A Dartmouth professor’s images of the explosive aftermath from the collision of two dying stars could help scientists better understand this rare type of astronomical event—and may finally confirm the identity of a brilliant but short-lived star observed nearly 850 years ago.

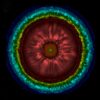

Robert Fesen, a professor of physics and astronomy, captured telescopic images that show a fireworks-like burst of thin filaments radiating from a highly unusual star at the center of an object called Pa 30, according to findings he announced Jan. 12 at the 241st Meeting of the American Astronomical Society. Fesen is lead author of a paper reporting the findings that has been submitted to the The Astrophysical Journal Letters for publication.

Pa 30 is a dense region of illuminated gas, dust and other matter known as a nebula. Fesen and his co-authors report that Pa 30 appears to contain little to no hydrogen and helium but is instead rich in the elements of sulfur and argon.

The nebula’s unusual structure and characteristics match the predicted result of a collision between end-stage stars known as white dwarfs, Fesen said. White dwarfs are faint, extremely dense stars about the size of Earth that contain the mass of the Sun. The merger of two white dwarfs is one proposed explanation for a subclass of supernovae—or star explosions—called Iax events, in which the star is not completely destroyed, Fesen said.

“I have never seen any object—and certainly no supernova remnant in the Milky Way galaxy—that looks quite like this, and neither have any of my colleagues,” Fesen said. “This remnant will allow astronomers to study a particularly interesting type of supernova that up to now they could only investigate from theoretical models and examples in distant galaxies.”

The size of Pa 30 and the speed at which it is expanding—about 2.4 million miles per hour—suggest the explosive collision occurred around the year 1181, the researchers report. That coincides with observations by Chinese and Japanese astronomers at the time of a very bright star that suddenly appeared in the constellation Cassiopeia and was visible for about six months as it slowly faded. These fleeting stars are known as “guest stars.”

The images Fesen captured of the nebula’s structure and luminosity not only provide the most accurate estimate yet of its age, but also could allow astronomers to refine existing models of white dwarf mergers. Pa 30 was discovered in 2013 by co-author and amateur astronomer Dana Patchick, but up until now, images of the nebula had shown only an extremely faint and diffuse object, Fesen said.

“Our deeper images show that Pa 30 is not only beautiful, but now that we can see the nebula’s true structure, we can investigate its chemical makeup and how the central star generated its remarkable appearance, then compare these properties to predictions from specific models of rare white dwarf mergers,” Fesen said.

Fesen took the images of Pa 30 in late 2022 using the 2.4-meter Hiltner Telescope at the MDM Observatory—which Dartmouth owns and operates with four other universities—adjacent to Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona. Fesen equipped the telescope with an optical filter sensitive to a particular emission line of sulfur. He captured Pa 30 in three 2,000-second exposures under very clear skies and took additional data on the nebula’s structure, size and velocity.

The study by Fesen and his co-authors built upon work published in 2019 by Russian researchers who found an extremely unusual star nearly in the dead center of Pa 30. That star exhibited several properties suggesting the collision of two white dwarfs, and it had a surface temperature of nearly 400,000 degrees Fahrenheit with an astounding outflowing wind velocity of about 35 million miles per hour.

In 2021, astronomers from the University of Hong Kong that had revisited the Russian team’s results reported that Pa 30 was roughly 1,000 years old and in nearly the same sky location as the guest star recorded in 1181. These researchers proposed that Pa 30 is the aftermath of a white dwarf collision that lit up the night sky nearly a millennium ago, though their margin of error on its age was 300 years.

“Our new observations put a much tighter constraint on the object as having an expansion age of around 850 years, which is perfect for it to be the remains of the 1181 guest star,” Fesen said. To the ancient astronomers, the new star would have been nearly as bright as, or brighter than, Vega, the fifth-brightest star in the sky as seen from Earth.

“The guest star was bright enough that three separate groups in China observed it within a couple of days of each other and it also was seen in Japan,” Fesen said. “A new star as bright as Vega would’ve been quite noticeable. To the ancients, their TV set was the sky, so they would’ve easily noticed and certainly recorded the sudden appearance of a bright new star in the heavens.”

Citation:

Images capture 850-year-old aftermath of stellar collision (2023, January 13)