Although the ground beneath our feet feels solid and reassuring (most of the time), nothing in this Universe lasts forever.

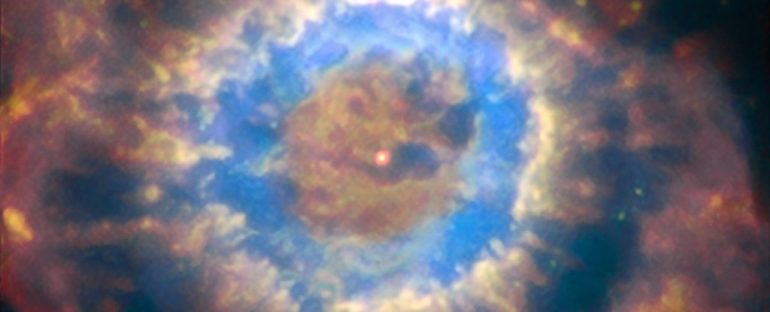

One day, our Sun will die, ejecting a large proportion of its mass before its core shrinks down into a white dwarf, gradually leaking heat until it’s nothing more than a cold, dark, dead lump of rock, a thousand trillion years later.

But the rest of the Solar System will be long gone by then. According to new simulations, it will take just 100 billion years for any remaining planets to skedaddle off across the galaxy, leaving the dying Sun far behind.

Astronomers and physicists have been trying to puzzle out the ultimate fate of the Solar System for at least hundreds of years.

“Understanding the long-term dynamical stability of the solar system constitutes one of the oldest pursuits of astrophysics, tracing back to Newton himself, who speculated that mutual interactions between planets would eventually drive the system unstable,” wrote astronomers Jon Zink of the University of California, Los Angeles, Konstantin Batygin of Caltech and Fred Adams of the University of Michigan in their new paper.

But that’s a lot trickier than it might seem. The greater the number of bodies that are involved in a dynamical system, interacting with each other, the more complicated that system grows and the harder it is to predict. This is called the N-body problem.

Because of this complexity, it’s impossible to make deterministic predictions of the orbits of Solar System objects past certain timescales. Beyond about five to 10 million years, certainty flies right out the window.

But, if we can figure out what’s going to happen to our Solar System, that will tell us something about how the Universe might evolve, on timescales far longer than its current age of 13.8 billion years.

In 1999, astronomers predicted that the Solar System would slowly fall apart over a period of at least a billion billion – that’s 10^18, or a quintillion – years. That’s how long it would take, they calculated, for orbital resonances from Jupiter and Saturn to decouple Uranus.

According to Zink’s team, though, this calculation left out some important influences that could disrupt the Solar System sooner.

Firstly, there’s the Sun.

In about 5 billion years, as it dies, the Sun will swell up into a red giant, engulfing Mercury, Venus and Earth. Then it will eject nearly half its mass, blown away into space on stellar winds; the remaining white dwarf will be around just 54 percent of the current solar mass.

This mass loss will loosen the Sun’s gravitational grip on the remaining planets, Mars and the outer gas and ice giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Secondly, as the Solar System orbits the galactic centre, other stars ought to come close enough to perturb the planets’ orbits, around once every 23 million years.

“By accounting for stellar mass loss and the inflation of the outer planet orbits, these encounters will become more influential,” the researchers wrote.

“Given enough time, some of these flybys will come close enough to disassociate – or destabilise – the remaining planets.”

With these additional influences accounted for in their calculations, the team ran 10 N-body simulations for the outer planets (leaving out Mars to save on computation costs, since its influence should be negligible), using the powerful Shared Hoffman2 Cluster. These simulations were split into two phases: up to the end of the Sun’s mass loss, and the phase that comes after.

Although 10 simulations isn’t a strong statistical sample, the team found that a similar scenario played out each time.

After the Sun completes its evolution into a white dwarf, the outer planets have a larger orbit, but still remain relatively stable. Jupiter and Saturn, however, become captured in a stable 5:2 resonance – for every five times Jupiter orbits the Sun, Saturn orbits twice (that eventual resonance has been proposed many times, not least by Isaac Newton himself).

These expanded orbits, as well as characteristics of the planetary resonance, makes the system more susceptible to perturbations by passing stars.

After 30 billion years, such stellar perturbations jangle those stable orbits into chaotic ones, resulting in rapid planet loss. All but one planet escape their orbits, fleeing off into the galaxy as rogue planets.

That last, lonely planet sticks around for another 50 billion years, but its fate is sealed. Eventually, it, too, is knocked loose by the gravitational influence of passing stars. Ultimately, by 100 billion years after the Sun turns into a white dwarf, the Solar System is no more.

That’s a significantly shorter timeframe than that proposed in 1999. And, the researchers carefully note, it’s contingent on current observations of the local galactic environment, and stellar flyby estimates, both of which may change. So it’s by no means engraved in stone.

Even if estimates of the timeline of the Solar System’s demise do change, however, it’s still many billions of years away. The likelihood of humanity surviving long enough to see it is slim.

Sleep tight!

The research has been published in The Astronomical Journal.