To harness the forces that power the sun to produce substantial clean energy on Earth, researchers heat fuel to such a high temperature that atoms melt into electrons and nuclei to form a hot, gaseous soup called plasma. Roughly 20 times the temperature of the sun’s core at 200 million degrees Celsius, the plasma can rip through any material on Earth, so it must be confined by magnetic fields—but it can only be controlled for short periods. Researchers have been able to exert this control for decades, without understanding the precise physics of how it works. Now, in a first step to prolonged control, researchers at Japan’s National Institute for Fusion Science have discovered that the underlying mechanism mirrors the unlikely biological predator-prey model.

Their report was made available online Feb. 1, ahead of publication in Physical Review Letters.

“It is necessary to reduce the plasma heat load—especially at the diverter, where the heat load becomes most significant—while maintaining the core plasma performance,” said paper author Tatsuya Kobayashi, National Institute for Fusion Science in the National Institutes of Natural Sciences and the Graduate School of Advanced Studies, explaining the diverter acts as the LHD’s waste removal system during operation.

To alleviate the heat load, the researchers can induce detachment plasma by forcing the plasma’s constituents to recombine and dissipate energy in the form of light in front of the LHD’s diverter.

“In the present experiments, the detachment plasma is produced by applying an external magnetic field perturbation with supplementary magnetic coils,” Kobayashi said. “By doing so, a magnetic field structure embedded in the main plasma body, called the magnetic island, appears, enhancing the peripheral radiation energy losses and pushing the plasma to the detachment state. While the operation condition has been experimentally determined, the background physics was not fully understood yet.”

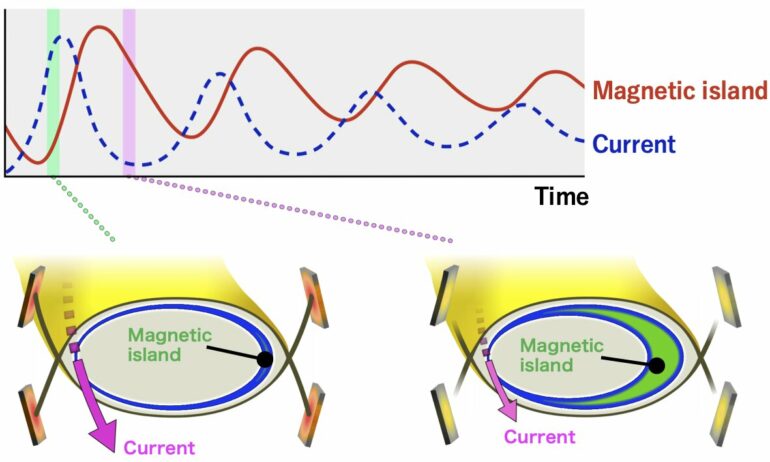

Through further analysis, the researchers found that the magnetic island and the point at which the plasma transitions between detachment and attachment phases oscillated in a self-sustained undulation. The parameters of the plasma current at the diverter directly influenced the width of the magnetic island, which then factored into the changing the plasma parameters.

“We found a competition between the magnetic island and a nearby localized plasma current flow that can be described by the predator-prey model,” Kobayashi said, explaining that the model maps how the population of a predator is dependent on the population of its prey and vice versa. The relationship can be graphed as two overlapping lines rising and dipping just slightly out of sync. “The magnetic island is essential to reducing the plasma heat load, so the competitive oscillation between the magnetic island and the plasma current is also reflected in the plasma heat load on the diverter.”

The researchers used the predator-prey model between the magnetic island width and plasma parameters to describe the diverter oscillation and successfully reproduced the experimental observations. “Through this work, we significantly deepened the understanding of the background physics of the diverter detachment operation,” Kobayashi said. “Next, we plan to develop a stable and efficient detachment scenario, utilizing the background physics knowledge obtained through this work, to realize the magnetic plasma fusion plant.”

More information:

T. Kobayashi et al, Self-Sustained Divertor Oscillation Driven by Magnetic Island Dynamics in Torus Plasma, Physical Review Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.085001

Provided by

National Institutes of Natural Sciences

Citation:

Self-sustained diverter oscillation mechanism identified in fusion plasma experiment (2022, March 2)