For our analysis, we used data from 839 adults and 386 children. To assess the evolutionary histories of humans and gut microbes, we created phylogenetic trees for each person and as well as for 59 strains of the most commonly shared microbial species.

When we compared the human trees to the microbial trees, we discovered a gradient of how well they matched. Some bacterial trees didn’t match the human trees at all, while some matched very well, indicating that these species codiversified with humans. Some microbial species, in fact, have been along for the evolutionary ride for over hundreds of thousands of years.

…