The best graduation speeches dispense wisdom you find yourself returning to long after the graduation tassels are turned. Take the feel-good life advice in Baz Luhrmann’s song to a class that graduated 25 years ago. Only on a recent relisten did I realize it also captures one of the research-based strategies I teach for avoiding communication that backfires.

The tip is hiding in plain sight in the song’s title, “Everybody’s Free (to Wear Sunscreen).” Communication aimed at promoting a certain behavior can have the opposite effect when the message is perceived as a threat to individual autonomy.

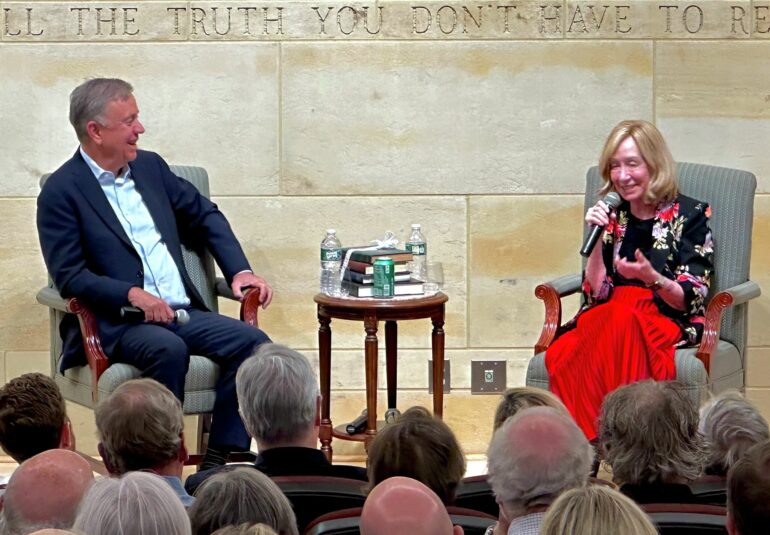

Here, have some sunscreen … or don’t, it’s your call.

Catherine Falls Commercial/Moment via Getty Images

Health campaigns frequently use strongly worded messages that end up backfiring. For example, strongly worded messages promoting dental flossing made people angry and more likely to resist flossing their teeth. Coercive alcohol prevention messages, with language like “any reasonable person must acknowledge these conclusions,” instead increased alcohol consumption. In contrast, the wording of the title “Everybody’s Free (to Wear Sunscreen)” is less likely to backfire by emphasizing liberty of choice.

Research reveals lots of reasons why well-meaning attempts to inform, persuade or correct misinformation go awry. Despite the ubiquity of backfires, formal instruction about why they happen and how to avoid them is rare. The omission inspired my new book, “Beyond the Sage on the Stage: Communicating Science and Contemporary Issues Effectively,” which translates scholarship from across disciplines into practical strategies that anyone can use to improve communication.

When new info challenges your identity

Backfires are often a response to communication of unwelcome information.

In addition to threats to autonomy, information can be unwelcome because it appears to conflict with how you think about yourself. Consider a study that asked people to read a message about genetically modified foods. Participants for whom purity, health and conscientiousness of their diet was an important part of how they defined themselves had more negative attitudes after reading a message intended to refute their views about GM food. Those who did not have a strong dietary self-concept did not react negatively to the message.

The same resistance can rise up when you’re confronted with something counter to the beliefs of a group you feel a strong affiliation with. Emotional and identity attachment to a group such as a political party can cause people to subjugate their own values to align with the group, a phenomenon called cultural cognition. Reactions to messages about climate change often exemplify this phenomenon.

Against the backdrop of protests and an impending election, communication breakdowns are increasingly blamed on political polarization, with more than a hint of fatalism. But the…