A previously unknown mechanism of active matter self-organization essential for bacterial cell division follows the motto “dying to align”: Misaligned filaments “die” spontaneously to form a ring structure at the center of the dividing cell. The study, led by the Šarić group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), was published in Nature Physics. The work could find applications in developing synthetic self-healing materials.

How does matter, lifeless by definition, self-organize and make us alive? One of the hallmarks of life, self-organization, is the spontaneous formation and breakdown of biological active matter. However, while molecules constantly fall in and out of life, one may ask how they “know” where, when, and how to assemble, and when to stop and fall apart.

Researchers around Professor Anđela Šarić and Ph.D. student Christian Vanhille Campos at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) address these questions in the context of bacterial cell division. They developed a computational model for the assembly of a protein called FtsZ, an example of active matter.

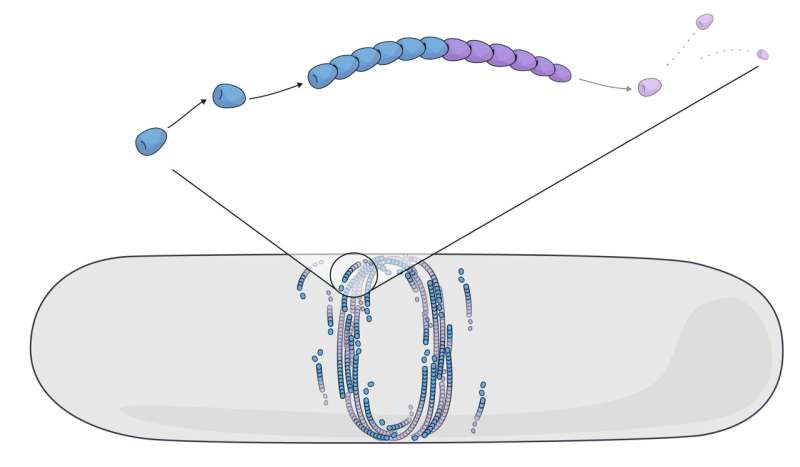

During cell division, FtsZ self-assembles into a ring structure at the center of the dividing bacterial cell. This FtsZ ring–called the bacterial division ring–was shown to help form a new “wall” that separates the daughter cells. However, essential physical aspects of FtsZ self-assembly have not been explained to this day.

Now, computational modelers from the Šarić group team up with experimentalists from Séamus Holden’s group at The University of Warwick, UK, and Martin Loose’s group at ISTA to reveal an unexpected self-assembly mechanism. Their computational work demonstrates how misaligned FtsZ filaments react when they hit an obstacle.

By “dying” and re-assembling, they favor the formation of the bacterial division ring, a well-aligned filamentous structure. These findings could have applications in the development of synthetic self-healing materials.

Treadmilling, the adaptive power of molecular turnover

FtsZ forms protein filaments that self-assemble by growing and shrinking in a continuous turnover. This process, called “treadmilling,” is the constant addition and removal of subunits at opposite filament ends. Several proteins have been shown to treadmill in multiple life forms—such as bacteria, animals, or plants.

Scientists have previously thought of treadmilling as a form of self-propulsion and modeled it as filaments that move forward. However, such models fail to capture the constant turnover of subunits and overestimate the forces generated by the filaments’ assembly. Thus, Anđela Šarić and her team set out to model how FtsZ subunits interact and spontaneously form filaments by treadmilling.

“Everything in our cells is in constant turnover. Thus, we need to start thinking of biological active matter from the prism of molecular turnover and in a way that adapts to the outside environment,” says Šarić.

Mortal filaments: Dying to align

What they found was striking. In contrast to self-propelled assemblies that push the surrounding molecules and create a “bump” felt at long molecular distances, they saw that misaligned FtsZ filaments started “dying” when they hit an obstacle.

“Active matter made up of mortal filaments does not take misalignment lightly. When a filament grows and collides with obstacles, it dissolves and dies,” says the first author Vanhille Campos.

