The practice of medicine has undergone an incredible, albeit incomplete, transformation over the past 50 years, moving steadily from a field informed primarily by expert opinion and the anecdotal experience of individual clinicians toward a formal scientific discipline.

The advent of evidence-based medicine meant clinicians identified the most effective treatment options for their patients based on quality evaluations of the latest research. Now, precision medicine is enabling providers to use a patient’s individual genetic, environmental and clinical information to further personalize their care.

The potential benefits of precision medicine also come with new challenges. Importantly, the amount and complexity of data available for each patient is rapidly increasing. How will clinicians figure out which data is useful for a particular patient? What is the most effective way to interpret the data in order to select the best treatment?

These are precisely the challenges that computer scientists like me are working to address. Collaborating with experts in genetics, medicine and environmental science, my colleagues and I develop computer-based systems, often using artificial intelligence, to help clinicians integrate a wide range of complex patient data to make the best care decisions.

The rise of evidence-based medicine

As recently as the 1970s, clinical decisions were primarily based on expert opinion, anecdotal experience and theories of disease mechanisms that were frequently unsupported by empirical research. Around that time, a few pioneering researchers argued that clinical decision-making should be grounded in the best available evidence. By the 1990s, the term evidence-based medicine was introduced to describe the discipline of integrating research with clinical expertise when making decisions about patient care.

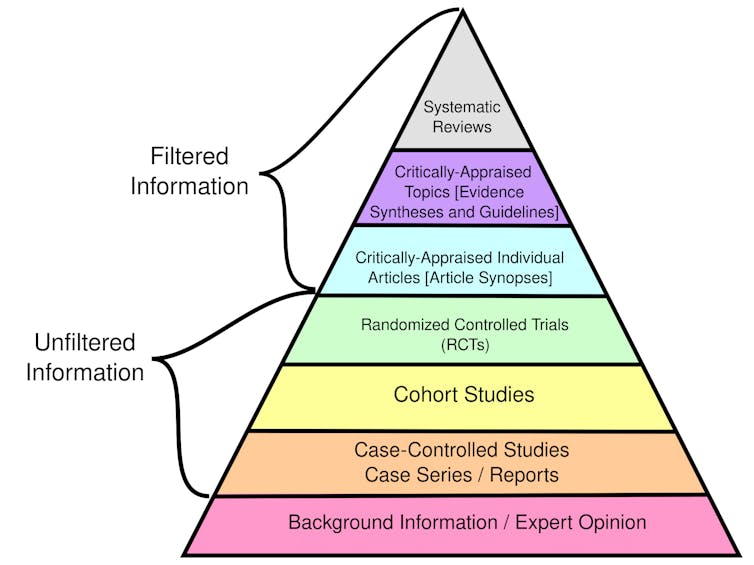

The bedrock of evidence-based medicine is a hierarchy of evidence quality that determines what kinds of information clinicians should rely on most heavily to make treatment decisions.

Certain types of evidence are stronger than others. While filtered information has been evaluated for rigor and quality, unfiltered information has not.

CFCF/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Randomized controlled trials randomly place participants in different groups that receive either an experimental treatment or a placebo. These studies, also called clinical trials, are considered the best individual sources of evidence because they allow researchers to compare treatment effectiveness with minimal bias by ensuring the groups are similar.

Observational studies, such as cohort and case-control studies, focus on the health outcomes of a group of participants without any intervention from the researchers. While used in evidence-based medicine, these studies are considered weaker than clinical trials because they don’t control for potential confounding factors and biases.

Overall, systematic…