A previously unknown form of a severe and progressive neurodegenerative disease that usually affects older adults has been identified in children as young as three years of age.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rare neurological disorder where motor neuron degeneration leads to serious impairments in voluntary muscle movement.

The condition, which causes increasing weakness in muscles throughout the body, makes walking, talking, and eventually even breathing a struggle, leading to death in most patients within a few years of symptoms showing.

The majority of ALS cases emerge in people aged between 55 and 75, and most cases are considered sporadic, with the cause ultimately remaining unknown.

For some people, however, the disease presents very differently. In a minority of cases, genetics appears to play a causative role – and sometimes the disease shows up in much younger people.

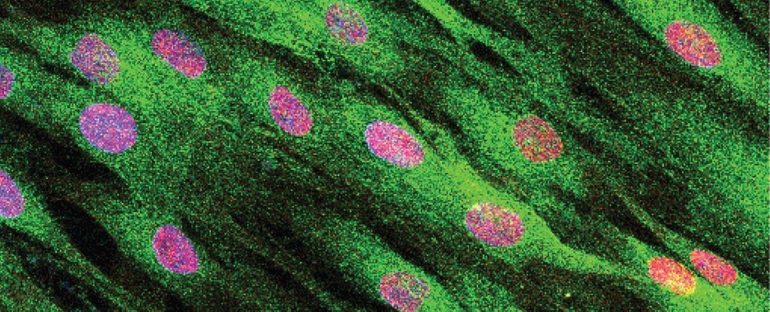

(NIH/NINDS)

Above: Study authors Carsten Bönnemann (right) and Payam Mohassel (left) assess patient Claudia Digregorio.

In a new study, scientists found both these rarer manifestations of the disease coinciding, discovering an unusual set of mutations linked to a distinct form of genetic ALS in children, whose mysterious muscle-wasting illnesses had puzzled their doctors for years.

In the most publicized of these heartbreaking cases, an Italian teenager called Claudia Digregorio ended up meeting with the Pope after her unidentified degenerative illness caught attention on YouTube.

At the same time, scientists at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in Bethesda, Maryland began investigating Claudia’s disease, hoping to find answers for the underlying cause of her condition.

Now, in an international investigation of 10 such young patients, many of whom started experiencing ALS-like symptoms in early childhood, researchers have identified a genetic basis for this rare sub-type of an already rare disease.

“These young patients had many of the upper and lower motor neuron problems that are indicative of ALS,” says neurologist Payam Mohassel from the National Institutes of Health.

“What made these cases unique was the early age of onset and the slower progression of symptoms. This made us wonder what was underlying this distinct form of ALS.”

The answer appears to lie in a set of mutations in a gene called SPTLC1, which encodes a protein that acts as a catalyst in the production of fatty molecules called sphingolipids.

The DNA of the 10 young patients in the study revealed mutations in the SPTLC1 gene, with four of the patients (all from one family) inheriting their variations from one of their parents, while the other six, unrelated patients appeared to show random de novo mutations (present for the first time in a family member) in the gene.

In either case, the mutations are problematic, leading to excessive productions of sphingolipids, linked to abnormally high levels of an enzyme that helps make the lipids, called serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT).

“Our results suggest that these ALS patients are essentially living without a brake on SPT activity,” says biochemist Teresa M. Dunn from Uniformed Services University.

“SPT is controlled by a feedback loop… The mutations these patients carry essentially short-circuit this feedback loop.”

Abnormalities in SPT activity due to mutations in the SPTLC1 gene have previously been linked to neurodegeneration in another disease, called Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy (HSAN1), although the pathological mechanism appears to be different.

In HSAN1, SPTLC1 mutations produce harmful sphingolipids; in the present study, the SPTLC1 mutations found produced abnormal levels of non-harmful sphingolipids, by inhibiting a protein called ORMDL from regulating SPT activity.

In turn, the oversupply of sphingolipids accumulates in human motor neurons, leading to the early onset form of motor neuron disease, which the team characterizes as ‘childhood-onset ALS’.

Fortunately, there could be a way to stop this from happening, with the researchers figuring out a way to turn off the mutant SPTLC1 gene by using small interfering RNA (siRNA): RNA molecules that specifically target the mutant allele and inhibit the overactive SPT production.

While the experiment has only been tested in the patients’ cells for now – not yet on the patients themselves – the breakthrough points to a future where treatments could be possible, when children might hopefully be spared the worst of this debilitating and despairing disease.

“These preliminary results suggest that we may be able to use a precision gene silencing strategy to treat patients with this type of ALS,” says NINDS senior investigator Carsten Bönnemann.

“Our ultimate goal is to translate these ideas into effective treatments for our patients who currently have no therapeutic options.”

The findings are reported in Nature Medicine.