Šarić adds, “Our model demonstrates that treadmilling assemblies lead to local healing of the active material. When misaligned filaments die, they contribute to a better overall assembly.”

By incorporating the cell geometry and filament curvature into their model, they showed how the death of misaligned FtsZ filaments helped form the bacterial division ring.

Theory-driven research, confirmed by collaborations with experimentalists

Driven by the physical theories of molecular interactions, Šarić and her team soon made two independent encounters with experimental groups that helped confirm their results. At a diverse and multidisciplinary conference called “Physics Meets Biology,” they met Holden, who worked on imaging bacterial ring formation in live cells.

At this meeting, Holden presented exciting experimental data showing that the death and birth of FtsZ filaments were essential for the formation of the division ring. This suggested that treadmilling had a crucial role in this process.

“Satisfyingly, we found that FtsZ rings in our simulations behaved in the same way as the Bacillus subtilis division rings that Holden’s team imaged,” says Vanhille Campos.

In a similar strike of luck, relocating from University College London to ISTA allowed Šarić and her group to team up with Martin Loose, who had been working on assembling FtsZ filaments in a controlled experimental setup in vitro. They saw that the in vitro results closely matched the simulations and further confirmed the team’s computational results.

Underlining the cooperation spirit and synergy between the three groups, Šarić says, “We are all stepping outside our usual research fields and going beyond what we normally do. We openly discuss and share data, views, and knowledge, which allows us to answer questions we cannot tackle separately.”

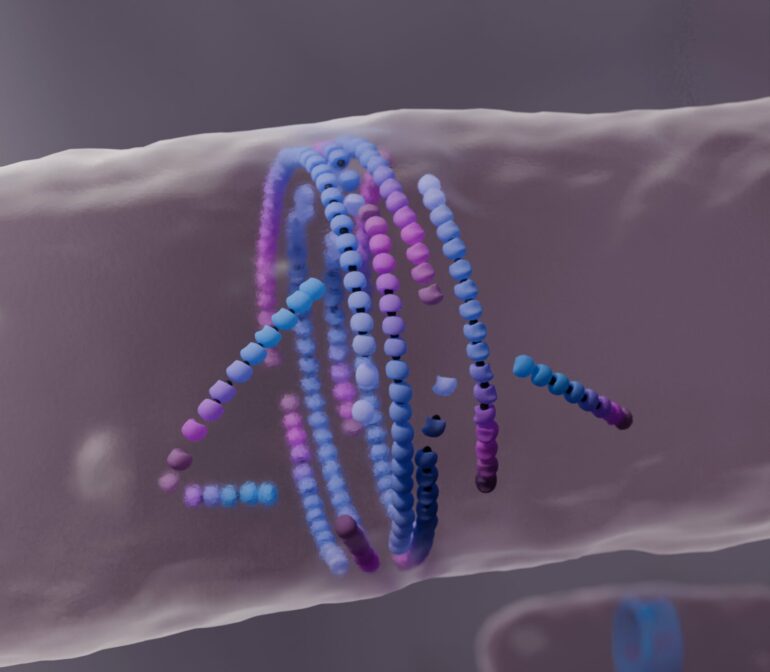

Simulating FtsZ filament self-organization by treadmilling. Modeling the treadmilling of FtsZ filaments in a bacterial cell shows how the bacterial division ring forms. © Claudia Flandoli

Toward synthetic self-healing materials

Energy-driven self-organization of matter is a fundamental process in physics. The team led by Šarić now suggests that FtsZ filaments are a different type of active matter that invests energy in turnover rather than motility.

“In my group, we ask how to create living matter from non-living material that looks living. Thus, our present work could facilitate the creation of synthetic self-healing materials or synthetic cells,” says Šarić.

As a next step, Šarić and her team seek to model how the bacterial division ring helps build a wall that will divide the cell into two.

More information:

Self-organisation of mortal filaments and its role in bacterial division ring formation, Nature Physics (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41567-024-02597-8

Provided by

Institute of Science and Technology Austria

Citation:

Align or die: Revealing unknown mechanism essential for bacterial cell division (2024, August 12)