Perched about 325 feet (100 meters) up the slopes of the Prealps in southern France, a humble rock shelter looks out over the Rhône River Valley. It’s a strategic point on the landscape, as here the Rhône flows through a narrows between two mountain ranges. For millennia, inhabitants of the rock shelter would have had commanding views of herds of animals migrating between the Mediterranean region and the plains of northern Europe, today replaced by TGV trains and up to 180,000 vehicles per day on one of the busiest highways on the continent.

Grotte Mandrin is somewhat camouflaged as a rock outcropping when viewed from a distance.

Ludovic Slimak

The site, recognized in the 1960s and named Grotte Mandrin after French folk hero Louis Mandrin, has been a valued location for over 100,000 years. The stone artifacts and animal bones left behind by ancient hunter-gatherers from the Paleolithic period were quickly covered by the glacial dust that blew from the north on the famous mistral winds, keeping the remains well preserved.

View of the excavations at the entrance of Grotte Mandrin.

Ludovic Slimak

Since 1990, our research team has been carefully investigating the uppermost 10 feet (3 meters) of sediment on the cave floor. Based on artifacts and tooth fossils, we believe that Mandrin rewrites the consensus story about when modern humans first made their way to Europe.

Human origins researchers have generally agreed that between 300,000 and 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals and their ancestors occupied Europe. From time to time during that period, they had contact with modern humans in the Levant and parts of Asia. Then around 48,000 to 45,000 years ago, modern humans – essentially us – expanded throughout the rest of the world, and Neanderthals and all other archaic humans disappeared.

In the journal Science Advances, we describe our discovery of evidence that modern humans lived 54,000 years ago at Mandrin. That’s some 10 millennia earlier than our species was previously thought to be in Europe and over a thousand miles west (1,700 kilometers) from the next-oldest known site, in Bulgaria. And fascinatingly, Neanderthals appear to have used the cave both before and after the modern human occupation.

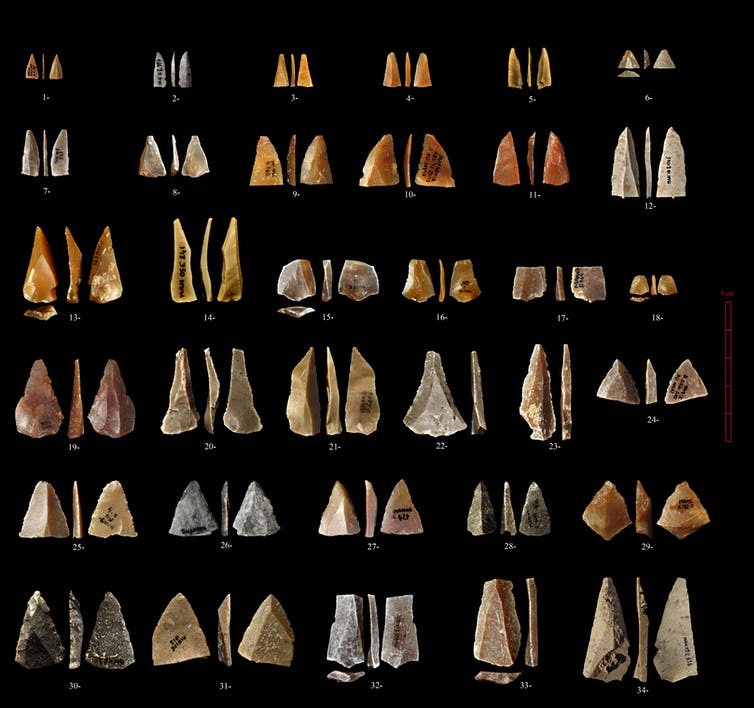

Clues from tiny stone points and a tooth

The first curious finding to emerge during the initial decade of Grotte Mandrin excavations were 1,500 tiny triangular stone points identified in what we labeled Layer E. Some less than half an inch (1 cm) in length, these points resemble arrowheads. They have no technological precursors or successors in the 11 surrounding archaeological layers of Neanderthal artifacts in the cave.