The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

A new type of material can learn and improve its ability to deal with unexpected forces thanks to a unique lattice structure with connections of variable stiffness, as described in a new paper by my colleagues and me.

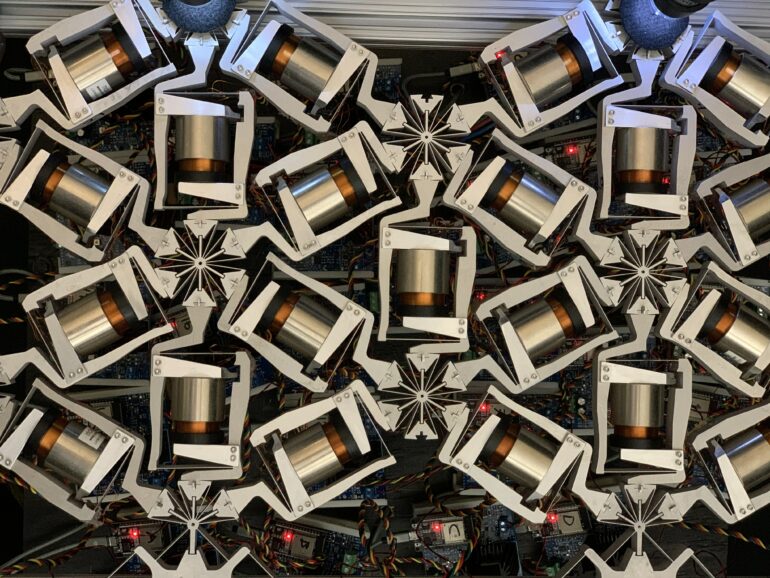

Architected materials – like this 3D lattice – get their properties not from what they are made out of, but from their structure.

Ryan Lee, CC BY-ND

The new material is a type of architected material, which gets its properties mainly from the geometry and specific traits of its design rather than what it is made out of. Take hook-and-loop fabric closures like Velcro, for example. It doesn’t matter whether it is made from cotton, plastic or any other substance. As long as one side is a fabric with stiff hooks and the other side has fluffy loops, the material will have the sticky properties of Velcro.

My colleagues and I based our new material’s architecture on that of an artificial neural network – layers of interconnected nodes that can learn to do tasks by changing how much importance, or weight, they place on each connection. We hypothesized that a mechanical lattice with physical nodes could be trained to take on certain mechanical properties by adjusting each connection’s rigidity.

To find out if a mechanical lattice would be able to adopt and maintain new properties – like taking on a new shape or changing directional strength – we started off by building a computer model. We then selected a desired shape for the material as well as input forces and had a computer algorithm tune the tensions of the connections so that the input forces would produce the desired shape. We did this training on 200 different lattice structures and found that a triangular lattice was best at achieving all of the shapes we tested.

Once the many connections are tuned to achieve a set of tasks, the material will continue to react in the desired way. The training is – in a sense – remembered in the structure of the material itself.

We then built a physical prototype lattice with adjustable electromechanical springs arranged in a triangular lattice. The prototype is made of 6-inch connections and is about 2 feet long by 1½ feet wide. And it worked. When the lattice and algorithm worked together, the material was able to learn and change shape in particular ways when subjected to different forces. We call this new material a mechanical neural network.

The prototype is 2D, but a 3D version of this material could have many uses.

Jonathan Hopkins, CC BY-ND

Why it matters

Besides some living tissues, very few materials can learn to be better at dealing with unanticipated loads. Imagine a plane wing that suddenly catches a gust of wind and is forced in an unanticipated direction. The wing can’t change its design to be stronger in that direction.

The prototype…